Both of them — her death in Aulide and her resurrection in Tauride, back to back, in a surreal world created by Russian stage director Dimitri Tcherniakov, rendered in overdrive within Gluck’s reformed operatic world by conductor Emanuelle Hahn and Le Concert d’Astrée.

In Aix just now the diptych was twice as long but no less shattering than the Richard Strauss Elektra — though Gluck’s voiceless Elektra had been abandoned back in Aulide.

In Tcherniakov’s Tauride a brutal Oreste, haunted by having killed his mother, was given ample rein to re-enact, repeatedly, the murder of Clytemnestra in a grandiose scene — in Tcherniakov’s surreal dream world the unities of Aristotelian tragedies do not apply. Oreste was sung by famed French Figaro, Florian Sempey, here tensely wound and in sharp voice, exploding brutally to the affections of his friend Pylade, sung with great strength and masculine warmth by French tenor Stanislaw de Barbeyrac, reacting to Oreste’s unleashed fury with equal, brutal blows.

It was very much a Straussian world. We sat at the edge of impending doom for the duration of both Iphigénies, these mythical voices crying out their torments, conductor Hahn extravagantly pulling every possible motif from the Gluck scores, the double winds and brass finding myriad colors and affections amidst the powerful swell of strings. The storm that begins Tauride was sonically absolutely terrifying, echoing to the rafters of Aix’s Grand Théâtre de Provence, the goose stepping march of the Greeks at the end of Aulide was a celebratory, musical apotheosis of war.

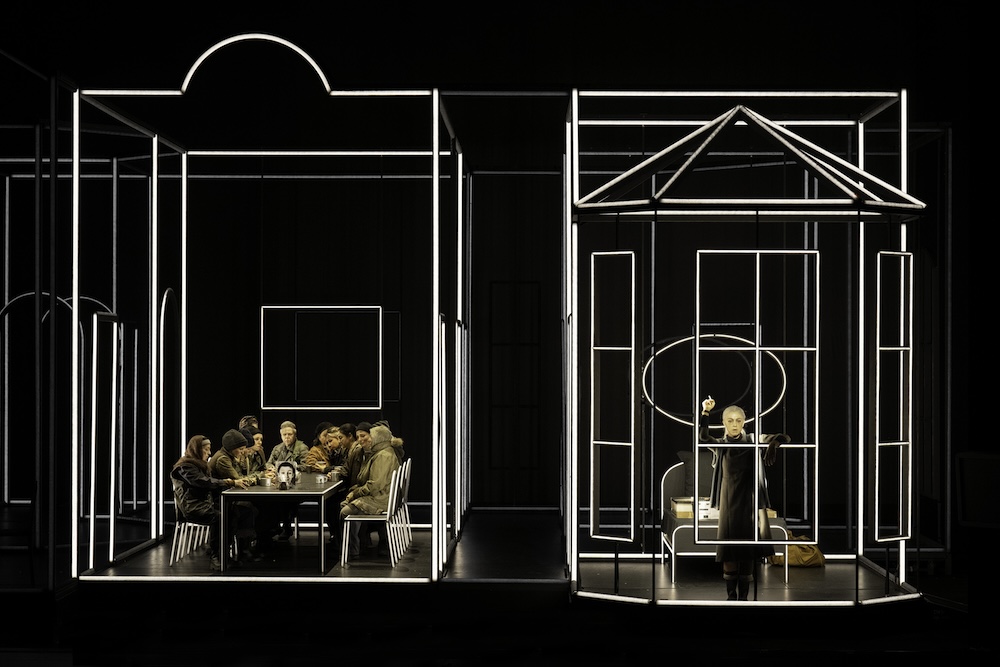

Stage director Tcherniakov began his tale of the two Iphigénies by staging Aulide’s famed overture. Agamemnon was in a dream in which he witnessed the sacrifice of his daughter Iphigénie to the goddess Diane (to secure the goddess’ support of the his war with Troy). The set, like in a dream, was not real or solid, rather there was only a linear structure outlining rooms that became different spaces depending on who was in them, and why. It was a brilliant, surreal space envisioned and realized by Mr. Tcherniakov himself, lighted with astonishing virtuosity by Gleb Filshtinsky, Tcherniakov’s long time collaborator.

As in the Strauss Elektra, and in these Gluck tragedies as told by Tcherniakov, Clytemnestra became the most terrifying of all the characters, because she is the most complex, made so by her vanities mixed with her contorted maternal instincts. A voiced participant in the action of Aulide she became Oreste’s voiceless nightmare in Tauride, towering over everyone in her magnificent coiffure and flowing green gown. Portrayed in Aix by esteemed French mezzo soprano Véronique Gens, Clytemnestra cut a magnificent figure in a voice well known on the world’s major stages.

Iphigénie was sung by American soprano Corinne Winters (lead photo) in a tour de force performance. In Aix, Aulide and Tauride were the continuous tale of one life in two terrifying moments. As Iphigénie is about to be married to the hero Achilles, she must, and willingly does reconcile herself to the sacrifice she must make for the greater good (winning the war with Troy), bowing to the will of her father. Unlike Gluck’s happy ending, in Aix she was not rescued by a deus ex macchina. Instead she was indeed sacrificed, and by the hand of her father — an electrifying moment.

Tcherniakov’s first (of many) coup de théâtre was that the goddess Diane herself did appear at that very moment, lost on the forestage as a bedraggled Iphigénie, Iphigénie herself lying dead on a sleek metal table that served as an altar. The goddess in fact sings Iphigénie’s celebratory words at her salvation, only to find herself, Diane, becoming the Iphigénie of Tauride — an hour and a half intermission occurred between the two operas.

Both Iphigénie en Aulide (1774) and Iphigénie en Tauride (1779) are huge tragedies rendered by Gluck in his reformed opera serial style. This style emulates much of pre-revolutionary French opera — greater use of orchestral colors, orchestrated recitatives, important choruses, and dance integrated into the action. Neither Iphigénies are simple or charming, as is his first reformed opera, the pastoral Orphée et Eurydice (1774 in Paris, though 1762 in Vienna [in Italian]). Both tragedies are of great dramaturgical challenge, made far greater by combining the two into one statement.

In Aix Emmanuelle Hahn took Gluck’s orchestra to and surely beyond its expressive extremes, the orchestral players of Il Concert d’Astrée played with enthused virtuosity, particularly noteworthy was the truly extravagant percussion. The 29 member chorus (including six haute-contras) of Il Concert d’Astrée was magnificent indeed. The chorus had massive responsibilities, from being the Greek people to becoming soldiers, priestesses, etc, moving from costumed participants on stage to black clad choral accompaniments into the pit. Lille’s Il Concert d’Astrée is one of France’s great treasures.

There was however no ballet. The intended music for dance was filled with stage movement by the chorus and the principals — usually some impressively choreographed fighting in addition to considerable goose stepping, not to mention the uncontrollable PTSD seizures (the Greek war with Troy, begun in Aulide, had been going on for 20 years when Tauride began), Plus, and particularly, the hyper realistic staging of the lethal fights between Oreste and Pylade. No choreographer or fight director is credited in the program, though the Tcherniakov production was but the history of a war, the terrifying family calamities only incidental to the war.

As is usual at the Aix Festival, the casting was of superb singing actors. Of great effect was American formed Australian tenor Alasdair Kent as Achilles in Aulide. He found impressive high D’s of a French haute contre as well as finding a braggartly swagger for Tcherniakov’s comic take on this character. No less impressive was the Aulide Agamemnon of Canadian bass Russel Braun who, in his purple suit, found both the vocal warmth of a father and the terrifying responsibility of a sovereign.

Of great effect as well were the high priests (here soldiers), French bass Nicolas Cavallier as Calchas in Aulide, and French baritone Alexandre Duhamel as Thoas in Tauride, both men finding the rough voices and the physical brutality of hardened warriors. The calming voice of Arcas in Aulide was beautifully sung by Polish baritone Tomas Kumięga. Greek-Canadian soprano Soula Parassidis sang the goddess Diane.

The sweep of Tcherniakov’s war, his exaggerated familial tensions together with the Straussification of the Gluck score created an unrelenting, intense continuity that precluded parsing the two operas into their myriad parts — no arias were applauded. It can be noted that the indefatigable Iphigénie, Corinne Winters, did show some fatigue towards the end of Tauride, flatting a couple of notes in her “Je t’implore et je tremble, ô Déesse.”

Michael Milenski

Grand Théâtre de Provence, Aix-en-Provence, July 8, 2024. All photos copyright Monika Rittershaus, courtesy of the Aix Festival.