In recent years the San Francisco Symphony has indulged itself with a staged event in June. This year, with a tightened budget, it was a brief evening made of Schönberg’s Erwartung together with Ravel’s Mother Goose Suite.

Composed in 1909 Erwartung (Expectation) is musical Modernism’s most complex and emotionally wrought work. The Schöneberg masterpiece was placed alongside what may be Modernism’s most simple piece, Ravel’s Ma mère l’Oye (1911) — a piano duet of no technical and little musical challenge for the children of a friend. The next year Ravel expanded it into a small ballet suite for orchestra.

It was a strange pairing indeed, envisioned either by San Francisco Music Director Esa-Pekka Salonen or maybe by famed stage director Peter Sellars who created the minimal mise en scene for Erwartung.

The resulting performances were equally strange.

Ma mère l’Oye was entrusted to the Alonzo King Lines Ballet, San Francisco’s contemporary dance ensemble, with choreography by Alonzo King, the founder of the eponymous dance company. 12 dancers executed an unrelentingly complex, convulsive modern dance choreography that alternated full company moments with smaller ensembles of various numbers of dancers (see lead photo). The dances (a Spinning Wheel, Sleeping Beauty, Beauty of the Beast, Tom Thumb, Empress of the Pagodas, the Enchanted Garden) were very effective expositions of the impressive musculature of both the male and female dancers.

Meanwhile a reduced San Francisco Symphony was sequestered upstage on risers, creating the delicate beauty and sublime simplicity of the Ravel score, competing with the massive energy emanating from the dance platform.

On the other hand Peter Sellars reduced Schönberg’s overwrought, meandering Freudian monodrama for soprano into quite basic, very understandable terms. In Sellar’s version a woman’s lover has been the victim of a sudden death “while in custody’ (projected on the large supertitle screen, that other times offered additional gratuitous political overtones as well). In the brief, silent introduction the body is consigned to her who then embarks on her process to reconcile herself to his death.

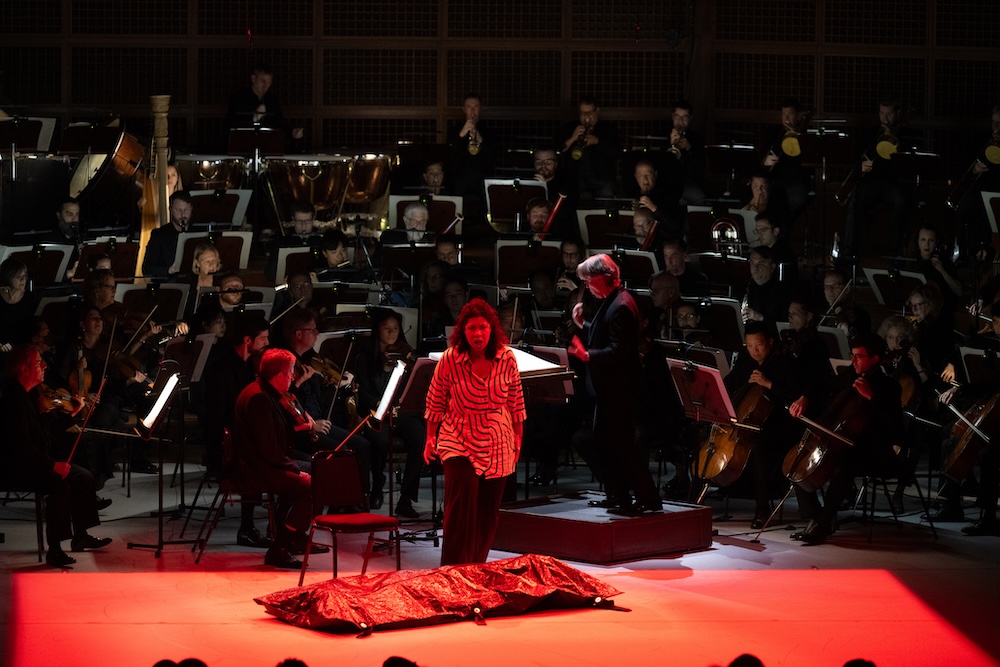

Now Schöneberg’s massive orchestra (quadruple winds, expanded percussion, full symphonic strings) spilled out onto the dance floor, leaving only a small, protruding square on which sat the soprano, Mary Elizabeth Williams, on one of the orchestra’s chairs. A body bag lay at her feet. She exposed her terrified grief in simple words, traversing her search for his love, the consummation of their love, the issue of their love, her fear that his world had betrayed him, that he had betrayed her, and that now she will be alone in the dawning light.

Dressed very simply in a white dress with vertebrae like black stripes Mme. Williams very directly exposed the immediate meaning of death. She possesses a dramatic soprano voice without the coloristic edges that soften the force of such a voice. She projects an honesty of emotion that is unique, specifically focused here in Schöneberg’s masterpiece on the terrifying reality of death.

From time to time a square of intense color would illuminate within the square of the small platform. Then at one point the confines of grief were burst open by a small rectangle of white light that suddenly extended up along the cellos of the orchestra where she moved, adding yet another perspective to the death of her lover — a brilliant Sellars coup de théâtre.

Meanwhile conductor Esa-Pekka Salonen focused the magnificent forces of the San Francisco Symphony onto realizing the astounding anti-repetitive thematic flows of Schöneberg’s fully atonal orchestration. A mass of sound was created that found a wonderful cacophonic harmony in this vivid contemplation of death.

Michael Milenski

Louise M. Davies Symphony Hall, San Francisco, California. June 8, 2024. All photos copyright Kristen Loken, courtesy of San Francisco Symphony.