The percussive thump and burr which sparked into life Francesco Provenzale’s ‘Non posso far’ (from his opera Lo Schiavo di sua moglie) at the start of this lunchtime recital by Thomas Dunford’s Jupiter ensemble and French-Italian mezzo-soprano Lea Desandre may not have been quite what the audience at Wigmore Hall was expecting, but it was a fitting opening gambit for this programme devoted to Amazonian Queens, at war and in love.

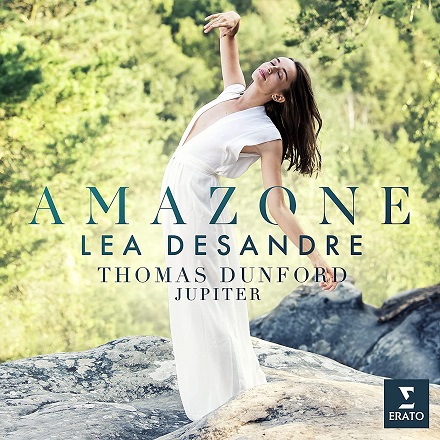

The recital comprised repertoire from Desandre’s first solo disc, Amazone, which, released on the Warner Classics label in 2021, presents a programme, curated by musicologist Yannis François, of Baroque arias from France, Italy and Germany – one which surprisingly reveals the myth of the Amazons to have been ripe subject matter for Baroque opera composers. It’s intriguing to reflect upon the political and cultural meanings that may have been conveyed by the Amazonian theme, but at Wigmore Hall more immediate matters were at hand, as Desandre told the mythic Queens’ stories with wonderfully engaging character, diversity and persuasiveness. These most powerful women may have been raised to make war against men but, their independence of spirit notwithstanding, their wildness led them to make both war and love with passion. And, Desandre and Jupiter vividly dramatised the interactions of Theseus and Antiope, Hercules and Hippolyta, Thalestris and Alexander the Great, balancing aggression with ardour, conquests with grief.

Provenzale (1624-1704) was one of seventeenth-century Naples most representative musicians, working for virtually all of the important Neapolitan musical institutions. At the conservatories of S. Maria di Loreto and S. Maria della Pietà dei Turchini he trained a whole generations of musicians, helping to foster and maintain a Neapolitan tradition. Of six opera he is known to have written, only two scores are extant: for La Stellidaura vendicata (1674) and Lo schiavo di sua moglie (The Slave of his Wife). In the latter, three Greek warriors, Teseo, Ercole and Timante engage in a war against the Amazons but fall under the spell of the Amazon queen, Ippolita, and her sister Melanippa.

In ‘Non posso far’, Desandre laughed with melismatic relish to see the warriors ditch their skirts and take up arms, leaving their male counterparts floundering both on and off the battlefield. But, the Amazons don’t get it all their own way and ‘Lasciatemi morir’ was an affecting plea by the captured Menalippa for the stars (“stelle crudeli”) to let death consume her. The bright vivacity of the first aria gave way to darker, though no less, vivid, hues in the second, a Sinfonia from Francesco Cavalli’s Ercole amante forming a sombre transition between the two, as the violinists gently caressed their strings, and texture and timbre deepened. Desandre affectingly made one feel the veracity of Menalippa’s plaint that “L’armi non sono mai, Non solo mai d’amor fidele” (Weapons are never true expressions of love).

Giovanni Buonaventura Viviani (1638-1693) began his career as a violinist at the court of Innsbruck but later worked in various Italian cities, including Venice, Rome and Naples. The impresario of the latter’s Teatro dei Fiorentini called Viviani to the city in October 1681 and his opera Mitilene, regina delle Amazoni was performed in the royal palace in November, before transferring to the theatre. Scholar Andrea Garavaglia has shown that the libretto, by the Milanese count Teodoro Barbo, was an elaboration of an earlier libretto, La simpatia nell’odio, overo Le amazoni amanti by Giovanni Pietro Monesio (1664), which was itself a translation of the Spanish play Las Amazonas by Antonio de Solı´s (1657), the play also being the basis of Caduta del regno delle Amazzoni by Domenico De Totis (1690), which was set by Bernardo Pasquini.[1] Such cultural exchanges and conduits are fascinating; Giuseppe de Bottis (1678-1753) also set Barbo’s libretto and his opera was staged in Naples in 1707. Later in the programme, ‘Lieti Fiori’ from the latter allowed Desandre to display the beautiful brightness and clarity of her mezzo, which frequently acquires soprano-like tints. The upper strings’ delicate fade out at close seemed to fulfil the protagonist’s wish that blessed flowers will “relieve the great passion in my heart” (“Del mio seno mitigate il grande ardore”).

Jupiter gave us ‘Muove il piè, furia d’Averno’ from Viviani’s Mitilene, the advance of the fury of Avernus – a volcano near Naples which was thought to be the gateway to hell – triggered by Dunford’s vigorous strum and dramatised by the strings’ dynamism and colour. Desandre released a fittingly fiery flash at the close, “Ho do Cerbero il veleno” (I have the venom of Cerberus coursing). There were more storms inthe ‘Sinfonia pour la tempête’ from Die getreue Alceste by Georg Caspar Schürmann (1672-1751), as the percussionist (unnamed in the programme) unleashed tempestuous thunder that, with the lute’s furious thrumming, fuelled the violins’ Zephyrs – there was a lot of air between the flying bows and strings!

Schürmann began his career in Hamburg, as a male alto, but was later appointed to the court of Duke Anton Ulrich of Brunswick-Lüneburg, where he produced over thirty operas. Die getreue Alceste was first performed in Brunswick in February 1719, but the fruits of Schürmann’s sojourn in Venice in 1701 are felt in the revised version that he made in July 1719 of that year for the Gansemarkt-Theater in Hamburg, for which he added 15 Italian arias. Desandre handled the roulades of ‘Non ha fortuna il pianto mio’ ease, displaying fluency, agility, and a wide range of both tessitura and colour to convey the distress of Hyppolite as she pines for her love, Hercules.

Dividing his time between Venice and Dresden, Carlo Pallavicino (c.1640-1688) produced more than twenty operas. When he died on 29th January 1688, the score of his twenty-third opera, Antiope, to a libretto by his son, was unfinished and Nicolaus Adam Strungk completed the two arias that we heard here. The opera tells of the clash between the Amazons and the Greeks which saw Theseus take Queen Antiope back to Athens as his bride. ‘Vieni, corri, volami in braccio’ had a lovely lilt, as Desandre smoothed through the lines cleanly, with impressive control and with a beguiling freedom in the voice. She climbed expressively to the top at the close, capturing the bittersweetness of a heart gloriously ‘wounded’ by blind Cupid’s arrow. In contrast, ‘Sdegni, furori barbari’ burned richly and raced agilely, powered by jealousy – and by the ferocious bite of the accompaniment – culminating in a vicious cry of wrath: “D’ire ministra sia.”

An energised rendition of the recitative ‘Venez, troupe guerrière’ from Les amazones by Anne Danican Philidor (1681-1728), in which Hippolyte and Thalestris galvanise their warrior band, was followed by ‘L’Américaine’ from Marin Marais’s Suite d’un goût étranger. Dunford was characteristically mischievous here, his improvisatory fingers tickling the strings with fairy dust, then unleashing a warm, vigorous strum as the tuneful dance unfolded. Somehow he makes the music feel ‘three-dimensional’, the relationship between the high and low strings carving a sonic space. Teasing pauses and rubatos, and subtle ‘tripping-up’ of the rhythmic regularity, kept the lower strings on their toes – as the violinists grinned from side of the platform.

André Cardinal Destouches (1672-1749) had a varied career. He started life destined for the Church, but in 1692 joined the second company of the ‘Mousquetaires du Roi’, then changed tack again in 1712, when he became ‘Surintendant de la musique du roi, et inspecteur-général de l’Opéra’. In ‘Ô Mort! Ô triste mort’ from Marthésie, reine des Amazones, the strings seemed almost to ‘squeeze out’ the protagonist’s sorrow as they plead for death to end their desolation.

The end of the recital offered fare from a more familiar name, Antonio Vivaldi. Three instrumental items from Ercole su’l Termodonte, including a plaintive Andante in which the restrained strings were complemented by elaborations from the lute and harpsichord, interweaved between the arias from de Bottis and Schürmann, and led to Vivaldi’s ‘Onde chiare che sussurate’, in which whispering ripples and murmuring streams console Hippolita’s yearning. Desandre and Jupiter saved their best till last: the mezzo-soprano made the rapturous vocal line meltingly beautiful, her control and composure absolute and transfixing, while violinists Louise Ayrton and Augusta McKay Lodge made nature’s sounds float with tender délicatesse.

This recital is available on BBC Sounds until the end of February.

Claire Seymour

Amazone: Lea Desandre (mezzo-soprano), Jupiter Ensemble: Thomas Dunford (lute), Louise Ayrton (violin), Augusta McKay Lodge (violin), Jasper Snow (viola), Salomé Gasselin (viola da gamba), Arthur Cambreling (cello), Hugo Abraham (double bass), Violaine Cochard harpsichord (organ)

Francesco Provenzale – ‘Non posso far’ (Lo schiavo di sua moglie); Francesco Cavalli – Sinfonia (Ercole amante); Provenzale – ‘Lasciatemi morir’(Lo schiavo di sua moglie); Giovanni Buonaventura Viviani – ‘Muove il piè, furia d’Averno’ (Mitilene, regina delle Amazoni); Georg Caspar Schürmann – Sinfonia pour la tempête (Die getreue Alceste); Carlo Pallavicino – ‘Vieni, corri, volami in braccio’ (completed by Nicolaus Adam Strungk), ‘Sdegni, furori barbari’ (completed by Nicolaus Adam Strungk)(Antiope); Anne Danican Philidor – ‘Venez, troupe guerrière’ (Les amazones); Marin Marais – ‘L’Américaine’ (Suite d’un goût étranger); André Cardinal Destouches – ‘Ô Mort! Ô triste mort’ (Marthésie, reine des Amazones); Antonio Vivaldi – Overture: I. Allegro (Ercole su’l Termodonte RV710); Georg Caspar Schürmann – ‘Non ha fortuna il pianto mio’ (Die getreue Alceste); Antonio Vivaldi – Overture: II. Andante (Ercole su’l Termodonte RV710); Giuseppe de Bottis – ‘Lieti fiori’ (Mitilene, regina delle Amazzoni); Antonio Vivaldi – Overture: III. Allegro, ‘Onde chiare che sussurate’ (Ercole su’l Termodonte RV710)

Wigmore Hall, London; Monday 30th January 2023.

[1] Garavaglia, A. and Kamal, K. (2012) ‘Amazons from Madrid to Vienna, by way of Italy: the circulation of a Spanish text and the definition of an imaginary’, Early Music History, 31: 189–233.