San Francisco Opera unveiled a handsome new production of Parsifal just now — new productions a fairly rare occurrence at SFO.

More importantly this Parsifal continues San Francisco Opera’s music director Eun Sun Kim’s exploration of the operas of Verdi and Wagner — the absolute core repertory. San Francisco Opera just announced that the maestra will conduct Wagner’s Ring in spring 2028 in the third San Francisco go-around of the Francesca Zambello 2011 production. Where is the excellent Achim Fryer LA Opera 2010 production when we need it?

San Francisco Opera Orchestra’s brass choir sang in magnificent, pure and clear Parsifalian tone (I was seated house right where the horns, trumpets, trombones and the Wagner tuba were concentrated — just where you would want to be!). Conductor Kim respected Wagner’s first act as a grandiose rhetorical statement, fragmenting its musical elements, punctuating it with moments of silence, thus depriving the act of its dramatic crescendo to the revelation of the Holy Grail (an outsized, golden chalice).

Act II, Klingsor’s garden, found the maestra in her element — big music, big voices, big happenings. Well, until the Parsifal, Brandon Jovanovich, ran into vocal difficulties, leaving us bereft of a strong male voice for his heroically conducted battle of wills with Kundry. Conductor Kim easily achieved Wagner’s sublimity in Act III, effecting the solemnity of Amfortas’ redemption and Parsifal’s purification in the huge gestures and volumes that define her musical ethos.

The production designer for the new Parsifal was Robert Innes Hopkins, a British designer whose credits include the 2012 San Francisco Opera Lohengrin, the 2024 Tristan (plus the generic 2018 Tosca), and the recent Lyric Opera of Chicago Ring cycle. This Parsifal was two concentric revolving stages moving in opposite directions (a spectacular effect), myriad drops of trees, gothic arches, and a forrest of strung-up, upside down dead warriors. There were some walls as well. It was an heroic setting, speaking to the monumental philosophic, if poetic, discussions inherent to Parsifal.

The assumption is that this new Parsifal is a legacy production, meant to serve different stage directors in different ways over the coming years.

The show curtain (a drop replacing the grand, gold stage curtain) seemed to be in a different aesthetic world. Its image was a Day-Glo orange elongated triangle, hinting at Masonic principles maybe, though that triangle would be unilateral. Los Angeles born stage director Matthew Ozawa, now the Chief Artistic Officer at Lyric Opera of Chicago, resurrected the artistic team he assembled for his 2022 San Francisco Opera Orfeo ed Euridice, Gluck’s remake of Baroque opera into new, ultra simple terms.

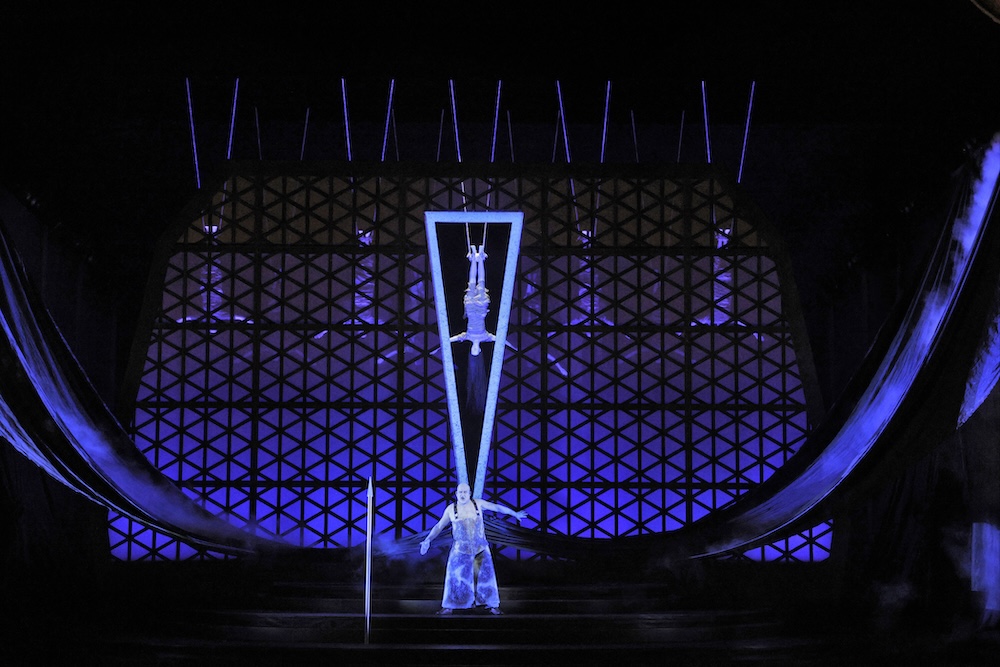

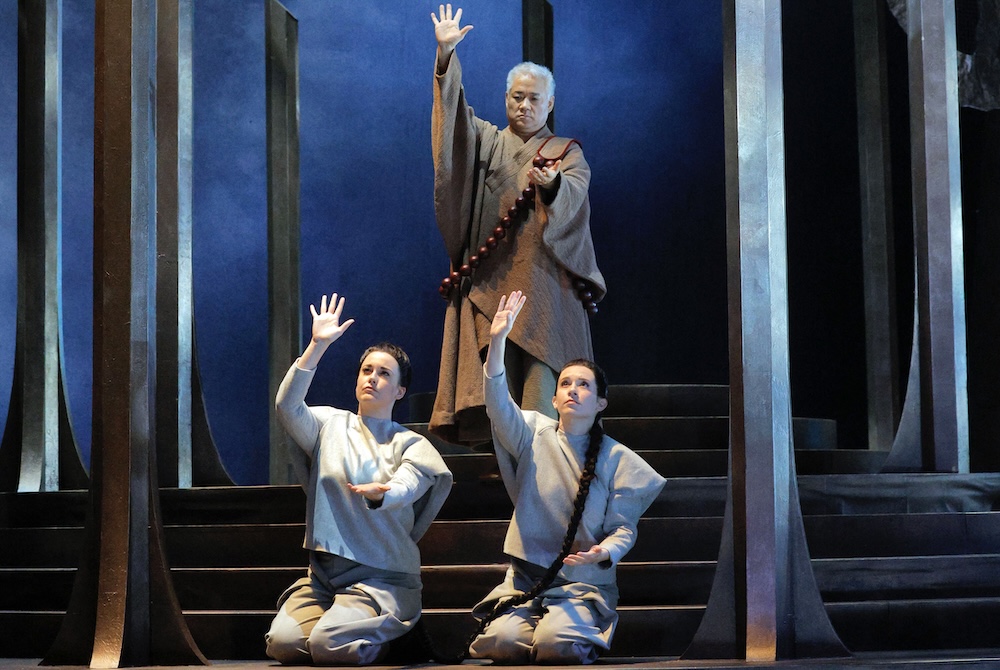

Mr. Ozawa’s Parsifal had abundant triangles indeed — the three, red clad, dancing guardians of the grail were a tall male flanked on either side by shorter females making an upward pointing human triangle; Klingsor had two black wings soaring upward on either side, making an inverted triangle; Klingsor’s garden was bedeviled by fallen warriors each suspended by two outward soaring ropes. There were many more upward and downwards pointing triangles in all the scenes.

Mr. Ozawa was said to have embellished in his Parsifal his Orfeo ed Euridice meditation on grief and renewal, adding spiritual yearning and redemption. Left unsaid was Mr. Ozawa’s purging Parsifal of its overload of philosophic, psychological and poetic meanings that render it open to myriad interpretations. As it was, the Ozawa simplification robbed the first act of any dramatic intensity, sabotaging conductor Kim’s musical exposition.

Like Orfeo ed Euridice, Mr. Ozawa embellished Parsifal with modern dance. Chicago based choreographer Rena Butler filled in all purely orchestral moments with interpretive dance movement, obliterating Wagner’s use of music alone to evoke the sublimity of spiritual stasis. Though, to fine effect, Mme. Butler added a Kundry dancer double (identically dressed with identical long black wig). It seemed superfluous and forced in Act I, but in Act II the double was used to brilliant effect, enriching the Parsifal Kundry stand-off with explicable sensual overtones, adding Parsifal himself into the choreography, Mr. Jovanovich is known to be game for almost anything.

N.B. The dancer I perceived to be the Kundry double was actually Parsifal’s mother in this production.

The costumes, designed by Jessica Jahn, found the Day-Glo aesthetic with costumes that responded to Mr. Ozawa’s streamlined version of Parsifal. Amfortas was outfitted with a weird, grandiose white collar, the Knights of the Holy Grail had a vaguely fascistic, futuristic look. The maidens of Klingsor’s garden were gowned so that their dress changed color as they moved about the stage, such virtuosic lighting was the work of Japan born designer Yuki Nakase Link. The spectacular lighting effects included bringing the War Memorial Opera House’s proscenium arch to a golden glow as the grail sat on its pillar in the final moments of the opera, though here, in the opera’s most sublime moment, the red clad dancer triangle was still in interpretive movement.

Tenor Brandon Jovanovich was Parsifal, a role he performed at the Salzburg Festival in 2022. He is a fine artist, and actor, though at the performance I attended (November 13) he succumbed to vocal problems — though never losing, at 55 years of age, Parsifal’s boyish swagger. Kundry was sung by Swiss mezzo soprano Tanja Ariane Baumgartner who upcoming will sing Herodias [!] in Salome at Lyric Opera of Chicago. She performs the important Wagner mezzo-soprano roles on Europe’s major stages. Of beautiful, darkly colored voice she brought diva fireworks to her Act II confrontation with Parsifal, and submissively washed his feet in Act III, biblical reference trumping sexual politics.

Gurnemanz was sung by Korean bass Kwangchul Youn in rich tone, dispassionately telling us what we need to know — it was indeed pleasurable listening to his lengthy narrations, and even more pleasurable when in Act III Mr. Youn’s Gurnemanz actually showed incredulity, joy and relief as he learned that Parsifal is not a fool after all, that the spear Parsifal is offering is the one that pierced Christ’s side. Amfortas was sung by Brian Mulligan in glorious golden tones you might term tenorial. Mr. Mulligan does not possess the gravitas of voice or persona usually associated with the wounded guardian of the Holy Grail. Mr. Mulligan will be the Wotan for the 2028 San Francisco Opera Ring.

Klingsor was sung by German bass-baritone Falk Struckmann, the Alberich in the 2018 Ring. Of gruff voice and persona he easily personified a simple brutality that imprisoned Kundry and wounded Amfortas, streamlining his complex role in Wagner’s sprawling epic poem.

Of note were the six flower maidens of Klingsor’s garden who held forth with resolute confidence, and the two squires in Act I, tied together by their shared braid, surely for some reason, and the first two knights who were somehow connected as well. These myriad smaller roles were largely staffed by current and former Adler Fellows (San Francisco Opera’s young artist program). Credit must be given as well to the San Francisco Opera corps de ballet, which fulfilled its considerable role in this production with remarkable dancerly finesse.

Michael Milenski

War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, California, November 13, 2025

All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera