In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the aesthetic and songs of courtly love travelled to Germany from Provence and northern France. Minnesinger, like their Romance counterparts, composed both the texts and music of their songs, which were performed in public at the courts on whose patronage they depended for their livelihoods. Some of the early Minnesang texts were probably sung to melodies by the Provencal and Occitan troubadours and the northern trouvères (or adaptations of such melodies), although the German songs did have distinct characteristics, often being pentatonic, and sometimes incorporating elements of popular song and Gregorian chant.

Walther von der Vogelweide (c.1168-c.1230) was one of the greatest lyric poets of the German Middle Ages. His place of birth is unknown, though some speculate that he may have been born near the monastery of St. Gallen where there were many master minnesingers. He was a wandering minstrel, travelling on horseback between princely courts – as he says: ‘Von der Elbe bis zu Rhein,/ Und bis in das Ungarland hinein,/ Von der Seine bis zur Mur,/ Vom Po bis an die Trave.’ (From the Elbe to the Rhine, and right into Hungary, from the Seine to the Mur, from the Po to the Trave.)

His first patron was Frederick I, also known as Frederick the Catholic, who was the Duke of Austria from 1195 to 1198. After Frederick’s death, strife ensued regarding the rival claims to the succession of Philip of Swabia and Otto of Brunswick. A little more than half of the 200 or so of Walther’s extant poems extend the conventions of the courtly love lyric (Minne) to embrace matters social, political and religious (Sprüche), and in songs composed at this time Walther laments the civil unrest and deterioration of courtly manners and morals. In 1204 we find him at the court of Hermann I, Landgrave of Thüringen, where he participated in 1207 in the famous Sangerkrieg at Wartburg, which inspired Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. (Wagner’s Tannhäuser is also based on minnesinger art and tradition.) After that, there is evidence that he travelled between Vienna, ruled by Leopold VII, and Meissen, also returning to Thüringen, to Otto’s court, and joining the court of Frederick, son of Henry VI. It is Frederick whom Walther addresses in songs from this time in which, weary of his wandering life, he longs for a home of his own.

The Minnesang texts are preserved in collections such as the Codex Manesse, which was compiled between c.1304-40 and is the single most comprehensive source of Middle High German Minnesang poetry (and the main source for Walther’s works). This beautifully illumined manuscript also contains miniature portraits depicting the minnesingers. In the portrait of Walther, the armorial bearings suggest that he was a knight, though despite his noble birth he was still dependent on his art for his bread. The device on his shield relates to ‘Vogelweide’, which refers to fields in which singing birds, and hawks for hunting, were captured.

Musical sources of Minnesang, however, are rare. The ‘Palästinalied’, probably written at the time of the Fifth Crusade (1217-21) and contained in the Münster Fragment (c.1330), is the only complete and reliable melodic transcription of a song by Walther (it has been suggested that it is itself a contrafact of a melody, ‘Lanquan li jorn son lonc en mai’ by the trouvère Jaufré Rudel (c.1100-c.1147)). So, anyone who wants to perform Walther’s songs is going to come up against a seemingly insuperable brick wall. What to do? It’s a question that musicologist Professor Marc Lewon answers in his fascinating account of the analysis of various extant sources – a veritable science of deduction – that has enabled him to recreate, re-imagine and re-compose the music of Walther von der Vogelweide that is performed by Joel Frederiksen and the Ensemble Phoenix Munich on this deutsche harmonia mundi release.

Lewon explains that the first step for the musical detective is probably to search for songs by the French trouvères and Occitan troubadours that might have served as models for rewriting (contrafacts) by German minnesingers. For example, ‘Under der linden’ is considered to be a contrafact over the anonymous ‘En mai en douz tens nouvel’, and the melody of the latter can be adapted to fit Walther’s text. As well as looking ‘sideways’, one can also look forwards, to the 16th and 17th centuries when the Meistersingers held Walther in high esteem and adapted – according to contemporary tastes – melodies that had been handed down, over 400 years, under his name. Lewon describes the ‘reverse engineering’ that can bring these melodies back within the fold of thirteenth-century aesthetics. So, in ‘Mir hât Gêrhart Atze ein pfert’, a variant found in the Singebuch (1588) of Adam Puschmann of a melody attributed (under the title ‘Kreutzon’) to Walther by the Meistersingers has been adapted to Walther’s text.

Then, there are some fragments of musical notation (adiastematic neumes) which are no longer clearly decipherable, but which can provide a starting point for reconstruction. The Codex Burana (c.1225/30), for example, contains two strophes by Walther: Lewon explains how, informed by knowledge of common stylistic elements in the existing Minnesang melodies, one can use the rough information about the number and course of notes offered by the staff-less neumes to compose a melody which contains some elements of Walther’s style.

Moreover, though the texts of the Codex Burana are Middle High German and Latin, the manuscript crosses Europe’s geographical and linguistic boundaries. Thus, Lewon describes how, in the Codex, one of the two stanzas of Walther’s ‘Muget ir schowen’ which are attached to Latin poems is provided with staff-less neumes (suggesting that the scribes had produced a contrafact); but, more than this, the neumes can be matched with ‘Quant je voi l’erbe menue’ by the trouvère, Gautier d’Espinau, long assumed to be the model for Walther’s song. So, Gautier’s melody can be adapted to Walther’s text, with the aid of the Codex Burana’s neumes. And, to this Lewon has added two more voices, drawing on the style of the Parisian Notre Dame school, texts and music from which are also found in the Codex. On the disc, the resulting ‘Hebet sydus’ is performed alongside Gautier’s and Walther’s songs.

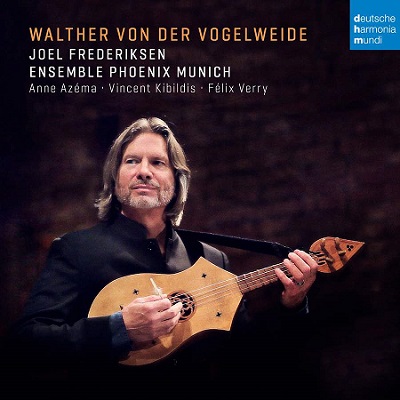

Lewon’s account of his unravelling of the intricate intertextual spiders’-webs and palimpsests – a task that clearly has required both meticulous scholarship and imaginative re-creativity – is utterly absorbing, and the ravishing songs that Ensemble Phoenix Munich perform on this disc are no less so. The instruments played – citole, a forerunner of the cittern (Frederiksen); harp (Vincent Kibildis); fiddle (Félix Verry) – are based on the visual art of the period, since it’s not certain what instruments the minnesingers would have played to accompany themselves.

A purposeful optimism infuses the instrumental opening of ‘Palästinalied’, and Joel Frederiksen sings with authentic joy, as the crusader lays eyes on the Holy Land for the first time:

For the very first I am alive to myself,

since my sinful eye beholds

the noble land, and also that earth

to which so much honour is given.

That has come to pass for which I have

always prayed: I have come to the place

where God walked in human form.

The need expressed here to actively engage in pilgrimage makes one wonder whether Walther was involved in the Third Crusade (1189–1192), fighting in the army of Leopold V of Austria, the helmet and sword in the miniature in the Codex Manesse suggesting that he has been knighted for military service.

Frederiksen’s bass is wonderfully rich and vivid. There are some telling rubatos at the ends of phrases which convey the crusader’s wonder and spiritual fulfilment – Palestine far exceeds the fair lands he has seen elsewhere. And, instrumental commentaries enhance the sense of awe. Expressive rhetoric force emphasises his ethical commitment to religious militarism: “Otherwise we would be lost, If it weren’t for the spear, the cross and thorn./ Woe to you, heathen, for this outrage to you!” The instrumental textures are varied to delineate the discrete sentiments of the stanzas; in the penultimate stanza, for example, the reference to the Day of Judgement initiates a sparseness, the delicacy of which suggests both fear and redemption. Allied with Frederiksen’s delivery, which eschews a sense of classical ‘schooling’ and is powerfully direct, such gestures transport the listener back to those medieval courts: one can imagine Frederiksen catching a prince’s eye, holding a knight in his gaze. The final line, “we are pursuing a just claim,/ so it is fair that He grant it.”, is spoken with sincerity. The immediacy is quite magical.

‘Palästinalied’ is preceded by the French soprano Anne Azéma’s unaccompanied rendition of Rudel’s ‘Lanquan li jorn son lonc en mai’, a song thought to have been composed during the preparation for the Second Crusade which, with its refrain of amor de loing (‘love from afar’) – the paradox of love generated by distance – and evocations of the Saracens’ kingdom, takes a different perspective on the chasm between the Islamic East and the Christian West. Azéma clearly has this music – and its contradictions – in her blood. Her tone is inspiringly pure and her phrasing exquisite: the silences at the end of phrases seem as important as the preceding arcs and curlicues. Her enunciation of the courtly French has a lovely edge, matched by her vocal timbre when she deepens the expressive nuances and when the melismatic, slightly oriental, wriggles take hold of the melodic line. I love the way she injects a heat into the fusion of religious and erotic love: “Oh! I wish I were a pilgrim there,/ my staff and my cloak/ reflected in her beautiful eyes.” The emotional intensification of the stanzas is brilliantly controlled, leading to a final verse in which a sensuous gentleness invites us to share the poet-singer’s ecstasy: “I shall have no pleasure in love/ if it is not the please of this far away love.”

The Münster Fragment which contains ‘Palästinalied’, also preserves the musical notation of the end of Walther’s ‘König-Friedrichston’, in which the poet requests his own hearth: “Oh, how I would then sing of the little birds/ And of the heath and of the flowers,/ as I once sang!” This music would also have begun the song, so, Lewon has only had to recompose the central part of the song. Frederiksen’s unaccompanied bass dives deep, in register and in realism; no wonder King Frederick’s heartstrings were tugged.

There are also examples of Walther’s possible contrafacta. The anonymous ‘En mai en douz tens nouvel’ is adapted to Walther’s ‘Under der Linden’, and while we may not be certain how, or if, these chansons were accompanied, Vincent Kibildis’s harp caresses, pierces, decorates and echoes Azéma’s vocal line in ways which makes one find joy in the musical freedom that such ambivalence offers. The subtleties that Azéma brings to her natural affectation of a folk style are again astonishing. When she sings of how her beloved “kissed me a thousand times!”, so crisp is the text, so light the voice, that she seems to be standing on tiptoe to reach up to those kisses. Then, as Kibildis lets his harp celebrate such joy, there’s a rough ripeness in the salutation of love, “see how red my mouth is”, and, later, a knowing intimacy that the tandaradei (nightingales) who have been watching “will not say a word”.

‘Vil wunder wol gemachet wîp’ is one of the longest of Walther’s texts; Codex 127 of the Kremsmünster Abbey Library contains, alongside the text, one line of neumes, and Lewon has brought his familiarity with the idiom to bear in filling in the gaps. Wonderfully expressive fiddle-playing by Verry is delicately enriched by the harp to capture the inseparability of sorrow, beauty and love that Frederiksen’s vocal line expresses, as the poet-singer extols his beloved’s physical beauty and moral perfection. At times, the song’s unusually melismatic flights encourage Frederiksen to let his bass free, but the balancing of courtly decorum and intense passion creates an astonishing aural frisson. The Songs of Solomon have nothing on this.

The song is followed by an Estampie (a dance with repeated sections) which develops the vocal material. Similarly, one of Walther’s most famous texts, ‘Ich saz üf einem steine’ – which he is singing to himself in the Codex Manesse illustration above, and which is presented here through an adaptation of ‘Lange Ton’ from the Meistersingers tradition (again drawn from Puschmann’s songbook) – is preceded by Kibildis’s improvisatory and spirited, sometimes surprisingly festive, elsewhere poignantly poetic, instrumental response to the vocal line into which it segues.

‘Ich hân mîn lêhen’ expresses Walther’s delight in Frederick’s bestowal of a ‘fief’: “I have my fief!/ I need not fear the frosts of February/ upon my feet and won’t have to beg to/ all those stingy masters anu more.” Frederiksen makes one feel the shiver of that frost, the warmth of the patron’s generosity, the paucity of poverty and the self-awareness that the latter can bring a coarseness that has now been overcome – all in the space of two minutes.

The disc concludes with ‘Frô Welt, ir sult dem write sagen’, a parting from the World in which, over a drone, Azéma (Madam World) beseeches the poet-singer to stay with her a while longer. But, Walther weans himself away. The German lyric master was buried in the grounds of the Cathedral at Würzburg. A legend, memorialised by Longfellow, goes that he left his estate to the monks with the stipulation that they should feed the birds on his tomb:

Saying, “From these wandering minstrels

I have learned the art of song;

Let me now repay the lessons

They have taught so well and long.”

Lewon tentatively suggests that the path to the performance of Walther’s melodies is a rocky one. But, Frederiksen describes the whole process as ‘performance art’ – the performances, however speculative, bring the texts to life.

Claire Seymour

Joel Frederiksen (bass, citone), Anne Azéma (soprano), Vincent Kibildis (harp), Félix Verry (fiddle)

Walther von der Vogelweide: Zuo Rôme voget, zuo Pülle künic (completed by Marc Lewon), Under der linden, Vil wunder wol gemachet wîp (completed by Marc Lewon), Vil wunder wol gemachet wîp – Estampie, Mir hât her Gêrhart Atze ein pfert, Quant je voi l’erbe menue, Hebet sydus (arr. by Marc Lewon), Muget ir schowen, Ich saz ûf einem steine (instrumental), Ich saz ûf einem steine (arr. by Marc Lewon), Alte clamat Epicurus, Lanquan li jorn son lonc en mai, Nû alrêst leb ich mir werde, ‘Palästinalied’ (arr. by Marc Lewon), Ich hân mîn lêhen, Durchsüezet und geblüemet, Tannhäuser Stampedes, Frô Welt, ir sult dem wirte sagen

deutsche harmonia mundi 19658725032 [68:22]

ABOVE: The Funeral of Walther von der Vogelweide (c.1170–c.1230), the Minnesinger; Friederich Wilhem Ferdinand Theodor Albert (1822–1867), National Trust, Lanhydrock