In 1954-57 Bohuslav Martinů composed The Greek Passion, an opera about Greek refugees seeking a bit of land in a nearby (likewise Greek) village where they might work and live, and about the hard-heartedness of the comfortable and settled villagers, hesitant—and finally refusing—to help them. The refugees are homeless because the Turkish troops have just destroyed their village and chased them off their land. (The action takes place during the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-22.) Individuals from the village begin to interact with the refugees: some help, others seek a way to defraud them or to drive them away.

The shepherd Manolios has been cast as Christ in the upcoming passion play, and he identifies more and more with the role as the opera goes on. He boldly speaks up for the wanderers, reminding his fellow villagers of Christ’s message to protect the defenseless. Panait, who has been cast as Judas in the play, denounces Manolios. I n the end, Manolios is murdered for having urged that the refugees be welcomed and aided.

Some sixty years later, the opera seems as timely as ever.

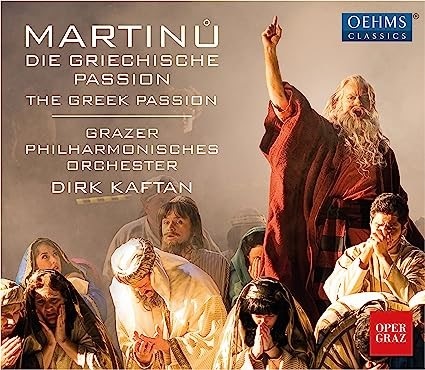

This lively and skillful recording was made during a series of staged performances from March and April 2016 in Graz, a major city in southeastern Austria (not far from the border with Slovenia).

Martinů’s opera had a complex history. He composed it to his own libretto, which he based on an English translation of Nikos Kazantzakis’s widely read 1954 novel; the various editions of the translation carried one of two titles: Christ Recrucified or The Greek Passion.

Martinů set the text in English, having been encouraged by the Royal Opera House in London (Covent Garden), but the opera, once completed, was rejected by the Covent Garden board. He then tightened and heavily recomposed it. The result is, in a way, two different operas that share some musical material. The premiere of the rewritten version was given in 1961, in Zurich, and has been recorded several times, in English and in Czech translation.

The semi-forgotten London version belatedly received its premiere in 1999, in Bregenz (in western Austria, near Switzerland). It is more sprawling than the second (Zurich) version but also in many ways more imaginative, not least in using a large amount of spoken dialogue (including several purely spoken roles) and even some spoken passages for the chorus.

The present recording adopts the original (London) version. It is extremely effective. The many, diverse characters in the story come to life as one listens, and the frequent passages for chorus give a powerful sense of the plight of the refugees.

The singers come from a number of countries: the Manolios is Swiss, the Katerina is Ukrainian, and so on. Singers in some smaller roles come from Greece, Turkey, and China. All generally sing well, though some have a touch of the all-too-familiar opera-house wobble. A notable exception is the lovely lyric soprano who sings the young Despinio (Sofia Mara, from Uruguay); alas, the character collapses and dies onstage early in the opera.

Martinů’s musical style in this first version of The Greek Passion is, as in so much of his work, tonal yet inventive. At moments, I felt that I was listening to a work by Copland. The many orchestral preludes, interludes, and postludes are particularly colorful. The solo lines vary widely, from near-psalmodic recitation to moments of Puccinian grandeur. The choral writing is likewise imaginative throughout, as for example in those moments of choral speaking.

Some of the singers pronounce the English text rather well, others opaquely or misleadingly (e.g., “sheep” becomes “ship”). Best is the crucial scene in which Ladas (a purely spoken role) tempts the easily duped Yannakos into helping him trick the refugees—and bribes him with three gold coins. (Yannakos’s role in the upcoming Passion Play is of course Peter.)

Still, even in the many sung passages, I could catch about half of the text by ear, and the rest was made clear by following along in the booklet. A few of the spoken lines, as recorded, differ somewhat—or in one case heavily—from what is printed in the booklet. The changes all help make matters clearer, so I am totally in favor.

The orchestral and choral contributions are firmly realized under Dirk Kaftan, who has been music director of the Graz Opera since 2013. The recorded sound is well balanced and full, with enchanting offstage effects. One can readily imagine oneself at a performance.

I believe that the only previous recording of the original (London) version was the one on Koch from the 1999 Bregenz premiere, featuring Christopher Ventris and a young Nina Stemme. Michael Mark, reviewing it in American Record Guide, reported that the singers, though with voices that are mostly not “opulent,” nonetheless “command attention because of their musicality and fervent identification with their roles.” Still, he concluded that Mackerras’s 1981 recording was “clearly preferable.” Mackerras’s recording has recently been re-released by Supraphon. But of course it uses the greatly reworked second (Zurich) version and thus is not really comparable.

In any case, the Bregenz recording of the first version is no longer available. (A video of the production is available online, but without subtitles to help one figure out the English words that are being sung: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vEJQLy0imM.) Thus the new Graz recording becomes the best way to get a sense of what the fascinating first version of Martinů’s opera has to offer. That is, until a recording finally comes along with a first-rate cast of singers—preferably with, yes, opulent voices—who can put an English text across vividly and naturally.

Michael Haas (in an online essay, with some intriguing sound-files) has urged attention to another interesting and, again, timely opera about refugees: Fremde Erde (Alien Soil; 1929-30), by Karol Rathaus (https://forbiddenmusic.org/2016/05/04/fremde-erde-prescience-as-opera/). Is any record company out there interested in letting us hear that forgotten but, I suspect, very stage-worthy work?

Ralph P. Locke

Bohuslav Martinů: The Greek Passion

Dshamilja Kaiser (Katerina), Tatjana Miyus (Lenio), Taylan Reinhard (Panait), Rolf Romei (Manolios), Manuel von Senden (Yannakos), Wilfried Zelinka (Priest Grigoris), Markus Butter (Fotis, Priest of the Refugees); Dirk Kaftan (conductor), Graz Philharmonic, Choruses of Graz Opera and Graz University of the Arts.

Oehms OC 967 [2 CDs] [137 mins]