The pit however is small for big opera, thus the baignoires (boxes) sitting just over the sides of the pit have long since been taken over by percussion. In the recent renovation of the OpÈra the pit was not enlarged making it necessary to requisition additional nearby baignoires to accommodate Poulenc’s generous post Romantic orchestration — the harps cotÈ cour (left side) and a piano cotÈ jardin. The OpÈra de Toulon was set up for a big evening.

New productions are rarely created in Toulon — this Dialogues of the Carmelites was an exception. Jean-Philippe Clarac and Olivier Deloeuil, the artistic team of some pretension that has overseen the OpÈra FranÁais de New York since 2005 were its authors. In recent years messieurs Clarac and Deloeuil have undertaken as well the stagings of large, non-operatic choral/orchestral works in important French theaters.

The techniques they have developed informed this staging of Poulenc’s Dialogues, the set more of an art installation than an integration of opera’s dramatic components. The ancien rÈgime (or ancestral home in this abstract staging) was a Louis XIV settee in a display case, the monastery was a white, hard-edge Stonehenge configuration. Interludes were visually inhabited by huge black and white projections of nuns’ faces enclosed in Revolutionary period habits when not enlivened by the a vista intrusion of stagehands (maybe the angry mob) to modify the elements of the installation — some benches became crosses and others became general mayhem (aka Place de la RÈvolution).

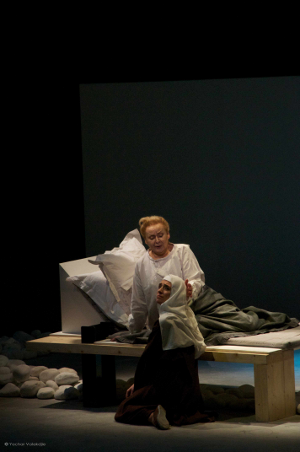

Nadine Denize as the Prioress and Ermonela Jaho as Blanche [Photo © Yachar Valekdjie courtesy of OpÈra de Toulon]

Nadine Denize as the Prioress and Ermonela Jaho as Blanche [Photo © Yachar Valekdjie courtesy of OpÈra de Toulon]

The coup de thÈ‚tre was, of course, the executions. A large white plaque descended with MORT written in straight neon lines, fifteen, uhm, make that sixteen little lines were extinguished one by one in concert with Poulenc’s hyper kitsch, not to say wonderfully effective, always moving finale. It even survived, almost, this staging. Believe it or not.

The mise en scËne did offer the singers ample space and relief to portray Poulenc’s very human characters struggling to reconcile life with death, fear with principle (and the list of conflicts goes on), the humanity in Poulenc’s startling opera exponentially intensified by installing it within spiritually competitive women. The impact of Poulenc’s opera is realized by the individual performances of five nuns, each performance contributing to the complexity and therefore effectiveness of the other performances. These are complicated women.

Toulon made it part of the way with Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho as Blanche, possessed by primal fears and questionable spirituality. No stranger to the Toulon stage (Mireille [2007], Thais [2010]) Mlle. Jaho is a large scale artist with a very fine instrument (thus a very big career). Blanche dominated the stage as Poulenc meant her to do, the stage having been set for her by the old Prioress Mme. de Croissy enacted by mezzo soprano Nadine Denize. The Prioress is dying, thus this cameo role is always undertaken by a magnetic singer, often retired who can gasp and hopefully emit a few good tones from time to time. Mme. Denize was appropriately magnetic, shall we say mesmerizing, and gasped with the best of them. Equally affecting was the role of Constance, the young nun whose impetuousness belied her purity, sung by French soprano Virginie Pochon.

The roles of MËre Marie de l’Incarnation and Madame Lidoine are dramatically more pointed. In fact the biggest singing of the evening is given to MËre Marie, once assumed to be the successor to the old Prioress, and who finally is the only one of the nuns who declines martyrdom making her the spiritual villain of Poulenc’s opera. The new prioress, Madame Lidoine is a simple, unassuming soul, who finally achieves emotional stature as an effective mother to her flock. Taken respectively by mezzo soprano Sophie Fournier and Spanish soprano Angeles Blancas Gulin these two roles did not contribute sufficient force of personality or voice to effectively complete the dramatic spectrum. The same may be said of the aumÙnier (chaplain) to the nuns sung by tenor Olivier Dumait.

Overseeing all this musically was octogenarian conductor Serge Baudo. The realization of Poulenc’s score lacked the urgency these spiritual dilemmas should provoke, and the musical energy required to keep this theater piece alive for two hours. Nor could the maestro impose sufficient control over the orchestra to assure clean entrances and cutoffs.

Michael Milenski

Cast and Production

Blanche de la Force: Ermonela Jaho; Madame de Croissy: Nadine Denize; Madame Lidoine: Angeles Blancas Guin; Le Chavalier de la Force: Stanislas de Barbeyrac; L’AurmÙnier: Olivier Dumait; Le Marquis de la Force: Laurent Alvaro; Constance de Saint-Denis: Virginie Pochon; MËre Marie de l’Incarnation: Sophie Fournier; Le premier commissaire: Thomas Morris; Le second commissaire: Philippe Ermelier; Docteur Javelinot: Jean-FranÁois Verdoux; Thierry: Thierry Hanier; MËre Jeanne: Sylvia Gigliotti; Soeur Mathilde: Rosemonde Bruno La Rotonda. Chorus and Orchestra of the OpÈra de Toulon. Conductor: Serge Baudo; Mise en scËne & scene design: Jean-Philiippe Clarac & Olivier Deloeuil; Costumes: Thibaut Welchlin; Lighting: Rick Martin. OpÈra de Toulon. January 29, 2013.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/IMG_2757%20%282%29.png

image_description=Ermonela Jaho as Blanche and Virginie Pochon as Constance [Photo ©FrÈdÈric StÈphan courtesy of OpÈra de Toulon]

product=yes

product_title=Dialogues of the Carmelites in Toulon

product_by=

product_id=Above: Ermonela Jaho as Blanche and Virginie Pochon as Constance [Photo ©FrÈdÈric StÈphan courtesy of OpÈra de Toulon]