A ponderous reading of the Strauss score, a meticulous, methodical staging of the Oscar Wilde drama. A radiant Salome, an unleashed Herod. Unsettling, sentient scenography. Unexpected magnificence.

High, very high Teutonic art unfolded under the gentle breezes of a cloudless Provençal sky. Shocking, blasphemous imagery — Jochanaan’s severed head on a serving platter at a replication of Da Vinci’s Last Supper, a crucified Herodias — appeared on the flat screen face of a very defined, very contained stage box, like the black and white moving images of primitive expressionistic film, but now widescreen, with the evolving shades of the alabaster skin of John the Baptist and Jochanaan’s black hair.

Conductor Ingo Metzmacher brought the 109 players in the pit of Aix’s Grand Théâtre de Provence (the Orchestra de Paris) to monumental volumes, molded into sumptuous harmonies when not raging and pleading in carefully delineated and paced blocks. Blocks created by venerable German stage director Andrea Breth to slowly and carefully enshrine the nascent, sick, very sick sexuality of the adolescent Salome, and the consummation of her desire. Blocks created by the settings of Austrian scenographer Raimund Orfeo Voigt that moved onto and out of a black floor that heaved with guilty rage and desire under an unsettled, nervous moon.

Within this, and in fact its maker was the unlikely Salome of Franco/Danish lyric soprano Elsa Dreisig, not-so-long-ago an Aix Micaela. If initially she was overwhelmed by the massive symphonic noise, by the time she consummated her desire — this in a white tiled bathroom/interrogation room/isolation cell — she attained a beautiful steely, silvery volume. Tones that sailed easily through the now solemnly beautiful orchestral sounds of fulfillment, when not assailed by the intrusion of Strauss’ nauseous dissonance.

Finally, the crushed Salome curled herself into a fetal position in the corner of her cell, and the hidden voice of Herod shouted needlessly for her slaughter. Salome’s death had been presaged in her dance — her psyche, the stage floor as it happened, was in full eruption. Four identical Salomes slowly, butoh-like, moved through a complex dream of inexorable emotional conflict.

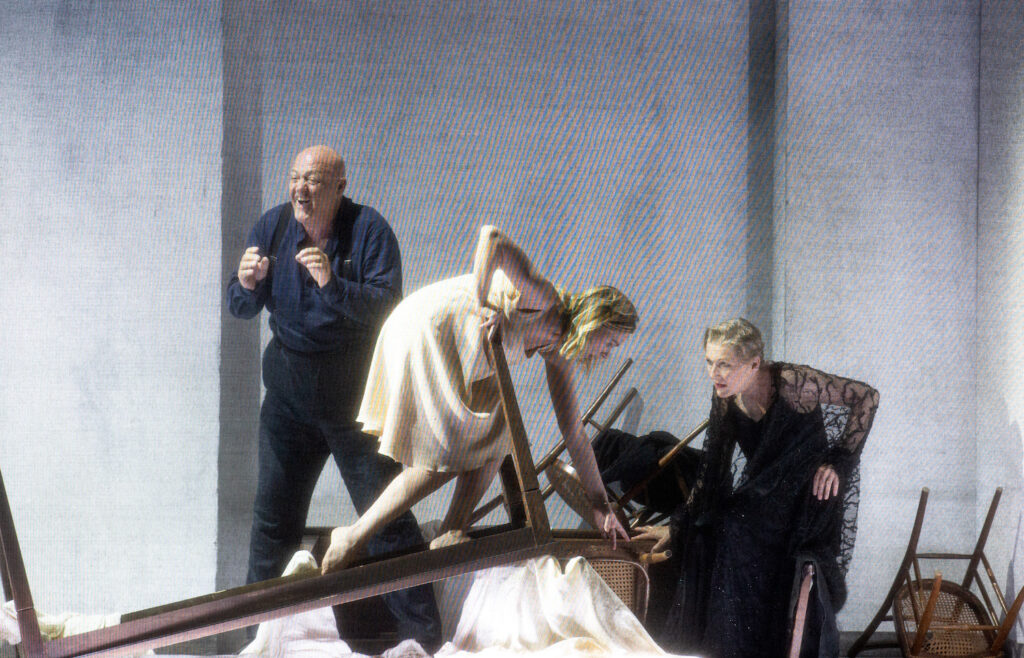

British tenor Jonn Daszak, known to Aix audience through Andrea Breth’s hyper expressionist staging of Wolfgang Rihm’s Jacob Lenz (2019), was at once a protagonist and antagonist to Salome’s psyche. He shrilly dominated his operatic banquet — in fact Salome’s last supper, the Jews to his right erupting into hugely monumental discord, the Nazarenes on his left voicing miracles and salvation.

But the mise en scène, sentient to itself, had had enough. Director Andrea Breth simply stopped it all. We sat at a silent, still tableau `— a mute thunderclap — for the eternity of maybe only a few seconds. Strauss be damned.

The banquet continued. Herodias, enacted by soprano Angela Denoke, herself a famed, not-so-long-ago Paris Salome, echoed her daughter’s doubts and resolves, and in fact became one with her daughter.

The first voice we hear in Salome is that of Narraboth extolling the beauty of Salome and the beauty of the moon. Like the Salome of Elsa Dreisig, Spanish/Porto Rican tenor Joel Prieto is of beautiful, light lyric voice. He was the voice of a youthful innocence awakening to the forbidden desires of the world. He suicides, this innocence slipping into the precise chasm in the stages’s sentient floor where Salome, is confronting Narraboth, obsessed by horror of the Prophet’s body, and awakened to the horrors of her mother.

Jochanaan was sung by Hungarian bass baritone Gábor Bretz, a voice of enormous authority whose words were heard first everywhere in the stage box, then from random placements on Herod’s terrace, that was, as well, Salome’s emotional floor. Jochanaan’s severed, singing head was previewed on the table at Herod’s banquet table (Narraboth’s head on the floor beneath his feet) where Herodias shouted for its silence, and where the beaten Herod finally consented to the horror of Salome’s demand.

An extended, thunderous timpani roar, in an imposed fermata, brought the head of Jochanaan to Salome. The head was now hidden, and unseen, in a tin washtub. Strauss be damned.

Casting at Pierre Audi’s Aix Festival continues to be one of its greatest glories, these singers, and the impeccably cast Jews and Nazarenes, fully embodied stage director Andrea Breth’s blatantly Freudian world. It was a world brilliantly concocted scenically by designer Voigt, strikingly and remarkably subtly lighted by Alexander Kopelmann, and faultlessly executed by the Festival’s technical staff. Costumes, by Alexandra Charles, were based in the filmic early twentieth century.

Mr. Audi fearlessly confronted the fame of the recent Salzburg Festival Romeo Castelucci Salome with his own Salome. Worlds apart in the universal and particular these two productions will remain operatic benchmark productions for years to come.

Michael Milenski

FESTIVAL D’AIX EN PROVENCE 2022 SALOME DIRECTION MUSICALE: Ingo Metzmacher MISE EN SCÈNE: Andrea Breth DÉCORS: Raimund Orfeo Voigt COSTÜMES: Carla Teti LUMIÈRE: Alexander Koppelmann CHORÉGRAPHIE: Beate Vollack Salome Elsa Dreisig Jochanaan Gábor Bretz Herodes John Daszak Herodias Angela Denoke Narraboth Joel Prieto Ein Page der Herodias Carolyn Sproule Erster Jude Léo Vermot-Desroches Zweiter Jude Kristofer Lundin Dritter Jude Rodolphe Briand Vierter Jude Grégoire Mour Fünfter Jude / Zweiter Soldat Sulkhan Jaiani Erster Nazarener / Ein Kappadozier Kristján Jóhannesson Zweiter Nazarener Philippe-Nicolas Martin Erster Soldat Allen Boxer Eine Sklavin Katharina Bierweiler Danseuses et danseurs Martina Consoli Beatriz De Oliveira Scabora Jacqueline Lopez Alessia Rizzi