This is the excellent David Alden 2018 production from Covent Garden. Here is how it fared at the War Memorial Opera House.

It fit like a glove due to strong casting, and the rigid musical control of conductor Eun Sun Kim, and the sheer brilliance of the production — its magnificent architecture and the consummate telling of Wagner’s first go at his last opera (Lohengrin is Parsifal’s son).

In the Wagner canon Lohengrin follows Tannhäuser and Der Fliegende Holländer (Rienzi will be admitted in 2026 when Bayreuth, overruling Wagner, stages it). The newly minted “gesamtkunstwerk” Lohengrin composer is in his richer dramatic phase, his stories/poems less philosophically refined, therefore allowing considerable interpretive latitude.

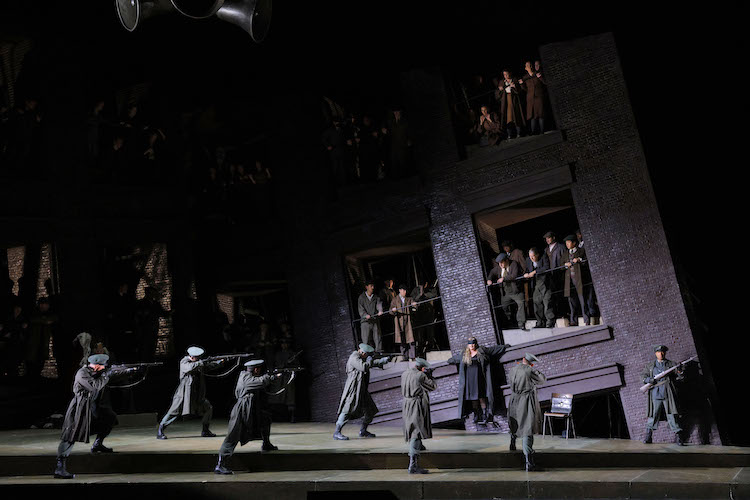

David Alden seizes this weakness to commit Wagner to a supposed divine purpose, one that overrides human desires, demanding their sacrifice, and advocates the use of human might to achieve a perceived higher purpose. The Alden Lohengrin tragedy went far beyond the sacrifice of Lohengrin and Elsa (lead photo), and therefore humanity, to the triumph of might.

Set designer Paul Steinberg effected this suffocating world with massively oversized architectural elements seen from a dizzying perspective, elements that moved to assume evermore overpowering stances. Stage director David Alden effected human desires in the dark, animal like coupling of Telramund and Ortrud in the second act, and the white purity of the unconsummated marriage bed in the third act, both acts manifesting the futility of human feeling.

This Lohengrin ended with the swan child Gottfried raising his sword to the massive sonic strokes of Wagner’s closure. A brutal ending.

Conductor Eun Sun Kim established firm musical control from the first whispered sounds of the prelude. The War Memorial Opera House does not offer the magical acoustic of Bayreuth, thus the musical unfolding of the Wagner poem was procedural, save the magical moments when this conductor unlocked all fetters to the lyricism of Wagner’s poetic development, notably first in Elsa’s dream, then in Ortrud’s diatribes, in Telramund’s sniveling, and finally in Lohengrin’s pompous revelations. As is her wont the maestra made the big moments huge. And hugely satisfying.

Much like the musical telling, the narrative unfolding of this made-over teutonic tale was procedural. Given that the set established a Nazi era, western world, Alden was able to settle into each of the opera’s moments without adding fascistic editorial. Lohengrin and Elsa, Telramund and Ortrud remained human, feeling creatures — if on superhuman scale. Their situations and movements were sometimes worldly, sometimes symbolic, and always painstakingly structured dramatically.

Like the music, the narrative was an agglomeration of carefully formed episodes. Though Lohengrin is of extended length, dramatically unfolding moment by moment by moment, Alden and the maestra maintained a steady, even dramatic tension. We always cared about the purity of love (and its purpose) of Elsa and Lohengrin, and were repulsed by the nefarious intentions of Ortrud and Telramund. It was a world of black and white, both colors of divine motivation, Wagner tells us. In the Alden production it was not for us to judge (and our sympathies did wander from time to time to Ortrud and Telramund), only to recognize that it would be the sword that would prevail.

In a pre-curtain speech San Francisco Opera General Director Matthew Shilvock felt the need to offer comfort for our eventual discomfort with the politics of this Lohengrin. I confess that I soon saw Joe Biden as the ancient King Heinrich and Lohengrin as Donald Trump and Ortrud and Telramund as intruders who slipped through our southern border — hardly the intention of this London based director. Mr. Shilvock, less specifically, invoked Israel and Ukraine. For Wagner, as interpreted by Alden, it was purely philosophic.

It was a cast of like voiced singers — vibrant, young sounding, beautiful voices that gave immediate life, depth and urgency to Wagner’s poem, enhancing David Alden’s disturbing revelations of its inflammable subtexts.

Former Merola participant, tenor Simon O’Neill, now 52 years old, is a Lohengrin of youthful heroic voice (jugendlicherheldentenor), perfectly suited to be the son of Parsifal. His voice exudes the purity, clarity and force needed for a knight imbued with divine purpose. He gracefully overwhelmed Telramund in their first act battle, returned for the magnificent, second act Rossini-like finale, and mesmerized us with his third act confession, laid out in unflagging, huge volume.

Telramund was sung by baritone Brian Mulligan in his role debut. Once San Francisco Opera’s go-to baritone for whatever role you can think of. Mr. Mulligan has found his place as a heroic baritone, hints of which first appeared when he sang the King’s Herald in San Francisco Opera’s 2012 Lohengrin (and as well in the Met’s unfortunate production last year). His golden, bell like tone made his strutting as the first act pretender and his second act manipulation by Ortrud even more pathetic.

The King’s Herald was sung by Thomas Lehman. Fitted with a mechanical prosthetic leg, he brought huge presence to this career building role. Mr. Lehman is of fine, heroic voice, that enabled him to create a personage who accepted force and violence at any cost. King Heinrich was sung by Kristinn Sigmundsson, a role he sang as well in the 2012 production. He projected abject weakness and vulnerability in his ever more declined vocal estate.

Elsa was sung by former San Francisco Opera Adler Julie Adams. Mlle. Adams has all the vocal qualities of a young dramatic soprano, a voice of weight and purity that uniquely qualifies her for the first three Wagner heroines (though she doesn’t list Senta in her repertory). Moreover she is able to physically project the youthful, innocent fortitude of these heroines. Her spectacular delivery of her dream in Act 1 planted her heroic vision in our hearts, only to have her shatter it with the aggressive demands of her marriage bed.

Ortrud was sung by Romanian mezzo soprano Judit Kutasi. Like all Ortruds, everywhere, she got the biggest ovation (all were huge), and that’s because she has the loudest music, and has the most defined and pleasurably complex character. Mme. Kutasi brought gusto and great pride to this Ortrud, in forceful, dark and solid voice. She masterfully manipulated both Elsa and Telramund, satisfying our urges to shatter the fantasies and aspirations of these two victims.

Finally the role of the citizens of Brabant was played by the San Francisco Opera Chorus. It is one of the biggest and most difficult chorus roles in the repertory. Along with the San Francisco Opera’s orchestra, its chorus is world class. The chorus role was executed with absolute precision within complex choreography, in exquisite voice.

It was an evening of high level and important art at San Francisco Opera.

Michael Milenski

War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco. October 18, 2023