The Salzburg Festival’s Felsenreitschule is home to most of its productions of twentieth century opera, just now two Russian operas based on novels by Fyodor Dostoevsky — Mieczyslaw Weinberg’s The Idiot (1987, though premiered in Mannheim in 2013), and Sergei Prokofiev’s The Gambler (1917, though revised for its 1929 premiere at Brussel’s Monnaie).

Both Dostoevsky novels, The Gambler (1866) and The Idiot (1868/69), are at least somewhat autobiographical, the events and personages of his life are amplified in the urgencies developed in both novels. Dostoevsky had indeed lived for a time in Switzerland, he suffered from epilepsy, had a gambling addiction, begged money from his family, fell in love with a woman named Polina, etc.

Given operatic advance planning it is likely that this 2024 double Rock Riding School programing was conceived before Russia’s February 24, 2022 bet that it could take Ukraine in a day or so. That bet lost, things Russian have lost their luster for westerners, Dostoevsky’s exposition of the Russian psyche adding no polish whatsoever to the tarnished Russian image.

When becoming operas both The Idiot and The Gambler lose much of their nineteenth century ambience, the reduced plots and personages sacrifice much Dostoevsky tonality. Both operas are more like short stories than they are like novels, short stories thrusting a formed character into a situation then finding a resolution. Both Prokofiev and Weinberg then color their stories with the modernist compositional tendencies of their time — think Igor Stravinsky and Dmitri Shostakovich.

As do directors when they stage their operas.

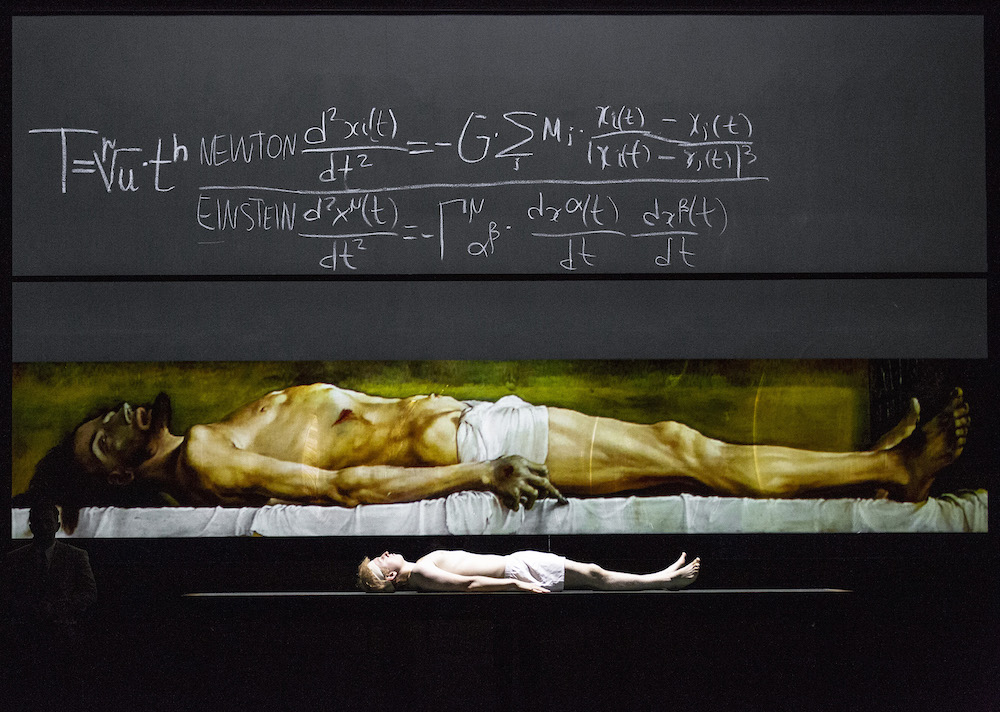

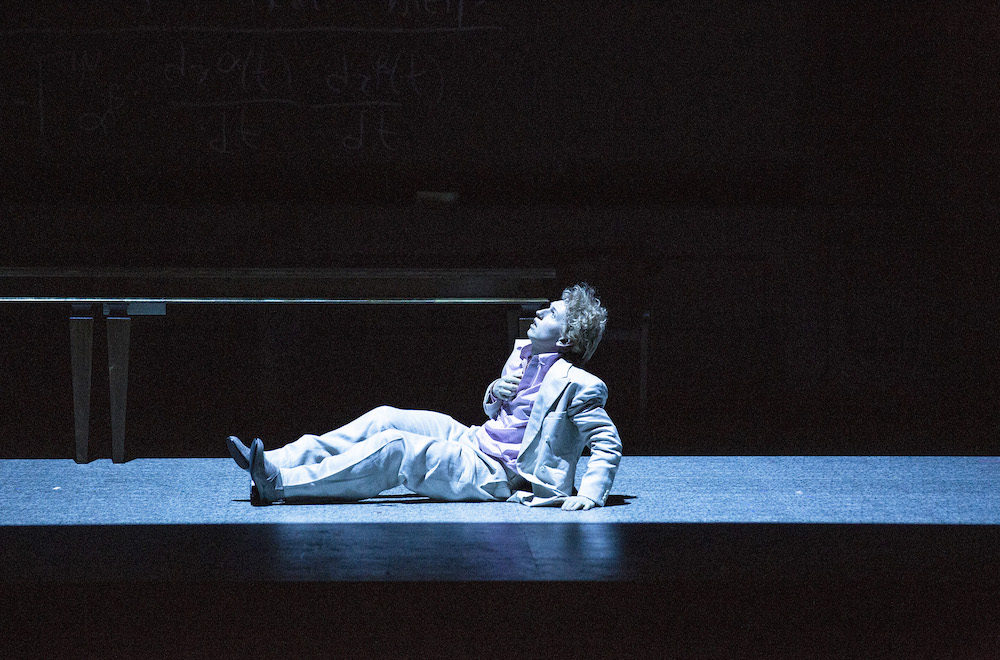

The Salzburg Festival entrusted the staging of The Idiot to Polish director Krzysztof Warlikowski, his designer wife Maľgorzata Szczęśniak and their team, video designer Kamil Polak and lighting designer Felice Ross. The Rock Riding School is a vast expanse of stage in front of a cliff. Ignoring the cliff Warlikowski erected a long (very long), low, polished wood cross-stage wall, embedded within it was a large screen for projections, plus there was the usual Warlikowski box that rolled out for intimate, domestic scenes — the murder of Natascha as example.

The libretto, construed by the composer, closely follows the novel, losing only a few extraneous characters. The idiot, a prince who is a perfect Christian, meets a man of affairs on a train who is smitten by a femme fatale. Their lives become entwined as they both follow Natascha (the femme fatale) through her brief, twisted life and inevitable death.

Composer Weinberg escaped Poland during the WWII German invasion, fleeing to Russia where he lived a rich, musical life as a Soviet composer. Of his seven operas he considered The Passenger (1968) to be his best, in fact to be the most important of all his works, though the opera had its premiere finally in Germany in 2006. Weinberg’s works have been rediscovered only in recent years,

Stylistically Weinberg is similar to Shostakovich, though without the sarcasm. More sumptuous than Shostakovich he mixes free tonalities, atonalities and polytonalities in often hugely complex rhythms. His vocal lines are melodic, if not flowing, requiring singers of considerable technique with precise ears. Weinberg’s orchestra for The Idiot was huge, unleashed under tight control by Lithuanian wunderkind conductor Mirga Graźinytè-Tyla — she is the current music director of the Birmingham Symphony Orchestra.

Composer Weinberg takes nearly four hours to tell his tale. Of great orchestral moment was the Idiot’s epileptic seizure, requiring all possible virtuosity from the Vienna Philharmonic to support the massive seizure grandly, indeed grotesquely enacted by Ukrainian lyric tenor Bogdan Volkov, a singer of beautiful voice, great presence and phenomenal stamina. Mr. Bogdan’s subtle acting skills were well matched by Lithuanian soprano Austrine Stundyte (Warlikowski’s 2023 Salzburg Elektra) as Natascha, who, staring directly into a video camera, created shockingly direct femme fatale portraits (lead photo) that were projected onto the huge wall screen. The sheer intensity of these images equaled in effect Mr. Bogdan’s epileptic fit that came much later.

Mme. Stundyte, an extraordinary artist of magnetic presence, then disappeared under unfortunate wigs that greatly diminished her persona. Her murderer Rogoschin was played by Belarusian baritone Vladislav Sumlinsky, capturing the intensity of his obsession with an overtone of perverted Russian humanity.

Rogoschin’s rival to buy Natascha was the desperate Ganja, played in heroic voice by Slovakian tenor Pavol Breslik. Aglaja, Nataschia’s rival for the attention of the Idiot was well sung by Australian mezzo soprano Xenia Puskarz Thomas. Dostoevsky’s busybody, civil servant Lebedjew, who knew everyone and everything in Warlikowski’s generically stylized, modern Russian-esque world, was made into a fantastic joker/magician, the role gamely played by Ukrainian tenor Iuril Samoilov. Among other gold-plated casting was British bass Clive Bailey as Aglaja’s father.

The Salzburg Festival entrusted the staging of Prokofiev’s The Gambler to American wunderkind (now age 66) director Peter Sellars and his usual Salzburg associates, set designer/architect George Tsypin, lighting designer James F. ingalls, and costume designer Camille Assad.

Prokofiev greatly simplified and streamlined the plot of Dostoevsky’s The Gambler. The composer reduced its actors to the ten needed to achieve an operatic action. Director Sellars then turned the Dostoevsky nightmare into a quite breezy account of some nasty doings by some not very appealing characters. The opera was a few minutes more than two hours in length. Mercifully.

Of course Peter Sellars updated and politicized the happenings — cell phones and emails abounded, pro-environment protests, and surely even more moralizing beyond the opera’s hero (so-to-speak) Alexej’s condemnation of capitalism, and the world’s devotion to money. All this mattered very little as we were busy trying to keep up with the banter that moved the story along, getting us finally to the climax the evening — the absolutely spectacular roulette scene where Prokofiev added 15 additional solo voices to celebrate Alexei breaking the bank at the roulette tables.

[Polina, whom Alexei loves, then refused the 50,000 rubles offered by Alexei, the amount she had wanted to throw in the face of the Marquis, one of her debtor benefactors].

The roulette scene is a compositional tour de force by the young composer, building the excitement of spinning roulette wheels while interweaving the voices of the excited players, croupiers, onlookers, losers, etc., resulting in a musical orgy that finds the climatic colors and rhythmic excitement of the Stravinsky ballets for famed impresario Sergei Diaghilev that took stage in France during Prokofiev’s formative years.

[Diaghilev in fact met Prokofiev in London in 1915, commissioning the young composer to create a ballet, advising him to stick to Russian themes. The ballet Chout (The Buffoon) appeared in 1921].

Young (30 years) Russian conductor Timur Zangiev urged the Vienna Philharmonic and an ensemble of exceedingly well-rehearsed singers to a frenzy of musical excitement that equaled the light show unleashed on the stage by Sellars’ lighting designer James F. Ingalls, as the many, outsized spinning tops (roulette wheels) that were the riches everyone lacked, went airborne, whirling like flying saucers. Fog machines released clouds of vapor that shown dramatically in the lightning quick changes of full stage color.

Sellars’ set designer George Tsypin, besides creating the huge tops, opened up the galleries carved into the massive cliff behind the Rock Riding School stage, filling them with digital screens where we watched the audience (capitalists all) enter the theater, though he hung a heavy green covering over a few of the lower galleries so that there could be a space for scenes outside the casino. Intimate scenes were simply acted out down stage center in focused lighting.

[Though he may have lost Polina Alexej marveled mightily at the run of luck he had].

I’m not sure who the title gambler really was, maybe it was the debt ridden faux general, broadly acted and sung by Chinese bass Peixin Chen, whose rich grandmother was supposed to die but instead lost most of her fortune at the roulette wheel — played by Lithuanian mezzo soprano Violetta Urmana. Probably the gambler was the university student Alexej who had all attendant progressive attitudes, though he learned finally that money could not buy love, though it was thrilling to be a winner. American tenor Sean Panikkar made this foolish, love sick student quite real.

Polina, the General’s ward, had many transactional relationships — among them the faux Marquis and his accomplice Blanche, played respectively by French character tenor Juan Francisco Gatell and Ukrainian mezzo soprano Nicole Chirka, and the rich Brit Mr. Ashley played by Madagascar baritone Michael Arivony.

She, Alexej’s femme fatale, was played by brilliant Lithuanian soprano Asmik Gregorian (Castellucci’s Salzburg Salome, and Warlikowski’s Salzburg Chrysothemis). Possessed of magnetic personal presence, and of powerful, dramatic voice this unique artist was superfluous to this character, and to this production — she was not the promiscuous, teasing student, ensemble singer that director Sellars envisioned. Mme. Gregorian is a diva.

Michael Milenski

Der Idiot, Felsenreitschule, Salzburg Austria, August 11, 2024. Der Spieler, Felsenreitschule, Salzburg, Austria, August 12, 2024. Der Idiot photos copyright SF/Bernd Uhlig, Der Spieler photos copyright Ruth Walz, all photos courtesy of the Salzburg Festival.