Handel’s tangled tale of an episode during the First Crusade at the end of

the 11th century, drawn from Torquato Tasso’s epic Gerusalemme Liberata, is transferred to a 20th-century

boarding-school. Rinaldo’s heroic exploits – as he seeks to rescue his

beloved Almirena, with the help of fellow Christian knights, her father

Goffredo and brother Eustazio, from the dastardly clutches of Argante King

of Jerusalem and the sorceress Armida, and eject the Saracens from the Holy

City – become the wish-fulfilment dream of a frustrated adolescent, bullied

by his peers and beaten by his schoolmasters.

Perhaps it’s the historic and stylistic ‘distance’ of Handel’s operas from

our own time that encourages directors to overlay (overload?) them with

fanciful dramatic conceits, elaborations and excesses. Some might view such

meddling as disrespectful – to composer and audiences alike – but perhaps

such ‘translations’ are in keeping with the spirit of the

original? If we accuse such directors of ‘look-at-me-cleverness’, then

isn’t that just what Handel was ‘guilty’ of when he and showman-impresario

Aaron Hill presented the first performance of Rinaldo, at the

Queen’s Theatre Haymarket on 24th February 1711, dazzling the

audience not just with the vocal virtuosities of Handel’s ‘newly imported’

all-Italian company of star soloists, but also with excesses of lavishness

in the form of fire-snorting dragons, flocks of sparrows, mermaids and

aerial machines?

Contemporary literary critics held their collective noses, suspicious of

this new Italian art form which curmudgeonly ‘roast-beefers’ termed ‘an

exotic and irrational entertainment’. In The Spectator, Joseph

Addison and Richard Steele took every opportunity to satirise Italian

opera: ‘Spectatum admissi risum teneatis?’ (‘If you were admitted

to see this, could you hold back your laughter?’) was the Horatian epigraph

chosen by Addison for an account of Rinaldo which stressed the

dangers to theatre-goers posed by the illuminations and fireworks: ‘there

are several engines filled with water … in case any accident should

happen.’ Steele derided the real-life sparrows which took flight during

Almirena’s ‘bird-song aria’: ‘there have been so many flights of them let

loose in this opera that it is feared the house will never get rid of them;

and that in other Plays they may make their Entrance in very wrong and

improper scenes … besides the Inconveniences which the Heads of the

Audience may sometimes suffer from them’. When the stage-crew forgot to

move the wing-flats, the critics’ could not contain their glee: ‘We were

presented with the prospect of the ocean in the midst of a delightful grove

and I was not a little astonished to see a well-dressed young fellow in

full-bottomed wig, appear in the midst of the sea, and without visible

concern taking snuff.’

But, the opera was a sensation, Handel’s first London triumph: Rinaldo received 15 performances and was revived a number of times

in the years to 1731. Addison et al seemed to have been most

concerned with the liberties that opera takes with ‘reality’. In contrast,

Carsen relishes such liberties. And, if in 2011 there was some scepticism

about Carsen’s school-boy adventurism – Boy’s Own Magazine meets Harry Potter – then with each revival attitudes have softened,

warmed, and now the production looks to become a much-loved repertory

stalwart at Glyndebourne. Certainly, the capacity audience at the Marlowe

Theatre in Canterbury loved it.

Jake Arditti (Rinaldo). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Jake Arditti (Rinaldo). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Gideon Davey’s single set serves as white-washed classroom, schoolyard,

trainee dominatrices’ dormitory, and battle-cum-sports field. Smart in

regulation blazer and tie, Rinaldo enters the empty schoolroom at 8.55am,

pulls a portrait of his beloved from his satchel and pastes it inside the

lid of his school-desk. A globe sits imperiously upon the Headmaster’s

desk, a reminder of the Crusaders’ colonial imperialism, perhaps. The

blackboard is blank: a tabula rasa for the unhappy teenager’s imagination.

Just before the bell, a rowdy bunch of his peers burst in and, scenting a

weakness, see an opportunity for some sadism and bullying. And, why not?

They are, after all, only aping the Master and Mistress who then treat

Rinaldo to a caning.

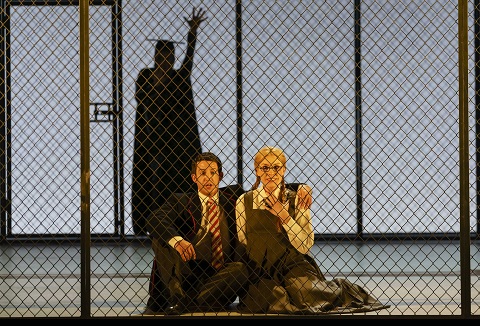

Jake Arditti (Rinaldo) and Anna Devin (Almirena). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Jake Arditti (Rinaldo) and Anna Devin (Almirena). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

However, as writers from Lewis Carroll to Philip Pullman have long known, a

child’s imagination sets them free. So, it’s off through the

blackboard-glass we go. Rinaldo and his classmates don silver breastplates

over their blazers; the Headmaster is transformed into a scheming Saracen,

while the Mistress morphs into a school-boy’s fantasy: a slinky sorceress

in dominatrix leather. Fired by Goffredo’s promise that victory in battle

will earn him Almirena’s hand in marriage, Rinaldo tracks down his beloved

amid the bicycle racks, only for Armida and her brigade of black-arts

bandits – who’ve traded their burqas for gothic fishnets and miniskirts –

to snatch her from his arms.

The ‘Crusaders’ set off to rescue her on flying bicycles – ET meets Mary

Poppins – stylishly choreographed to intimate the equestrian exploits of

their historical predecessors. There is visual spectacle and satire in

equal measure. A siren-chorus of identikit Almirenas tricks Rinaldo into a

boat and he finds himself imprisoned in Armida’s dormitory. Just when it

seems that Alminera faces certain death, the Christian Magician’s word

proves true – despite the mad scientist’s earlier explosive

experimentations in the chemistry lab – and Goffredo and Eustazio ‘storm’

Armida’s palace. Well, some heroic knights leapfrog the ramparts with

impressive athleticism, while others engage in a Morecombe & Wise

routine: a Fosbury flop pratfall prompts some self-preserving pragmatism

as the scenery is lifted, allowing the straggling Crusader to crawl his way

through.

Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

The final showdown takes place on the school playing-field, where, after

all, all significant battles are won: lacrosse and hockey sticks clash as a

large ball (the schoolmaster’s globe) floats balletically on the end of a

stick, imbuing the fight with cartoonish grace. Naturally, the Christian

Crusaders are triumphant. Rinaldo finds himself back in the empty school,

the clock-hand not yet telling nine o’clock …

The light-hearted lunacy of the proceedings was beguiling and undoubtedly

made more enchanting by the soloists’ mastery of the musical idiom. Jake

Arditti is no stranger to outrÈ Handelian outings, having sung the title

role in Longborough’s 2014 production which saw him cast as the strong-man

in the megalomaniac ring-master Argante’s circus. Here, he displayed

infinite stamina, streaming through the vocal fountains with pinpoint

precision, a fair amount of vocal embellishment, and envincing martial

confidence and heroic conviction. ‘Cara Sposa’, which Handel himself

considered one of his finest arias, was beautifully phrased and if it did

not seem quite languid enough to really touch one’s heart, then perhaps

Carsen’s prevailing comic irony made such sincerity hard to accomplish.

William Towers (A Christian Magician) and James Hall (Goffredo). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

William Towers (A Christian Magician) and James Hall (Goffredo). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Arditti’s fellow countertenors matched him for style, though James Hall’s

Goffredo needed a little more weight and stature, especially at the end of

Act 1 when he learns of his daughter’s kidnapping by the forces of

darkness. Tom Scott-Cowell’s Eustazio offered a lyrical complement to both.

Anna Devin sang Almirena’s ‘Augelletti, che cantate’ with purity and poise,

beautifully accompanied by the trilling birdsong of Rebecca Austen-Brown’s

sopranino recorder. ‘Lascia ch’io pianga’, in which the imprisoned Almirena

laments her fate, was also beautifully shaped, but I’d have liked a little

more hint of the intensity and spirit with which the maiden urges her

heroic rescuer on to victory.

Jacquelyn Stucker (Armida). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Jacquelyn Stucker (Armida). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

The task of delivering the feisty fury was left to Jacquelyn Stucker who,

as a fire-and-brimstone Armida, topped the vocal honours and commanded the

dramatic stage. Resplendent in shiny black latex – as fearsome as

Maleficent, that ‘mistress-of-all-evil’ in Disney’s Sleeping Beauty – Stucker sang with a sparkle like the luxurious

shine of rubies as Armida stamped and scorched her way through any obstacle

that dared to confront her. Like the scythe she wielded with relish,

Stucker’s soprano evinced a glamorous intensity with a real glint of

danger. It had both bite at the top and succulence in the middle, as well

as darkness at the bottom: it’s hard to imagine a soprano with the power

and range more suited to embody the evil enchantress’s schizophrenic

mood-swings – first she wants to destroy Rinaldo, then she wants to debauch

him, seduced by his heroism and nobility. Armida’s hissy-fit when her plans

are thwarted, and Argante proves unfaithful, was a sight to behold:

bed-linen and furniture went flying asunder, and she whipped through

Handel’s torturous runs, savouring the virtuosity. No wonder her acolytes

cowered and cringed before her. Aubrey Allicock’s Argante also seemed a

little overshadowed at times, though Allicock made a strong contribution to

Carsen’s irony.

The superb cast were supported by buoyant playing from the reduced-sized

Glyndebourne Tour Ochestra, conducted by David Bates. The recitatives had

vivid energy, supported by David Miller’s creative archlute, which

complemented the stage action; the fast numbers bubbled effervescently

while the more reflective numbers had time to make their mark.

I confess that my natural inclination is to flinch from the sort of

dramatic dabbling in which Carsen indulges here; but on this occasion I

found myself increasingly relishing an insouciant irreverence – and sheer

sense of fun – that Handel himself would surely have enjoyed. Such

cheekiness also has the merit of taking the spotlight off the Christian

triumphalism of the close: “O clemency of Heaven!”, “Blessed Fate!”,

“Virtue has triumphed!” cry the elated, conquering Crusaders. “O happy we!”

is the choric conclusion.

“After such cruel events, I don’t know if I am dreaming or awake,” says

Almirena, when she is rescued by her warrior-hero. And, at the conclusion of Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland Alice berates her sister Kitty for waking her,

reflecting on “who it was that dreamed it all. This is a serious question …

You see, Kitty, it must have been either me or the Red King. He was part of

my dream, of course—but then I was part of his dream, too!”

Carroll concludes:

In a Wonderland they lie,

Dreaming as the days go by,

Dreaming as the summers die:

Ever drifting down the stream —

Lingering in the golden gleam —

Life, what is it but a dream?

Sentiments with which, one imagines, Carsen would concur.

Claire Seymour

Goffredo – James Hall, Rinaldo – Jake Arditti, Almirena – Anna Devin,

Eustazio – Tom Scott-Cowell, Herald – David Shaw, Argante – Aubrey

Allicock, Armida – Jacquelyn Stucker, Woman – Catriona Hewitson, Siren 1 –

Chloe Morgan, Siren 2 – Rachel Taylor, A Christian Magician – William

Towers, Dancers (Caitlin Fretwell Walsh, Keiko Hewitt-Teale, Caroline

Lofthouse, Sarah O’Connell, Sarah Ward), Actors (Andrew Hayler, Nathaneal

James, Anthony Kurt Gabel, Bailey Pepper, Colm Seery); Director – Robert

Carsen, Conductor – David Bates, Revival Director – Francesca Gilpin,

Designer, Gideon Davey – Movement Director – Philippe Giraudeau, Revival

Movement Director – Colm Seery, Lighting Designers – Robert Carsen/Peter

van Praet, Glyndebourne Tour Orchestra.

The Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury; Friday 8th November 2019.

image= http://www.operatoday.com/GTO%20Rinaldo%20title.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Handel: Rinaldo – Glyndebourne Touring Opera at The Marlowe Theatre, Canterbury

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=Above: Jacquelyn Stucker (Armida) and dancers

Photo credit: Bill Cooper