One bright morning in mid-February 1919, a crowd of a million people gathered in New York to welcome home the 15th Infantry Regiment of New York’s National Guard, who had fought in France as the 369th Infantry Regiment of the American Expeditionary Force. The 369th had survived 191 days under enemy fire without losing a single prisoner or a foot of ground; they received the Croix de Guerre for their bravery, though losses were high and casualties severe. The old 15th was unusual in that, excepting its officers, the regiment was made up entirely of black Americans.

Among the men who received a hero’s welcome was one Lieutenant James Reese Europe – a 39-year-old composer, dance-bandleader and, more recently, machine-gun company office – who marched at the front of his world-famous 369th ‘Hellfighters’ Band. Born in Alabama in 1880, James Reese Europe had built a stellar career as a musician and bandleader, and before the war had become one of the most influential musicians in New York, renowned as a composer and conductor of popular songs, dances, marches – music which he took with him to Europe in 1918, giving the continent its first taste of ragtime and jazz.[1]

In 1918, in neighbouring, neutral Switzerland, Igor Stravinsky and the Swiss poet and writer Charles Ferdinand Ramuz were sitting out the war, watching creative opportunities diminish and royalties dry up. Their response to their cultural isolation – and in Stravinsky’s case, spiritual isolation too, as an expatriate Russian for whom the Bolshevik Revolution had made a return home impossible – was to write a work expedient to their circumstances. That work was The Soldier’s Tale, a theatre piece designed to ‘be read, played, and danced’ by three actors, a dancer and seven instrumentalists, based upon a tale by the nineteenth-century Russian folklorist Alexander Afanasyev.

The first performance, funded by the Swiss businessman and amateur clarinetist Werner Reinhart, was given in Lausanne in November 1919, in a reduced form for violin, clarinet and piano; there were plans to tour the work, but these were derailed by the Spanish flu pandemic. One of the most striking aspects of The Soldier’s Tale is its interjection of modern dance music – waltzes, marches, tangos and ragtime – in a Russian musical idiom, a cultural dialogue which was reflected in other works by Stravinsky at this time, such as the short chamber piece Ragtime and the Piano Rag Music. One might see the intrusion of modern dances into the Russian fairy tale as a reflection of Stravinsky’s own alienation from his homeland at this time.

Directors Annabel Arden and Femi Elufowoju jr were inspired by these overlaps and coincidences – both historical and between the past and our own present time – during their collaboration on the Hallé’s new film of The Soldier’s Tale, which marks the fiftieth anniversary of Stravinsky’s death. Arden describes her ‘encounter’ with James Reese Europe as serendipitous – a family member happened to be making a documentary film about him – and the co-directors have alluded to Europe’s story as ‘a way to bring the figure of Stravinsky’s soldier closer to audiences today, whilst at the same time honouring a remarkable piece of black history’. This film is, Arden tells us, a ‘homage to many black soldiers who fought [in WW1], and subsequent wars, who have been forgotten or erased from the history of soldiering.’

The allusive touch is light, though; a slight tint in the visual frame. Ramuz’ narrative is respected. A violin-playing soldier returning home for a period of leave, encounter the Devil, who offers him a book with the promise of unlimited riches in exchange for the soldier’s violin. The soldier agrees to the swap and accompanies the devil to learn about the book and to teach him the violin. But, three days later, when he returns home he finds that three years have passed. To friends and family, he is a dead, a haunting presence to be ignored or feared. He follows the Devil’s guidance and gains great wealth, but realises that, in having everything, he has nothing. A princess’s illness prompts him to ‘win’ back his poverty in a game of cards with the Devil, and re-armed with his violin, he proffers a musical cure to gain the princess’s hand in marriage. But, when his new bride urges him to return to his home village and seek out his mother, his fate is sealed. The devil is waiting …

The Soldier’s Tale is a parable for its time but in its emphasis on exile, frontiers, uncertainty, and the suspension of time, it is also a tale for our own day. Moreover, the need that Stravinsky and Ramuz faced, to create an adaptable work that could be performed in reduced circumstances, with minimal scenery and by few performers, has been shared by all creative artists during the past year. Arden and Elufowoju’s film presents the seven musicians of the Hallé in a dust-sheet strewn space at the Bridgewater Hall. Shots of the musicians are interspersed between location scenes set in the heart of Manchester. The Soldier strolls homewards alongside the city’s canals. He laments his isolation against a night-time panorama, viewed from the top of Q-Park First Street car-park: bright lights against the inky sky; car-striped streets; tracks and trams and trains. The Soldier learns of the Princess’s illness and his own route to love and liberation while sitting outside ‘The Pev’ – that well-known urban drinkery, ‘The Peverill of the Peak’. The diabolical card game to win back the Soldier’s poverty, freedom and fiddle takes place in the shadowy under-croft of the Bridgewater Hall. The cameras move in close; the characters at times direct their confessions to the unseen watchers. The Narrator intrudes on private moments, prompts and coerces, judges and forgives. The result is a disassociation of narration, action and music which somehow both alienates and assimilates.

Richard Katz is a well-known presence on the stages of the RSC, Old Vic and Shakespeare’s Globe and, as our guiding Narrator, he relishes the springy rhymed tetrameter of Jeremy Sams’ translation. But, he’s worked a lot too with Complicite and he brings an energetic frisson to his storytelling, truly connecting with the audience he can’t see as, a scruffy but cocksure figure in baseball cap and casuals, he intrudes on the Soldier’s reflections and deliberations. The Devil’s book foretells the future, turning prophecies and promises into potent profits; but, our Narrator, too, knows how the story ends, and Katz reveals a exclamatory flair worthy of Andersen and a wry knowingness that Perrault would admire. “If you lose, you’ll win,” he urges, as the Soldier deliberates gambling all; he pulls his chair up to the table, an avid voyeur, even though he knows the way the cards will be dealt.

We can empathise with Martins Imhangbe’s flaws and desires. Our Soldier marches home with a blasé spring in his swaggering step, knapsack dangling from his broad shoulders. The city’s canals seem to welcome him, and guide him homewards, but the Devil lurks on bridges, down alleyways, and in underpasses. When he finally arrives at his destination and the members of his family – the Hallé musicians – do not register his ghostly presence, his anger is flung at the camera in a crude prose disrupted by pain and grief.

Stravinsky and Ramuz do indeed give the Devil all the best ‘tunes’. It’s a terrific role and Martin Lockyer chills with terrifying darkness. Whether smartly dressed in cashmere coat; vulgarly extrovert in drag, all lurid lipstick and doll-like wig, dragging a tawdry suitcase; donning an officer’s cap and pseudo-Nazi moustache; or swigging vino with the ostentatious exultation of the most deluded down-and-out, Lockyer exudes both hatred and self-disgust. “Card after card, hearts all the way, you probably think it’s your lucky day …” he drawls and drools.

He milks both the sing-song flippancy and elongated whininess of the rhymes. When the Soldier asserts that he must get along home to his mother, our Devil sneers, “She’ll have to wait a few days more/ Isn’t that what a mother’s for?”, the assonant elongations dripping with scorn. The rebuttal, “But, my darling’s pining yonder”, prompts only the sickly rejoinder, “Well, absence makes the heart grow fonder.” Lockyer’s Devil is a bully and a bore: abusive and patronising, facetious and exasperated. As the Soldier leaves through his book, “Treat it with the proper care,” he instructs, with eyebrows, cheekbones and leering lips seemingly alive, “it might make you a millionaire.”

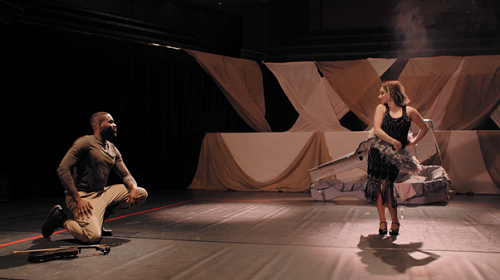

The Princess convalesces in a double bass case amid the dust sheets. Faith Prendergast is lured from her languor by violinist Peter Liang’s lithe solo tango: she rolls across the floor, clutching at her silk pillow, but is lifted by the more playful strains of the waltz and liberated by the ragtime, swapping pink pyjamas for a sequined black flapper’s frock and grey feather boa. She perfumes herself with champagne and hooks the Soldier into her dancing display, with glamour and grace.

The Hallé musicians confirm that rigour and control are required to conjure recklessness and confusion. From the first springs of the Soldier’s brassy march home to the final percussive death knells that mark his doom, the rhythms are taut, colours are vivid, the threat of temporal chaos is kept at bay by discipline and virtuosity. Liang digs richly, and with a bristly staccato, into the double-stops that bring the violin to life. Sergio Castelló López (clarinet), Emily Hultmark (bassoon) and Gareth Small (trumpet) inject some wistfulness and whimsey, especially in the ‘Pastorale’ following the Soldier’s rejection, their nostalgic reminiscences perched above eerie double bass harmonics (Billy Cole). They make the music both highly charged and hopelessly hollow, donning gold party hats for the ‘March Royale’ and adopting an ironic poise for all the music’s vulgar exuberance. The ‘Little Concert’ has a manic circling obsessiveness that belies the supposed defeat of the Devil: clean and crisp, it’s like a nightmare circus-ride from which one can’t escape. And, throughout all, Sir Mark Elder is the embodiment of understated precision and directness.

At the close, it comes down to a bullfight between a Devil who’s thrown his deck of cards into the canal and a Soldier who wields his violin like a matador’s cloak, his violin bow his muleta. As the characters recede into myth, the Narrator reports their words. In the final ‘Triumphal March’, the air of desperation deepens as the Devil taunts the Soldier with his violin, around the Hall, alongside the waterways. Onto the canal-side cobbles falls a monochrome photograph: the face of James Reese Europe, stabbed and murdered in 1919 by a former band-member, stares from the creased square. Back in the Bridgewater Hall, the Devil has one more tune up his sleeve …

The Hallé’s film of The Soldier’s Tale is available (£) until Thursday 29th July 2021.

Claire Seymour

Stravinsky: The Soldier’s Tale

Richard Katz (Narrator), Martins Imhangbe (Soldier), Mark Lockyer (Devil), Faith Prendergast, (Princess); Annabel Arden (Director), Femi Elufowoju jr (Co-Director), Dominic Best (Film Director), Gemma Dixon (Film Producer), George Johnson-Leigh (Designer)

The Hallé: Sir Mark Elder (conductor), Peter Liang (violin), Billy Cole (double bass), Sergio Castelló López (clarinet), Emily Hultmark (bassoon), Gareth Small (trumpet), Katy Jones (trombone), David Hext (percussion)

Streamed on Thursday 29th April 2021.

ABOVE: Martin Lockyer (Devil)

[1] Having survived the war, Europe died just a year later, in 1919, when he was stabbed by a former bandmember. See, Badger, R. (1995) A life in ragtime: a biography of James Reese Europe, New York: Oxford University Press.