Homelands is the title of this programme, curated by pianist and writer Aron Goldin and released by Rubicon last October. However, in the context of creative artists’ representation of ‘home’, one cannot ignore the parallel theme of ‘exile’, and this disc focuses largely on Romantic writers’ and composers’ sensitivity to the themes of exile and alienation. The approaches to these themes as represented in this recital programme are diverse, even disparate, and that is probably appropriate. European Romanticism was at least in part shaped by the consequences of the Napoleonic Wars, what one might term the first modern world war, with displacement becoming an abiding idea. But, equally, such displacement might be conceived in terms of a fragmentation of psychic identity. It is interesting that the OED’s definition of ‘wretch’ includes, ‘One driven out of or away from his native country; a banished person; an exile’.

Among the British poets of the age, Coleridge repeatedly expressed the horror of exile and alienation from home and family, depicting the isolation of the Ancient Mariner, the ‘Wanderings of Cain’ and, in ‘Dejection’, the loud screaming of the “little child” who “Upon a lonesome wild, / Not far from home … hath lost her way: / And now moans low in bitter grief and fear”. In ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, Keats’ image of “faery lands forlorn” draws the speaker back from his visionary journey. But there were also those who saw exile as liberation. Lord Byron, for example, one of the most ‘international’ and cosmopolitan poets of the age, wrote buoyantly of the “Self-exiled Harold” who “wanders forth again”. Yet, even Byron – who experienced exile from Scotland to England at the age of ten, upon the death of a parent and the inheritance of his title – expresses in his early poems sorrow at having to leave his ancestral lands and hopes eventually to “mingle his dust” with his forebears.

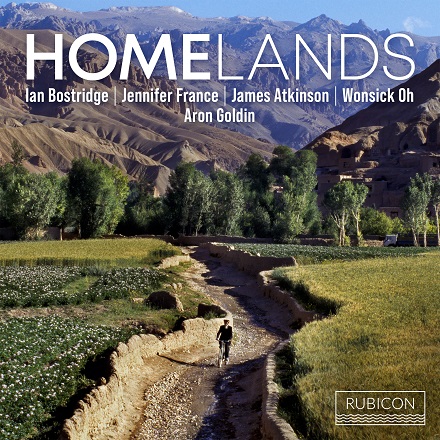

Aron Goldin’s project began life as the programme for the final recital of his Advanced Diploma in Piano Accompaniment at the Royal Academy of Music. A charity concert followed, on World Refugee Day in June 2022, with Olivier Award, Bafta and Tony Award winning actor Sir Simon Russell Beale reading poems by Auden, Brecht and Carol Ann Duffy alongside ancient Hebrew and Chinese poetry. The performance raised over £200,000 for the 30 Birds Foundation, a charity that enabled 450 Afghan school girls to escape Afghanistan and fly from Kabul to Canada. The ensuing album, which features performances by tenor Ian Bostridge, baritone James Atkinson, soprano Jennifer France and bass Wonsick Oh, entered the Classical Music Charts at number 10 in October last year. It includes both familiar musical variants on the theme by Schubert, Schumann, Mahler and Tchaikovsky, as well as repertoire by Duparc, Wolf and Fauré and a song by the Korean composer Dong-Su Shin.

Ian Bostridge gets the recital underway with Mahler’s ‘Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen’ (I’ve become lost to the world) from the Fünf Lieder nach Rückert (1901), in which exile is presented as a welcome retreat into the artist’s ‘self’, a place of stillness dedicated to art and the representation of love. It’s perhaps significant that on the sole occasion that Mahler performed these songs as an accompanist, with the Dutch baritone Johannes Messchaer, he placed ‘Ich Bin der Welt Ahhanden Gekommen’ last in the sequence. Bostridge has full control of the long lyrical lines, creating a wonderful sense of tranquillity which complements Goldin’s sombre but not characterless introductions and interweavings, in which subtle rubatos and delays evoke deep sentiments. The vocal rise, “Sie mag wohl glauben, ich sei gestorben!” (They may well believe, I have perished), brings intensity, and Bostridge exploits the harmonic roving in the subsequent reflections, “Ob sie mich für gestorben hält” (The world may think I am dead). The final utterance, “In meinem Lieben, in meinem Lied! (I live for love’s sake, for song) is a wonderful fusion of rapture and stillness.

Bostridge also sings three songs from Schumann’s Liederalbum für die Jugend Op.79 (1848), which was written in part as a birthday gift for the composer’s daughter. Marie. ‘Im Zigeunerliedchen I and II’ belong to each other as a vivid pair. In the first, a gypsy lad’s plight is made direct and immediate by the sharply lit vocal and pianistic characterisation, Bostridge brightening and hardening his tenor to embody the boldness of the lad who steals money from soldiers but manages to evade his tragic fate. The performers capture the lad’s confidence in this short, witty vignette. The yearning minor 6th at the start of ‘Zigeunerliedchen II’ conveys every ounce of pain that seeps through the tears of a young gypsy girl who is stolen from her homeland; the triplet figures pulse forwards, evoking anguish, then voice and piano coalesce in hushed unisons. The effect is magical, brevity no bar to poignancy and Bostridge’s control of the rolling phrases consummate. Schumann turned to Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell in ‘Des Sennen Abschied’. Here, the contrast between the piano’s left-hand drone and the brilliance of the right-hand’s melodic clarity creates a forthright ambience against which Bostridge projects the Tyrolean Volkslied with tenderness injected with moments of vigour and passion.

The three songs of Schubert’s Gesänge des Harfners form Bostridge’s final contribution to the disc. Goethe’s tale of Augustin the Harper, in Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre, is certainly the stuff of German Romantic suffering, telling as it does of an Italian nobleman who fathers a child after an incestuous relationship with his sister, Sperata, and retreats, his soul in agony, to a monastery where he seeks solace in music. Bostridge’s tenor has darkened over the years and he has the vocal weight, alongside his customary expressive insight, to pack an emotional punch in these bleak songs of remorse and despair. In the first song, ‘Wer sich der Einsamkeit ergibt’ (He who surrenders to loneliness), there’s a telling sense of forward movement with the harper’s cry, “Ja! laßt mich meiner Qual!” (Yes! Just leave me to my torment!), the piano triplets light and tripping – for his torment visits him, as a lover visits a secret mistress, and he cannot find true solitude. Subsequently, Bostridge’s subdued delivery, lifted at times by injections of colour and beautifully shaped melodic ornamentation, conveys the protagonist’s longing for the ultimate aloneness of the grave.

The varied repetitions of the long phrases of ‘Wer nie sein Brot mit Tränen ass’ communicate an underlying bitterness which swells then suddenly retreats, repressed but not quelled – as Goldin’s final, stabbing dissonant outburst confirms – as the harper accuses the gods of injustice to humanity. A sort of steadiness and detachment comes in the simple, strophic ‘An die Türen will ich schleichen’ (I’ll steal from door to door) in which the harper seeks dignity through the role of the Romantic wanderer.

There’s more Schubert from Wonsick Oh whom I first heard perform, with Goldin, at the Oxford Lieder Festival (then so-named) in October 2022. The lovely grain in his rich bass voice is exploited expressively in ‘Wanderers Nachtlied’ (D768), though I find the tempo rather too slow, and Wonsick’s German doesn’t always convince. I’d like a bit less vibrato, too, and there’s sometimes a slight sense of fragility when the voice climbs higher. The bass’s other contributions were all performed during the aforementioned emerging artists platform in Oxford, and they find the singer on more comfortable territory. The yearning melody of Rachmaninov’s ‘Do not sing to me, my beauty’ (from 6 Romances Op.4) is beautifully introduced by Goldin, and Wonsick balances a dreamy wistfulness with focused rhetoric – building to an operatic climax, then receding into poetic privacy – the piano’s elaborations and exhortations ever eloquent and deeply engaging, none more so than the major-minor fluctuations of the close.

Both performers create a wonderfully cushioned sound-world in Tchaikovsky’s ‘Nyet tolko tot kto znal’ (Only those who know longing, from 6 Romances Op.6), the climax brief but effusive and emotively impactful. And, there’s a welcome opportunity to hear again ‘Oh Mountain’ by the Korean composer, Dong-Su Shin, which was composed in the aftermath of the Korean War, and which evidently means a great deal to Wonsick, whose performance is commanding.

Henri Duparc composed only seventeen songs for solo voice, and Jennifer France sings three of them here – coincidentally the same three that Mary Bevan chose for her disc, Voyages,with Joseph Middleton – starting with the well-known Baudelaire setting, ‘L’invitation au voyage’. The tempo is well-judged, creating a sustained flow, while Goldin’s rippling sextuplets are fluid and nuanced, creating a dreamy otherworld. France captures the dramatic, even ‘operatic’ quality, of the song, allowing the passionate impulses of the language to swell richly and lyrically, always attentive to the text, then sinking into a softness suffused with sensuous sweetness.

Composed when he was just 37 years old, Duparc’s last song, ‘La vie antérieure’ (A previous life), begins in more pensive fashion, and if the imagery of sensuous repose (“les voluptés calmes) inspires lush vocal ardour, then there is an underlying sadness which France and Goldin undoubtedly convey. The text may speak of blue skies, waves and naked slaves drenched in perfume – “Au milieu de l’azur, des vagues, des splendeurs/ Et des esclaves nus, tout imprégnés d’odeurs” – but France’s vocal line is hushed and pure, retreating into a secret grief (“Le secret douloureux qui me faisait languir”). The chromatic slippages of Goldin’s heady postlude wonderfully embody the spirit of sensual pining. ‘Romance de Mignon’ is a free translation by Victor Wilder of Goethe’s ‘Kennst du das Land’, is less frequently heard. France makes the simple vocal line shine and glisten, and exhibits superb control in her deployment of contrasting dynamics and colours. It’s hard to imagine a lover resisting the implorations of the passionate refrain: “Le connais-tu, le connais-tu? Là-bas,/ Mon bien-aimé, courons porter nos pas …” (Do you know it? Do you know it? There, My beloved, let us make our way …)

Baritone James Atkinson sings a selection of songs from Schumann’s Liederkreis Op.39. They are all tastefully performed, technically assured and pleasing on the ear, but perhaps too much so – there’s little of Eichendorff’s Romantic anguish and phantasmagoria here. In ‘Der Fremde’, the protagonist finds himself in a foreign land, “beyond the red lightning”, alienated from his homeland and longing for that quiet time, “When I too shall rest Beneath the sweet murmur of lonely woods, Forgotten here as well” (“Rauscht die schöne Waldeinsamkeit,/ Und keiner kennt mich mehr hier?”), but Atkinson doesn’t really make one feel the enveloping darkness, literal or figurative. Similarly, the rapture experienced by the poet-speaker at the close of ‘Schöne Fremde’ (Beautiful foreign land) is somewhat muted. ‘Wehmut’ (Sadness) feels a bit four-square.

However, there is some fine singing. ‘Intermezzo’ pulses with longing (Goldin’s syncopations do strong expressive work here), and Atkinson varies and colour to create immediacy in the dialogue of ‘Waldesgespräch’. He grasps the dramatic mettle of the latter, while Goldin skilfully makes the discursive structure cohere. ‘Mondnacht’ is delicate and tender, if a bit on the slow side; Goldin’s gentle repeating semiquavers quiver with a lovely combination of hesitancy and grace. There is passion and joy in the cycle’s concluding song, ‘Frühlingsnacht’.

Goldin may be a relative newcomer, but this is an impressive project which demonstrates an acute musical, professional and cultural focus. His range is impressive: his debut novel will be published by Pushkin Press in autumn 2024, as part of a two-book deal. In spring 2024, he will record his second album with South African soprano Masabane Cecilia Rangwanasha. We’re certainly going to be hearing a lot more from Goldin, in one form or another.

Claire Seymour

Homelands: Ian Bostridge (tenor), Jennifer France (soprano), James Atkinson (baritone), Wonsick Oh (bass), Aron Goldin (piano)

Rubicon RCD 1117 [72:00]