The fifth opera of the lengthy Richard Strauss canon, The Woman Without a Shadow (1915) is surely the richest work of them all, traversing real and imaginary worlds while proving its actors worthy to receive the fruits of love. Just now in San Francisco it was the David Hockney production, first seen 30 years ago at Covent Garden and L.A. Opera.

Die Frau Ohne Schatten is no stranger to San Francisco, the opera marking its American premiere at the War Memorial Opera House in 1959 in a production by the then 27 year-old Jean-Pierre Ponnelle. This gifted designer/director quickly became the avant-garde star of the then progressive San Francisco Opera.

The opera returned in 1976 in a production by Nikolaus Leinhoff from the Stockholm Opera designed by Jorg Zimmermann, its 1980 San Francisco revival notable for Brigit Nilsson’s Dyer’s Wife. James King sang the Emperor with Leonie Rysanek as the Empress..

The challenges of mounting Die Frau Ohne Schatten are daunting, not only the casting of five heroically voiced singers, making space for a Strauss orchestra of nearly a hundred players, finding places for big off-stage choruses and backstage banda instruments, but also for the instantaneous, back and forth transformations of the stage from the poor dyer’s hut of a Scandinavian fairytale to the magical landscapes of a medieval Indian sultan.

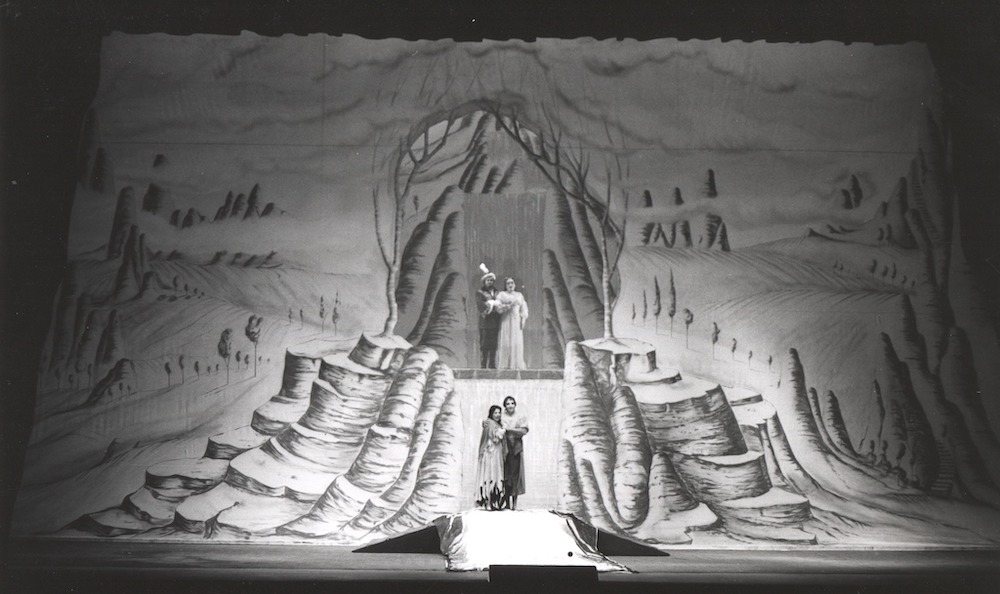

The David Hockney 1992 production finds a balance between these worlds, as well as merges the Mozartian and Wagnerian thematics that co-exist in the libretto, all this within the hyper post-Romanticism of the Strauss score. No small feat.

Hockney’s operatic world is filled with brilliant color (his The Rake’s Progress is an explicable exception, i.e. it is Stravinsky’s dry neo-classicism). Like Messiaen and Scriabin Hockney was born with synesthesia — seeing color is his response to music. To this add the modeled linear flow of musical line, and the Hockney obsessive manipulation of perspective. Die Frau ohne Schatten was destined to become a part of the Hockney operatic oeuvre, joining The Magic Flute, Tristan and Isolde, and Turandot, all works of enormous musical color and fantastical content.

San Francisco Opera expanded its pit in 1976 to accommodate enlarged 19th and 20th century orchestras, and specifically at that moment to entice legendary conductor Karl Böhm to conduct Die Frau ohne Schatten. In more recent times, with the institution of a music directorship (lacking during the Kurt Herbert Adler years), the San Francisco Opera Orchestra has developed into one of the world’s fine opera orchestras. Plus current opera house practices have increased the number of orchestra rehearsals, priming the pit just now for this superlative collaboration with the famed visual artist.

Former music director Donald Runnicles returned to San Francisco Opera for this production, as he has for the two recent Wagner Ring cycles. Mo. Runnicles’ musical identity is rooted in the huge Romantic and post-Romantic repertory, thus he mined all possible richness and volume from the Strauss score, reveling in its myriad musical colors. It is a huge orchestra playing big music about what, one is not sure.

Surely it is about more than the dyer and his wife discovering that their humble love will transform into children who will then discover in turn that love will, in principle, prevail eternally. All this while Europe is sitting on a powder keg waiting for the spark that did indeed soon strike. Die Frau ohne Schatten seems to hold all this explosive geopolitical might within its massive dramatic tensions. They would not explode if only the Nurse in the opera had her way — that the shadow of the Dyer’s wife would be stolen so that the emperor would not be turned to stone.

So maybe Die Frau ohne Schatten is simply about making art, not war.

San Francisco Opera has given to art its all, assembling a cast whose voices could be well heard through the orchestral forces.

Famed Swedish soprano Nina Stemme was the dyer’s wife whose shadow was not stolen after all (see lead photo). Mme. Stemme, now sixty years old, is in fine voice, well able to sustain her beautiful, powerful high tones, if without all the brilliant luster of her 2011 San Francisco Brünnhildes. Importantly Mme. Stemme did actually project a sense of character adding a real humanity to the role, while never sacrificing its heroic vocalism. A greater warmth of tone in her mid voice would have enriched her reconciliation with Barak, her husband.

The dyer Barak was sung by Danish bass-baritone Johan Reuter. He too projected the humanity of his role, providing the warmth of character that librettist von Hofmannstahl and Strauss sought, winning our sympathy by sparing his donkey a weight of burden, and expressing his fear that he would not be able to feed his eventual children.

The Emperor was sung by British tenor David Butt Philip whose voice is very beautiful indeed. His second act visit to the falcon house (his falcon had wounded a gazelle who then turned into a woman — the Empress) was the most beautifully sung, indeed truly magical scene of the performance. The role lies high, and the vocal lines are extended making it a virtuoso display, achieved with consummate ease by Mr. Philip.

The Empress was sung by Finnish soprano Camilla Nyland whose voice is of a beautiful, silvery tone that brilliantly negotiated the lengthy, high tessatura of the role. It is a voice that, with Mr. Philip’s Emperor, could take us into the magical, loftier world of pure beauty, but only if she could find a shadow. The Empress effects the dénouement of the opera in the huge, fountain-of-life scene where she refuses to sacrifice the earthly love of the Dyer and his wife (and their eventual children) to gain her shadow, and the Emperor is thereby turned to stone. Mme. Nyland effected the scene without ascending vocally or dramatically to its potentially spiritual heights.

The Nurse was sung by American soprano Linda Watson who sings both Herodias at La Scala and Isolde in Dusseldorf. She combined both roles for this production, deftly driving the role’s machinations that seemed to be more motivated by pure evil rather than by love and protection for her mistress, the Empress. As well she fearlessly drove an oarless boat to the temple in India or somewhere where she was then soundly dismissed by her mistress.

All this magnificence found its way onto the War Memorial Opera House stage with the deft guidance of stage director Roy Rallo, with the very able assistance of lighting designer Justin A. Partier, both men bringing vibrant new life to the Hockney production.

Michael Milenski

War Memorial Opera House, June 10, 2023. All photos courtesy of San Francisco Opera, photos of the Hockney production are copyright Cory Weaver.