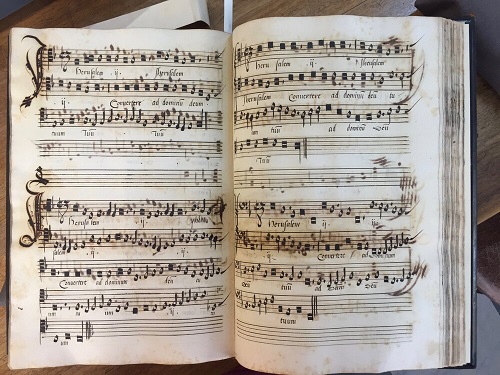

Musica Secreta’s co-director, Laurie Stras, relishes an archival detective hunt. The ensemble’s 2019 recording, From Darkness into Light, presented the fruits of Stras’s discovery of what she described as ‘seventeen verses, which were found hiding in plain sight in a sixteenth-century manuscript’, that revealed Antonine Brumel’s setting of the Lamentations of Jeremiah to be much more magisterial and elaborate than had previously been imagined. The disc also included items – some anonymous compositions and others by masters such as Josquin and Antonio Moro – from a leather-bound Florentine manuscript dating from 1560, known as the Biffoli-Sostengi manuscript, after two nuns, Suor Agnoleta Biffoli and Suor Clemenzia Sostegni, whose names are embossed in the binding and whose familial heraldic emblems are prominent in the illuminations.

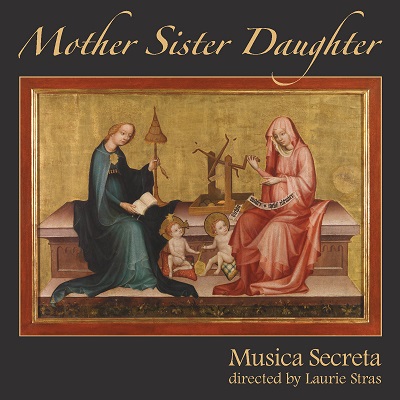

Now preserved as MS 27766 in the Library of the Royal Conservatory in Brussels, the Biffoli-Sostengi manuscript reveals much about the daily lives of the convent in which it was used as a conduit of devotional observance. It contains both plainchant and polyphonic cantus firmus works, and the diversity of hymns, psalms and falsobordone psalm settings, antiphons, masses and prayers which serve the eight Hours of Divine Office, confirms the significance that music played in the nuns’ lives. The nuns’ relationships, with their families, with God, with each other, were modelled on the life of the Virgin Mary, the musical honouring of Christ’s mother and God’s daughter enhancing the spiritual growth of her ‘sisters’. But, to which convent did the Biffoli-Sostegni manuscript belong? This was the riddle that Stras set out to solve – and the answer to which is presented in Musica Secreta’s latest recording, Mother, Sister, Daughter.

While the liturgy for each day was proscribed by the breviary adopted by a convent’s Order, the ‘proper’ was more flexible; on the feast days of individual saints, for example, it might tell that saint’s story, especially in the case of the feasts celebrating the founder or patron saint of the Order, which offered an opportunity for the sisters to reflect on their emotional and spiritual connection to the saint in question, and how this relationship was reflected in their daily lives. The Biffoli-Sostegni manuscript contains repertoire that points to a Clarissan context – most specifically the groups of antiphons and hymns for the Feast of St Clare, including a Lauds and two Vespers settings, propers that are not derived from the Breviarum romanum, but from the thirteenth-century rhymed office of St Clare.

Stras thus narrowed down the potential Florentine convents which housed the Biffoli-Sostegni manuscript to two: the wealthy San Jacopo in Via Ghibellina in the centre of Florence, and a poorer convent, San Matteo, in Arcetri, about a mile south of the city walls. Initially, she assumed that the former would provide the evidence to link up the parts of the puzzle; but, it was in San Matteo’s records that the names of Biffoli and Sostegni could be found, along with the dates they entered the convent, their dowries, and other information about their families and lives.

What made this finding even more exciting was that San Matteo had been the home of Suor Maria Celeste – the illegitimate daughter of Galileo Galilei, born Virginia Galilei (‘Celeste’ in recognition of her father’s astronomical research) – who entered the convent in 1613, aged thirteen, and was joined in the strict Clarissan Order by her sister, Arcangela. Her father described Suor Maria Celeste as ‘a woman of exquisite mind, singular goodness, and most tenderly attached to me’ and the 124 extant letters that she wrote to her father between 1623-34 reveal the close relationship that she maintained with Galileo, who came from a family of talented musicians: Virginia’s uncle and brother were renowned lutenists, while Galileo’s father was the influential composer-theorist Vincenzo Galilei.

Celeste’s primary roles at the convent were as apothecary, confectioner and financial administrator, and most of the letters concern mundane domestic matters and matters relating to the life of absolute poverty that was required by the Order. But, towards the end of her life, Suor Marie Celeste was asked to teach plainchant and supervise the daily office in the choir. She wrote to her father, ‘it is true that I would enjoy these duties greatly, were I also not obliged to work’, joking too about the need to brush up her Latin. Occasionally she asked her father to send her music, such as organ ricercars (there were three organists at the convent).

The two Vespers for the Feast of St Clare, containing polyphonic antiphons and composed for four very high voices, were performed over two days and must have been the high point of San Matteo’s liturgical year. Musica Secreta have recorded them with the chant antiphon and the doxology, to offer contrast to the consistently high register of the four shimmering voices, but also, in Stras’s words, ‘to give the modern ear a flavour of how they would have sounded to the nuns and their families, gathered in the external church listening to their daughters on the other side of the grille’. And, it’s worth remembering that performing music was one way in which the architectural and spiritual spaces of the convent could be opened up, allowing the sisters to sustain familial, social and spiritual relationships.

“Now, with the brightness of Saint Clare the world’s structure with splendour is wonderfully completed” declare the four voices at the start of the First Vespers, like rays of light of different but blended hues. The psalm antiphons glow with calm joy as they tell of Clare’s spiritual devotion, her studies with Francis, “her marriage to the King of Kings” and beatification. At times the tessitura opens up, unwinding and separating the individual voices, which then come together in perfect unison in the chants. Always the music flows with comforting serenity.

The Second Vespers introduce Clare’s sister, Agnes, who witnesses Clare’s spiritual passage and who, in death, follows her into heaven. The Magnificat which closes the Second Vespers, “Salve sponsa Dei”, hails the bride of God with sumptuous colours and makes use of the ancient practice of extemporised counterpoint which results in striking parallel motion and harmonic richness. One can imagine how moving it must have been for the Galilei sisters, and also for Agnoleta Biffoli and her sister Caterina who followed her into San Matteo, to sing praise to their founding sister, “Pure virgin, our guardian” and call upon “the predecessor of the body of sisters” to lead them up to the heavenly realm, the music confirming bonds of blood and faith.

Mother, Sister, Daughter also presents works from manuscripts in the Biblioteca Capitolare in Verona dating from c.1495 and c.1480. Heraldic illuminations suggest that Verona 761 may have been prepared to commemorate the wedding of Isabetta Brenzoni and Giorgio Maffei in 1495, and it’s been posited that the portrait of a nun on the opening page, above a miniature of a group of novices around a lectern singing from a choir-book, is of Brenzoni herself, who was abbess of the Benedictine convent Santa Lucia sopra il Chievo from 1492 to 1511. In the Kyrie and Gloria of Missa de Beata Virgine, following Florentine practice, the voicesare supplemented by organ, bass viol and harp which adds density and texture, although there is a prevailing freshness and freedom. The antiphons of the Vespers of St Lucy come from Verona 759 and tell of another sisterly bond, as St Lucy prays to St Agatha to cure her mother’s illness, and receives a reply assuring her that she has the power to do this herself. The alternation of small vocal forces creates a simple but direct narrative, the homophonic voices coming together sonorously in the Magnificat, ‘Tanto pondere’.

Various motets and prayers weave together the stories of women from the past. Ave mater matris Dei (attributed to Jean Mouton) is found in the Vatican’s Palatini part-books, thought to have been presented to Queen Anne of Hungary (1503-47) by Margaret of Austria, regent of the Netherlands (1480-1530), who was an important musical patron. The three vocal lines unfold with gentle sweetness, praising St Anne, mother of the Virgin Mary. Maistre Jhan’s Ecce amica mea sets text from the Song of Songs, but rather than presenting the man gazing at his lover through the trellis, it is she who “stands behind our wall, looking through the windows, showing herself through the lattice”.

This rich, harmonically elaborate motet for six voices is thought to have been presented to Suor Leonora d’Este (1515-75), daughter of Lucrezia Borgia. Suor Leonora was herself a talented musician and two works for five voices which were published anonymously but are attributed to her are included here – the bright, spirited Vespere autem sabbati which tells of the visit of Mary Magalene and Mary Salome to Christ’s tomb on Easter morning, and Virgo Maria speciossisima, an intricate Marian prayer which quotes the opening phrase from Antoine Brumel’s Mater patris et filia, which precedes it here. Mater Christi cooperto capite (attributed to Juan Anchieta) is particularly lovely. The original motet text, Rex autem David, is altered, substituting ‘Mater Christi’ and ‘Jesu Christi’ for ‘David’ and ‘Absalon’, and mezzo-soprano Katharine Hawnt and Kirsty Whately, playing a double harp, present a poignant portrait of maternal grief.

Two, free, additional tracks – in vernacular languages and composed by dissenting women – are offered online. In the spiritual song Avès poinct veu la malheureuse (sung to the tune of Avès poinct veu la peronnelle?’),prolific poet and composer Marguerite of Navarre (1492-1549) warns against embracing melancholia and rejecting God’s grace. In the verses selected here from the original forty-one, mezzo-soprano Victoria Couper and viol-player Alison Kinder tell of the music of the nightingale, lark, starling, jay and magpie which is silenced by the unhappy girl’s misery, replaced by foxes and bats who, hearing her sad weeping, “take more pleasure than in her laugh”. In Aen mijn Suster Martha Baerts (d.1650) reaches out to her spiritual sister, Betken van den Houte, who was beheaded in 1560 for her Anabaptist beliefs, alongside her maid. Soprano Hannah Ely and organist Claire Williams capture the quiet intensity of this emotive spiritual song.

These musical stories of women from the past weave a web of relationships that, in the final work on the disc, extends into and entwines with the present. Joanna Marsh’s The Veiled Sisters for six female voices, organ and viol, which was commissioned for the recording, sets two texts: ‘Half-Sister’ (2005) by the Norfolk poet Esther Morgan, which conveys the thoughts and feelings of a reclusive woman who watches from her darkened house as her half-sister blossoms in the sun’s warmth; and a seventeenth-century sonnet by the Bolognese poet Alessandro Francucci which honours a singer, Erminia Abelli, as she leaves behind the secular world and enters the spiritual realm of a convent. The juxtaposition of different experiences of veiled womanhood, of sunshine and shadow, singing and silence, is potently exploited by Marsh.

The Veiled Sisters closes with images of seclusion and spiritual rapture:

Here in flames of love she turns her heart,

and with sweet singing puts into oblivion

human worries, an makes the cloisters

into a paradise.

Shortly after Galilei Galileo returned to Arcetri in disgrace, sentenced to house arrest and forced to recant his views on heliocentrism, Maria Celeste died, at the age of 34. Almost 100 years after his own death, when Galileo’s remains were exhumed and moved to a tomb near the entrance of the Franciscan church of Santa Croce in Florence, two skeletons were found in his grave. The second was identified as that of a woman, who had died young. Even today, there is no inscription on the tomb to indicate the presence of Virginia Galilei beside her father in the grave. But, Mother, Sister, Daughter allows women such as Suor Maria Celeste to tell stories of their own and others’ lives, and creates a community of female voices, connecting past and present.

Claire Seymour

Mother, Sister, Daughter

Musica Secreta: Laurie Stras (director), Yvonne Eddy, Hannah Ely, Victoria Meteyard (sopranos), Victoria Couper, Katharine Hawnt (mezzo-sopranos), Caroline Trevor (alto), Kirsty Whately (harp), Claire Williams (organ), Alison Kinder (bass viol)

Missa de Beata Virgine – Kyrie, Gloria; Vespers of St Lucy; Anon (attr. Jean Mouton) – Ave mater matris Dei; Antoine Brumel – Mater patris et filia; Anon (attr. Leonora d’Este) – Virgo Maria speciosissima; Maistre Jhan – Ecce anima mea; Anon (attr. Jean Anchieta) – Mater Christi cooperto capite; Anon (attr. Leonore d’Este) – Vespere autem sabbati; Filrst Vespers of St Clare; Lauds and Second Vespers of St Clare; Joanna Marsh – The Veiled Sisters.

Digital only: Marguerite de Navarre – Avès poinct veu la malheureuse; Martha Baerts – Aen mijn Suster

LCKY 001 [76:00]

ABOVE: Musica Secreta (c) Robert Piwko