During his tragically short life, Peter Warlock – the pen name used by Philip Heseltine (1894-1930) – composed around 119 solo songs, 23 choral works (some unaccompanied and others with keyboard, chamber or orchestral accompaniment), and several works for string orchestra, as well as a handful of works for piano. He also wrote a large number of critical reviews and magazine articles, and as a writer, editor and transcriber made a significant contribution to musical scholarship, especially in the field of Tudor and Jacobean music which he championed for years.

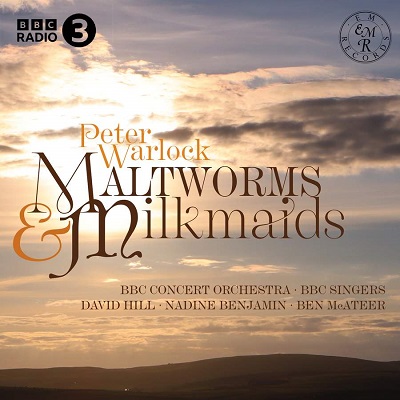

Apart from the charming and ever-popular Capriol Suite – an orchestral string arrangement of various dances from Arbeau’s 1588 treatise on dancing, Orchésographie – it is probably as a ‘miniaturist’ that Warlock is best-known today: as a composer of short but exquisite lyrical songs for voice and piano. However, in the liner booklet accompanying Maltworms and Milkmaids, recently released by EM Records, the Vice-Chairman of the Peter Warlock Society, David Lane, explains that ten of Warlock’s songs were – with the permission of his publishers – arranged by various orchestrators, though never printed (some remain lost and others are unattributed). On this disc, the BBC Concert Orchestra and BBC Singers, conducted by David Hill, present those ten orchestrated versions, alongside all of Warlock’s own music for orchestra – seven vocal works and three instrumental pieces – and also two pieces that he originally set for male voices and brass band. Many of the items are world premiere recordings.

Having done a little research into the documentary history of some of these songs and orchestrations, the paper-trail seems quite complex to me! The disc opens with an anonymous orchestration of ‘As Ever I Saw’, for baritone and orchestra. It’s a bright and breezy, tonal and slightly four-square setting of an anonymous sixteenth-century text, but characterfully sung by baritone Ben McAteer whose enunciation is excellent, and which builds to a surprisingly grand conclusion given its brevity. The notes suggest that it was composed in 1918, on a single day when Warlock was living in Ireland.

In a 1963 article I.A. Copley suggests that Warlock himself recomposed ‘As ever I saw’ (or ‘The Fairest May’) for voice and string quartet – a manuscript exists dated 6th November 1930 – though he says that it was sufficiently different to the original song to merit being viewed as a new setting. Copley goes on to suggest that Warlock re-wrote the song when he learned, towards the end of 1930, that the baritone John Goss planned to programme his earlier setting, which the composer now found dissatisfactory, and Goss gave the ‘first performance of the ‘new and improved’ setting on 27 September 1930. And, in fact, Warlock had also set the same text in a song titled ‘My Lady is a pretty one’, for voice and string quartet. The original manuscript of the latter is dated 1919 but the song was not published (in facsimile) until I956.[1] Clearly the textual history and palimpsests of some of these songs make for quite a maze.

But, I digress. ‘Mr Belloc’s Fancy’ (1921/1930 orch. Frederick Rye) and ‘Captain Stratton’s Fancy’ (1921 orch. Peter Hope) are similarly boisterous settings of texts by Sir John Squire and John Masefield, praising beer and rum respectively. McAteer, robust of voice and crisp of diction, enters fully into the spirit, and the orchestral playing is punchy and incisive, though allowing for some tasteful rubatos and subtle changes of mood when the text prompts. ‘Milkmaids’ (1921) is somewhat gentler (and presented here in the string-only orchestration), though no less direct in its celebration of the diverse qualities of milkmaids that might be admired, not least that they “have kisses plenty when Ladyes have but few”. It’s beautifully sung, and McAteer points the text effectively to highlight the girls’ “wanton rowling eye” and “pettycoats of redd”. I did wonder, though, if the baritone is rather too urbane here, the oft-repeated refrain, “Hy tranonny, nonny with hy tranonny no” just a little too RP?

One might be tempted to make the same charge of ‘The Countryman’ (1926) but Gerrard Williams’s light and graceful orchestration with subtle instrumental counterpoints to the vocal line – some super oboe playing here – and the vigour of McAteer’s final invitation (“Then, care away, and wend along with me.”) make the measured approach fitting; and, ‘Yarmouth Fair’ (1924), which was orchestrated by Kenneth Regan for 1200 school-children to perform at the Royal Albert Hall, appropriately balances decorum and swagger. McAteer proves an engaging storyteller.

Similarly, he enters the theatrical spirit of ‘Maltworms’ (1926), which Warlock jointly composed with Ernest Moeran when the two young men were sharing a house in the village of Eynsford in the mid-1920s (and when their rabble-rousing – wine, women and song, pretty much sums it up – became infamous). Composed for a local drama group’s play, Hops, ‘Maltworms’ was originally it was scored for brass band, but Warlock later orchestrated the work. There’s evidence of that brassy panache in the latter arrangement, though, which the BBC Concert Orchestra enjoy, and the strident shrieking of McAteer’s impersonation of the narrator’s inebriated wife, Tib, is complemented by the hearty chorus of the men of the BBC Singers. Meanwhile, the ladies of the BBC Singers trip lightly through the modal melody of in ‘Little Trotty Wagtail’ (1922 orch. David Lang), and there’s some aptly spiky pizzicato playing here; in ‘The Birds’ (1926), a setting of Hilaire Belloc, the female voices bloom tenderly, though I find this song a little on the sentimental side.

‘A Sad Song’ (1926) and ‘Pretty Ring Time’ (1925) are the only two songs which Warlock himself orchestrated. The former, set tenderly for strings and wind quintet, is sung with a lovely radiance by soprano Nadine Benjamin; ‘Pretty Ring Time’ – a setting of ‘It was a lover and his lass’ – employs larger forces, including glockenspiel, drums and celeste, but it remains airy and bright, with light pizzicatos supporting the frolicsome vocal line, and coloristic counterpoint from the woodwind.

We hear the ‘darker’ side of Warlock too. ‘Sorrow’s Lullaby’ (1926-27) sets a poem by Thomas Lovell Beddoes for soprano and baritone soli and string quartet. It’s given here with full string ensemble accompaniment. (Interestingly, the Scottish music critic, scholar and composer Cecil Gray observed, “I am inclined to think that the work could have been more satisfactorily realized by a more extended combination of chamber instruments such as that employed in the ‘Curlew’”.[2]) McAteer and Benjamin negotiate its melodic angularities and chromatic wanderings persuasively, conveying Warlock’s sensitive response to the text. In one stanza which illustrates the thoughtfulness of the text setting, Benjamin wonders “What is that sound, so soft, so clear”, her soprano gentle but glossy; but the following line leaves the poetic image unsupported, vulnerable, “Harmonious as a bubbled tear”, before a well-judged vocal exclamation: “Bursting, we hear?”

The disc includes three instrumental works by Warlock. There’s the Capriol Suite, naturally, but perhaps of more interest is An Old Song (1917-23). Based on a Scottish-folk tune, it reveals its Delian influence in its rich divided strings, expressive woodwind solos, and a bass line in which the pedal notes slide chromatically. It’s given an atmospheric rendition by the BBC Concert Orchestra – Warlock said it was inspired by the Cornish moors – and there are mainly eloquent, yearning woodwind and horn solos. The single-movement Serenade for strings (1921-22) was dedicated to Delius on his sixtieth birthday. The lilting rhythms recall, particularly, On Hearing the First Cuckoo in Spring. And, again, there are luscious string textures against which solo voices stand out lucidly. But, there is some rhythmic vigour and counterpoint too. Hill and the BBC Concert Orchestra string players take their time – their rendition is almost a full minute longer (at almost nine minutes) than the recording by Sir Neville Mariner and The Academy of St Martin in the Fields – and the spaciousness does the Serenade good service.

The aforementioned Gray once described Warlock as ‘the supreme carollist of modern times, possibly the greatest since the anonymous masters of the Middle Ages’. The ladies of the BBC Singers perform Reginald Jacques’s arrangement for strings and baritone of Warlock’s ‘Adam Lay YBounden’ (1923), capturing both the brightness and the warmth of Warlock’s melody and building effectively to the final praise: “Deo gratias!” ‘The First Mercy’ (1927), which sets a poem by Warlock’s close friend Bruce Blunt, is heard in two versions: Raymond Bennett’s version for soprano and small orchestra, and William Davies’s 1967 version, originally for full orchestra but here played by strings alone. In the former, Benjamin infuses the carol text with intensity of feeling while maintaining apt decorum. Davies’s carol has a lovely warmth and lilt.

The disc closes with the Three Carols for Chorus and Orchestra (1923) which were Warlock’s response to a request from Ralph Vaughan Williams for some carols with orchestral accompaniment for a concert with the Bach Choir. ‘Tyrley, Tyrlow’ has tripping lightness, a spirit of good cheer, as well as some asymmetrical rhythmic swerves. It put me in mind of John Rutter – while the vibrant orchestration would be worthy of Leroy Anderson! In contrast, ‘Balulalow’, which sets a sixteenth-century translation of a poem by Martin Luther, is quietly affecting, the chromatic shades in the muted strings and wordless chorus – subtly juxtaposing major and minor tonalities – expressively colouring the modally tinted solo soprano line (Rebecca Lea). ‘As I Sat Under a Sycamore Tree’ provides a rollicking conclusion.

It’s interesting that Copley suggests that Warlock’s piano accompaniments are ‘not especially idiomatic, more contrapuntal than pianistic, often dense with quasi-orchestral textures’ and that ‘they are rarely pianistic in the sense that any conventional nineteenth-century song-writer would have understood the term’. Judging from the recordings here, Copley’s proposal that ‘their contrapuntal texture gives one the impression that they represent simplified piano versions of accompaniments conceived in instrumental terms as chamber music’ may well be justified. And, in this regard, one might hope that EM Records will turn its attention to Warlock’s vocal chamber music at some point in the future – both those works which were originally scored for this medium, including The Curlew, ‘My Lady is a Pretty One’, ‘Sorrow’s Lullaby’, and those voice and piano songs that were subsequently transcribed: ‘My Gostly Fader’, ‘Corpus Christi’, ‘Take, O take’, ‘Mourn no more’, ‘A Sad Song’ and ‘Sleep’, for example.

This disc makes a fine case for Warlock’s musical energy, discipline and imagination. His mentor and friend, Bernard van Dieren, wrote to him, after receiving some early songs in 1919, that ‘reading through them I felt a warm tear somewhere behind my eye running down to my heart. … They are so sweetly sad and so infinitely lovable. … These are those things that come out of one as the precious substances out of the wood ooze out of the wounds made on the tree’s trunk, your melody … “weeps so gaily and smiles so sad”‘.[3] I can’t put it better than that.

Claire Seymour

Peter Warlock: Maltworms and Milkmaids

Nadine Benjamin (soprano), Ben McAteer (baritone), BBC Singers, BBC Concert Orchestra, David Hill (conductor)

EM Records CD080 [73:52]

[1] I.A. Copley (1963) ‘Peter Warlock’s Vocal Chamber Music’, Music & Letters, 44(4), pp. 358–370.

[2] Cecil Gray (1934) Peter Warlock: A Memoir of Philip Heseltine (London: Jonathan Cape): 34.

[3] Letter from Bernard van Dieren to Philip Heseltine, undated, 1919, quoted in Fred Tomlinson (1978), Warlock and van Dieren (London: Thames): 20.