Both operas staged by famed (for many) or infamous (for others) Spanish stage director Calixto Bieito.

Both Parisian Bieito productions bore this stage director’s signature touches — a complex, abstract design metaphor to anchor the action, and lavish use of scatalogical and other visceral imagery that shocks your mind and offends your sensibilities. Actors are placed in high relief, with the daunting challenge of creating this stage director’s vibrant characters.

Great theater and pointed, powerful opera result.

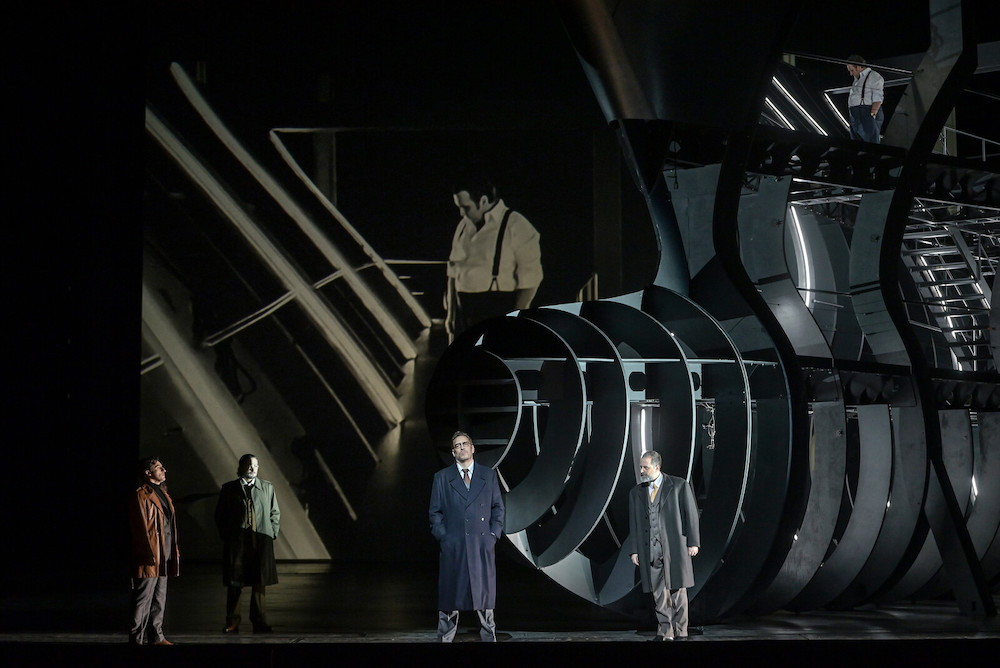

The design metaphor for Verdi’s Simon Boccanegra was a ship, one that had the exposed wooden ribs of old ships as well as elements of an ugly, modern aquatic war machine. As the story unfolded these armored plates were stripped away to create the skeleton of a huge fish-like structure. It was placed off-center on a constantly revolving stage, revealing ever new, surprising perspectives through the use of video. (Lead photo is Nicole Car as Amelia and Lodovic Tézier as Boccanegra in video image. All Simon Boccanegra photos copyright Vincent Pontet / OnP, courtesy of the Opéra national de Paris).

The structure was huge, built so that as it turned an armored tower penetrated the massive. proscenium opening of the Opéra Bastille, swinging out over the pit, aggressively entering our space — 14th century Genoa was at constant war with Venice for the domination of Mediterranean trade routes.

For Simon Boccanegra Bieito obsessed on the Genoese corsair’s seduction of the Genoese patrician Jacopo Fiesco’s daughter Maria. Maria, then sequestered by her father within his palace, died of grief. A child had resulted from the liaison, though the child had been kidnapped. Fiesco, sung by fine Finnish bass Mika Karas, dragged his supplicating — though dead — daughter onto the stage where she remained, in ghostly, mute, guises though the action of the opera, though it was now 25 years later.

At the moment of his death, Boccanegra — sung by French Verdi baritone Ludovic Tézier in a consummate performance — heart wrenchingly reached out to Maria. Though now, at his end, she was no longer there.

To regain/restore his daughter Maria, Fiesco sought his daughter’s lost daughter — sung by Australian Mozartian soprano Nicole Car in newly found Verdian tones — now known by her adoptive name Amelia Grimaldi. In the end the two fathers, Fiesco and Boccanegra, reconcile, a deeply touching scene as rendered by Bieito, Fiesco embracing the dying Boccanegra, holding him upright.

The dramatic center of Bieito’s production was his imposition of a rape of Amelia by Boccanegra’s enemies. Now came classic Bieito images — blood running down Ameiia’s leg as she emerged from a vagina image within the ship’s guts. As well Amelia’s mother Maria appeared, battered and torn, bloody and ravaged. We then understood, and felt, Fiesco’s need for revenge.

Bieito established the sexual tensions he invented for Verdi’s opera as his central focus, not the political resolutions.

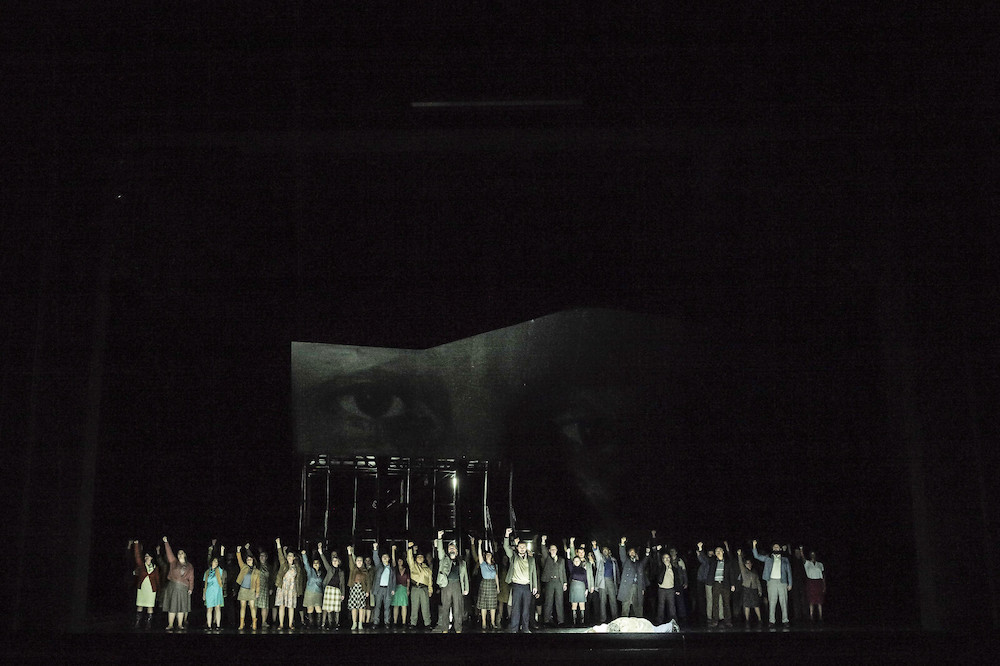

Adorno, Amelia’s intended, sung by American tenor Charles Castronovo and the spurned Paolo, sung by French baritone Étienne Dupuis, were very much on Bieito’s secondary plain, as were the revolutionary Genovese forces sung by the magnificent multitudes of the Opéra national de Paris chorus backing up Boccanegra’s (Tézier’s) truly magnificent cries for peace between Genoa and Venice.

Of great interest was the musical realization of the Verdi score by German early music conductor Thomas Hengelbrock. Mo. Hengelbrock is a famed researcher of historical performance practice, thus we may assume that his slower and more relaxed tempos led to a heightened sense of lyricism — specifically with regard to the Mozartian voice of Mlle. Car. Mo. Hengelbrock did not pursue dramatic punctuation, allowing dramatic effect to slowly grow through crescendo reaching shattering volume — this specifically noted in the monumental finale that concludes Act II.

The Exterminating Angel

Thomas Adès’ 2016 opera The Exterminating Angel is based on the 1962 film of the same name by famed filmmaker Luis Buñuel. The opera was commissioned by the Salzburg Festival, thus the film’s absurdist parody of the haute bourgeoisie attending a dinner after an opera took on even greater absurdity, given the haute bourgeoisie status of the Salzburg Festival.

Just now, a few years later, the opera finds itself in Paris — the city of existentialist Jean Paul Sartre. It is a new production by one of the world’s edgiest stage directors. Though composer Adès conducted the first few performances, the performance I attended was subject to the high strung temperament of English/Danish conductor Robert Houssart. It was electric indeed.

The design metaphor for The Exterminating Angel was a huge, empty, white, round room of solid walls, no windows. There was a huge double door at the rear that never opened. Within the room there were a few chairs, a table, and a black grand piano. The room was soon peopled by 14 well-dressed people coming from an opera performance. Only at the very end of the opera did we learn that this interior room revolved, we saw its finished exterior walls sweep past us to reveal finally the huge double doors from the outside. They opened.

Holding firm to the existential tenet that existence is not essence (i.e. being) the twelve guests of the dinner’s hosts, Lucia and Edmundo de Nobile, discover that there is nowhere to hang their coats, that the maid, before fleeing, has dumped the dinner on the floor. Taking matters into their own hands they create a world, their world, which becomes, little by little, increasingly, bizarrely, destructively absurd.

Thus the guests find themselves unable to leave the de Nobile residence.

Unique to Bieito’s Paris production was a sense of the sharpness of intelligence of the cast, the sharpness and focus of the voices, and the confidence and quite abstract purposes of their movement. There was absolutely no doubt as to the urgent need of these brilliant singers to create a vibrant artistic existence.

There was the overwhelming sense of virtuosity of the composer, demanding the extraordinary virtuosity and musicianship of the singers, plus an immense directorial intelligence behind these two packed hours of this existential discovery.

Bieito signed the production with at least two proudly visceral moments. The first: the guest named Silvia wiped the sh*t off the exposed butt of her brother Francesco. The second, grandly grotesque (though undoubtedly there were more that I missed), was the slaughtering of a sheep to provide food for the self-imprisoned guests — conveniently the two affianced lovers, Beatrix and Eduardo had achieved a love-death, thus they became the meat of the feast.

Bieito encapsulated his telling of the Adès setting of Buñuel’s tale with a child holding a bouquet of sheep shaped balloons, the child bleating, upon occasion, the futility of mere existence.

Edmundo Nobile was sung by Scottish tenor, Nicky Spence, Lucia de Nobile was sung by American soprano Jacquelyn Stucker. The opera diva Leticia Mayer was sung by French/Romanian soprano Gloria Trowel, the conductor Alberto Roc was sung by French bass baritone Paul Gay, his pianist wife Blanca Delgado was sung by British mezzo soprano Christina Rice, the young lovers Beatrix and Eduardo were sung by Egyptian soprano Amina Edris and New Zealand tenor Filipe Manu. Francisco de Avila was sung by American counter-tenor Anthony Roth Costanzo, his sister Silvia de Avila was sung by Irish soprano Claudia Boyle. The Comte Raul Yemenis, an explorer was sung by Canadian tenor Frédéric Antoun, Colonel Alvaro Gomez was sung by American baritone Jarrett Ott, Señor Russel was sung by Canadian bass baritone Philippe Sly, Dr. Carlos Conde was sung by British bass Clive Bayley. The de Nobile butler Julio was sung by British bass Thomas Faulkner.

The costume designer for both Simon Boccanegra and The Exterminating Angel was frequent Bieito collaborator Ingo Krügler. Set design for The Exterminating Angel was by Anna-Sofia Kirsch, set design for Simon Boccanegra was by Susanne Gschwender. Also among the Bieito’s German collaborators were lighting designer Michael Bauer for Simon Boccanegra and Reinhard Traub for The Exterminating Angel. Swiss videographer Sarah Derendinger created the extensive Boccanegra videos.

Michael Milenski

Opéra Bastille, Paris, France. March 17 and 19, 2024