This is one of three Leonardo Vinci recordings that I’ve had the privilege of reviewing in recent years. The other two were Siroe re di Persia (from the renowned Teatro San Carlo in Naples) and Gismondo re di Polonia (from an interesting early-music organization in Vienna, Parnassus Productions, and featuring the superb countertenor Max-Emanuel Cenčić).

This world-premiere recording of Didone abbandonata (from the 2017 Maggio Musicale Festival in Florence) is very much at the level of those two—both for what Vinci composed and for the skill with which it is put across.

As opera lovers may suspect from the work’s title, the libretto is based on a famous one by Pietro Metastasio that was set by dozens of other composers over the course of more than a century, including such notables as (in chronological order) Domenico Scarlatti, Albinoni, Galuppi, Hasse, Jommelli, and Paisiello. The libretto was one of Metastasio’s very first, written for the prolific opera composer Domenico Sarro in 1724. Two years later, Vinci set a version that was adapted for his purposes and for the singers in question by Metastasio himself. The first production of that opera took place in Rome. The women’s roles were sung by castrati because Church officials did not permit women to sing or act on the public stage.

Didone abbandonata is based on episodes from Ovid and Virgil. The basic plot is the anguished decision of Aeneas (in Italian: Enea) to leave Dido (Didone) and, at the gods’ behest, found a new city and empire on the Italian peninsula. The plot is thus, in its broad outlines, somewhat similar to the plot of Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas of a half-century earlier and to the last two acts of Berlioz’s Les Troyens, more than a century later. But the libretto is enriched by elements involving other characters. For example, the African king Iarbas (Iarba) is intent on gaining Dido’s affections and, after being rejected by her, destroys Carthage in the final scene. As for Dido’s sister Selene, she is, just as hopelessly, Dido’s rival for the affections of Aeneas.

Didone abbandonata was one of Vinci’s most highly praised operas at the time. Alas, the composer died in 1730, at the age of around 40. (For further details on the libretto and on Vinci’s opera, see the respective entries in the Grove Dictionary of Opera, a four-volume reference work whose entire contents is now available online, by subscription, or through many libraries, at www.OxfordMusicOnline.com.)

Nowadays, of course, we have no castrati, and are happy to see and hear women on stage. On this recording, most of the high-voiced roles, whether female or male, are taken by women. The African—or “Moorish”—king, Iarbas, is sung by a countertenor. The lowest voice in the opera is the one tenor role, that of Aeneas.

The music is very much like that of Handel’s and Vivaldi’s operas: a series of da capo arias separated by stretches of recitative. The orchestration is simpler than tends to be the case in Handel: oboes and brass instruments are used rarely, and then in a largely supportive role (such as to emphasize Iarbas’s military threats against Carthage—CD 3, track 5) rather than as attention-getting obbligato solo instruments.

The libretto is one of a very few by Metastasio to end tragically: Dido refuses to flee Carthage and dies in the fire. Vinci responds to Dido’s final speech with an effective accompanied recitative in which the powerful but now-isolated queen, rejected by her lover, alternates sorrowful arioso phrases and dramatic short outbursts, all punctuated by short incursions from the unison strings, such as dotted-note figures on a single pitch, and dramatic runs.

The singers on this recording have mostly firm, flexible voices enabling them to negotiate with ease the many coloratura passages. Their voices are different enough that, after a while, I was able to tell which singer is singing, even without looking at the libretto. I could always identify Selene because that singer is the only one with much wobble in her tone. Fortunately, the wobble gradually lessens as the opera advances, presumably because her voice has now warmed up.

My favorite of the six singers is Roberta Mameli, who brings glamor to the role of Dido (Didone). Mameli’s quick, tight vibrato nicely suggests Dido’s specialness, and also the power that she wields in Carthage. When Aeneas tells her, near the end of Act 1, that he is leaving her to found Rome, Mameli, as Dido, berates him impressively, yet without ever resorting to rant and noise. Countertenor Raffaele Pé matches Mameli in vocal skill and sensitive word-pointing, and he embellishes with great flair. I also enjoyed the rich-toned mezzo-soprano Marta Pluda in the role of Iarbas’s confidant Araspe. Carlo Allemano’s solid tenor conveys well Aeneas’s commanding personality and deep sense of duty to his gods-ordained mission. The small orchestra, under Carlo Ipata, plays skillfully and with varied pacing that never drags.

Good, clear booklet essay and plot summary, though lacking details about the version heard here, “revised” by the conductor. (Is it note-complete? Have any arias or recitatives been truncated or omitted?) The track list, confusingly, mentions only the first character who sings in each track. The libretto, in Italian and good English, can be downloaded here. The list of characters seems to have been drawn from the original printed libretto. It could have been expanded a bit to make clear that Osmida and Araspe, the respective advisors of Dido and Jarba, are men (that is, officials rather than, say handmaids or nurses). I mention this because neither name is obviously male (at least to my eye) and because the roles are here sung here by women; hence, I imagine, some other listeners, too, may be confused at first.

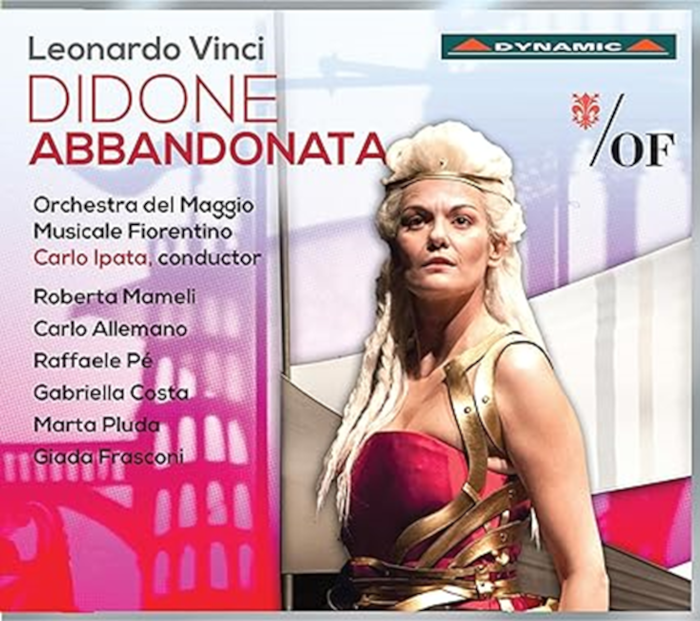

A few photos from the stage production plus a three-minute trailer, above, helped me greatly to imagine the action. The costumes, thankfully, were ancient-style (if somewhat stylized—indeed beautifully so), rather than, say, evoking some more specific recent situation, e.g., Napoleon (in Egypt), Mussolini’s troops (in Ethiopia), or any one of several authoritarian regimes making headlines today.

The singing and playing are captured with gratifying clarity (aside from a weird echo at the beginning of CD 3, track 7), and some sounds of on-stage action (e.g., sword-fighting) help one sense what is going on. The editors have preserved a small amount of applause yet managed to avoid capturing any distracting audience noise elsewhere. A DVD version has also been released; I suspect it makes for lively viewing, based on the vividness of the CD recording and the little bits shown in the three-minute trailer above.

All in all, this recording reflects the high standards for which the Maggio Musicale festival in Florence has long been known, and shows it extending them to unusual early repertory. It also indicates that Vinci, heretofore mostly a name in history books, was indeed a composer whose operas are worthy of being staged more frequently. With singers like Roberta Mameli, Vinci’s long-forgotten works are in marvelous hands.

And admirers of this major (but shortlived) Baroque composer will want to know that Haymarket Opera (Chicago) will be releasing a recording of his Artaserse (based on three performances in June-July 2025 that featured Metropolitan Opera tenor Eric Ferring and countertenor Key’mon Murrah).

Ralph P. Locke

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music and Senior Editor of the Eastman Studies in Music book series (University of Rochester Press), which has published over 200 titles over the past thirty years. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, The Boston Musical Intelligencer, and Classical Voice North America (the journal of the Music Critics Association of North America). His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and is included here, lightly revised, by kind permission.

Leonardo Vinci, Didone abbandonata (World-Premiere Recording)

Roberta Mameli (Didone), Carlo Allemano (Enea), Raffaele Pé (Iarba), Gabriella Costa (Selene), Marta Pluda (Araspe), Giada Frasconi (Osmida).

Florence Maggio Musicale Orchestra, cond. Carlo Ipata.

Dynamic 7788 [3 CDs] 160 minutes.

Click to buy or explore any track.

Top image: The Death of Dido by Joseph Stallaert (Source: WikiArt)