Bellini’s second to last opera, Beatrice di Tenda, was not a success at its 1833 Venice premiere, though subsequent performances are said to have overcome the opera’s macabre horrors through the brilliant performances of Giuditta Pasta, the bel canto diva-of-the-day, as Beatrice.

Much the same can be said of the Peter Sellars / George Tsypin production of Beatrice di Tenda that opened last night at the Opéra Bastille. The horrors of the opera were made very present — the villain was truly vile, the love intrigue was equally vile. The production’s redemption was the performance of the American diva Tamara Wilson as Beatrice. (see lead photo)

As the voice of Giuditta Pasta was described by famed early nineteenth century opera aficionado novelist Stendhal, la Wilson too is a perfect soprano sfogato (aka soprano assoluto), in other words a heroic soprano with extended upper and lower ranges, able to negotiate complex fioratura with grace and ease. Mme. Wilson sings both Turandot and Isolde, and now Beatrice. Unlike la Pasta, la Wilson does not strain to nail and extend a high D, nor does her voice assume different timbres in different ranges. It remains full and warm throughout, with a plenitude of colors, and an unerring sense of pitch in the dramatic leaps Beatrice executes in her most extreme moments. In equally intense, reflective moments she smoothly negotiates Bellini’s soaring lines, embellished with clearly executed, perfect trills. Bel canto indeed.

Beatrice, just now in director Sellars’ Paris, unfortunately champions progressive political causes. It worked out well with her first husband, but he died young. She had the power to elevate a rising young politician to a position of great power, and he became her husband, later becoming corrupt. She then championed a young, progressive reformer who unfortunately fell in love with her. Unfortunately Agnese, a beautiful young woman, is in love with Orombello, the progressive reformer, though Filippo, Beatrice’s corrupt husband is madly in love with Agnese. German mezzo-soprano Theresa Kronthaler sang the role. She too qualifies as a soprano sfogato, plus she boasts a voice of truly magical beauty, well able to bewitch Filippo, if not Oronbello. Mlle. Kronthaler’s roles include Sieglinde.

San Francisco finished, New Zealand Māori tenor Pene Pati sang Orombello. Mr. Pati excels brilliantly in the bel canto repertory, though he sings the Duke of Mantua and Rodolfo as well. His bows are indeed florid. Famed American baritone Quinn Kelsey sang the villain Filippo with much the same élan that he brings to his signature role, Rigoletto.

Peter Sellars’ production politicizes Bellini’s setting of a moment of early fifteenth century history (history according to opera — not exactly fact), bringing it into our contemporary experience. Sellars emphasized the brutality of Filippo, his corrupt nature and the self indulgences of a dictator encouraged by his attendant sycophants (the 40 or so male voices of the chorus). At other times these male chorus voices are joined by the 45 or so female voices to become the populous abused by Filippo, the corrupt dictator. The populace makes a mighty noise, a real threat to the dictator’s power. The finale choruses are sung from the theater’s upper reaches, thereby including us seated in the theater among their commenting force.

Mr. Sellars adds yet more from his arsenal of theatrical devices. Filippo has a few henchmen armed with Uzi guns or maybe ak47’s, a universal symbol of the brutality of the state. There are two performers of exotic provenance (diversity) — Mäori tenor Pene Pati is joined by his brother, San Francisco finished tenor Amitai Pati as Anichino, here rendered as a brother (not the Bellini friend) to Pene Pati’s Orombello. Amitai Pati is a fine tenor — Toulouse’s Alfredo, ENO’s Ferrando. Certainly the outsized chorus was complimentary to Mr. Sellars concept as well.

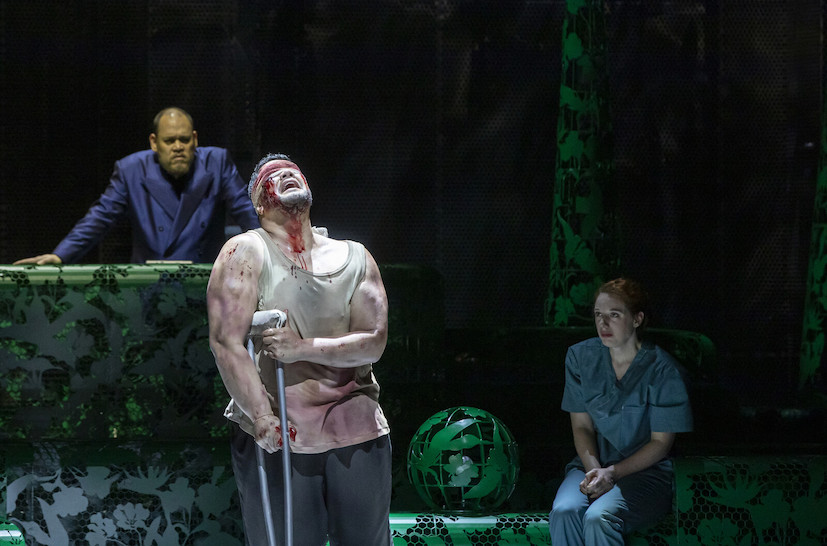

In the end Sellars displayed Beatrice and Orombello’s dying prayers with blood and guts spilled on the stage, Orombello and Beatrice in hideous, physical states, bel canto be damned. Filippo effected his revenge, Mr. Kelsey oscillating between remorse and ferocity, breaking free of the beauty of bel canto to crush those who challenged and betrayed him. The execution by six Uzi bearing thugs was aimed directly at the audience, Beatrice, having forgiven Agnese, begs us not to pray for her, Beatrice, but to pray for Filippo. We, mankind, felt redeemed. All of us.

Peter Sellars again evidenced himself as a potent theatrical mind.

All this bloodshed took place within a huge, complex piece of sculpture that transformed from transparent bright green to transparent bright red, fading to a gray. The huge structure was a mesh back wall with evolving textures. Side walls were reflective to destroy all boundaries. The floor was a manicured French topiary garden, a maze that told us we were in a highly regulated if arcanely governed world. Gardeners toiled to keep it so, and then these gardeners polished the reflective walls as Filippo briefly thought he might have a bit of compassion. Kazakhstan born, American finished designer George Tsypin created this massive piece of art that did not overwhelm Bellini’s small scale opera, though its sickly, luminous, quite important world was well beyond this incidental moment of opera history.

The pit of the Opéra Bastille is a lively place, Bellini’s orchestral sounds pealing forth in political exuberance. British conductor Mark Wigglesworth participated whole heartedly in the Sellars concept. Much of the evening was not devoted to Bellini’s bel canto as much as it was devoted to a rhetorical delivery of text. The recitative moments were deliberately paced, indeed becoming oppressive as the evening progressed — we were being told and told some more. Much use was made of silences to emphasize the political points director Sellars wished to make, interrupting the inbred flow that is the glory of bel canto. Mr. Wigglesworth did provide very effective, informed musical support for the arias, and certainly for the massive choruses, and especially for the final prayers.

It was, of course, a splendid evening, albeit trivial in effect, if not for the spectacular singing of la Wilson.

The costumes were designed by Camille Assad, lighting design was by James F Ingalls, both longtime collaborators of Mr. Sellars. Rizzardo del Maino (Filippo’s confidant) was sung by Taesung Lee.

Michael Milenski

Opéra Bastille, Paris, France. February 9, 2024. All photos copyright Franck Ferville_OnP, courtesy of the Opéra national de Paris