Six years before he composed the Six Romances on Verses by British Poets (namely, Shakespeare, Raleigh and Burns), Shostakovich’s career as a composer of opera came to an abrupt halt following Stalin’s condemnation of his second and last opera, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District. The infamous, anonymous attack on Lady Macbeth, ‘Chaos instead of music’, which was published in Pravda, and the subsequent pressure put on Shostakovich by the Soviet authorities to withdraw his Fourth Symphony must have left him fearing that a trip to Siberia might be on the cards. So, one imagines that when, in 1942, with the Germany army advancing into Russia and Shostakovich himself exiled in Kuibyshev (now Samara), he set about choosing the six poems that would form his Op.42 Romances, the words – which address themes of loss, death and oppression – meant much.

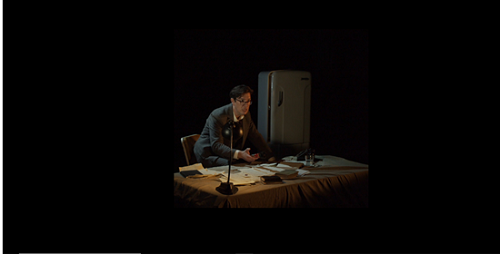

Shostakovich’s Six Romances open the final instalment of English Touring Opera’s digital series. James Conway’s staging of the cycle presents a lone figure – his suit crumpled, hair tousled, black round spectacles perched on the bridge of his nose – seated at a darkened desk, a lamp throwing frail light on messy piles of paper and books. Behind, two photographic portraits, one of Stalin and the other a woman – the composers’ first wife, Nina Varzar, perhaps – stare unblinkingly, as the man himself glares with wide-eyed anxiety at the black telephone.

It’s not a menacing ring that breaks the silence, however, but the sparse piano opening of the first Romance, ‘To his son’, a setting of Boris Pasternak’s translation of Walter Raleigh’s ‘The Wood, The Weed, The Wag’. Shostakovich addressed this song to Levon Atovm’ian, the composer, musician and administrator for the USSR Composers Union who had been disgraced and exiled in Turkmenistan. Raleigh’s warning is that the coincidence of the three seemingly harmless and unconnected elements of the title can be dangerous: “The wood is that which makes the gallow tree;/ The weed is that which strings the hangman’s bag;/ The wag, my pretty knave, betokeneth thee.”

Sergey Rybin’s rocking fifths have an understated pathos, simple and innocent but also vulnerable. As bass Edward Hawkins bows his head and began to write with urgency, in the hinterland shadows, a figure hovers – a haunting presence, signalling absence. Hawkins’ declamatory vocal line (the songs are sung in the original English/Scottish) have a bare, dark intensity, which deepens as the piano chords acquire weight and solidity. As Raleigh’s cautionary words become stabbing alarms, the vocal line rises: when the elements meet, “It frets the halter, and it chokes the child”. The toy soldier that Hawkins grips clatters onto the desk and the simple fifths echo once more as the music dissolves.

Placing the poem that he has written within the folds of a book, Hawkins notices a green ribbon marking a page. It triggers a memory, of love and loss. ‘O wert thou in the cauld blast’ is the first of three poems by Robert Burns which Shostakovich sets, in Russian translations by his friend, Samuil Marshak. Written on his deathbed, addressed to the young Jessie Lewars who helped him care for his children and tended Burns himself in his dying months, when he was aged just 37, this was the last poem that Burns wrote. Shostakovich dedicated the song to his wife, Nina. The melody seems to take inevitable shape, born from the lyricism of the poetry, the piano lilting gently, the voice unfolding tenderly from a quiet crooning. Hawkins’ convincing Ayrshire drawl infuses the song with human warmth. As he clutches the green ribbon, eyes closed, the female ‘ghost’ again flickers into being.

He opens the fridge and gazes confusedly into its bare depths. Flinging back the door, and revealing the gruesome teeth of a round sawblade, he launches into ‘Macpherson’s Farewell’ (which Shostakovich dedicated to his theatre director friend Isaac Glikman), relishing the bitter accusations and angry ripostes that the famous early 18th-century Scottish rebel flings at the woman who betrayed him and his executioner. MacPherson was a fine fiddler and at the scaffold he played a tune he had composed the night before, offering to give his violin to anyone who would play the tune at his wake. No-one stepped forward to take the fiddle, so MacPherson smashed it over the executioner’s head as the hangman’s rope fell. Hawkins spits, sneers and snarls, his facial expressions diabolical, deranged. He plunges blackly with the rueful rant, “It burns my heart I must depart,/ And not avenged be”, and dances a ghastly, jerky jig, spurred on by the piano’s jauntiness.

The dedicatee of ‘Jenny’, a setting of Burns’ ‘Coming thro’ the rye’, was the composer Yuri Sviridov. It’s a mischievous song and Rybin’s accompaniment prances with wry insouciance. Hawkins observes the eponymous maiden – drenched by the rain, dragging her petticoats through the rye fields – with a greedy eye and a lascivious smile, though the grin quickly fades to grimace as he seats himself for the next song, a setting of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 66 – a pained lamentation for the corruption and dishonesty of the world from which the poet wishes to be freed. (Shostakovich dedicated his setting of Pasternak’s translation to his friend Ivan Sollertinsky.)

Reaching under the desk for a valise, into which he stuffs his books and papers, Hawkins conveys the utter weariness which the piano’s stagnant bass pedal and unchanging harmony embody: “Tired with all these, for restful death I cry”. The grief for “maiden virtue rudely strumpeted” prompts the appearance of the female figure once more, more tangible now, wearing a red dress; a harmonic semitone shift brings not relief from the torpor but a forceful regret for “art made tongue-tied by authority”, the rage blackened by the piano’s oscillating semitone in the lowest realms. The final couplet sends the piano plummeting into dark dissonance once again: “Tired with all these, from these would I be gone,/ Save that to die, I leave my love alone.”

Packing the photograph of the woman into his case, Hawkins makes to depart, but his eye is caught by Stalin’s relentless glower. Dropping the latter’s photograph dismissively onto the now empty desk, Hawkins stares sarcastically at the ironic ‘gap’ on the wall and, clutching the toy soldier, delivers a gloating rending of the children’s nursery rhyme, ‘The King’s Campaign’: “The king of France went up the hill,/ With twenty thousand men;/ The king of France came down the hill,/ And ne’er went up again.” The exaggerated extension of line-closing words, the jumpy nervousness of the piano’s military tattoos, and the clash of naivety and cynicism make this song much more than a flippant after-thought.

As Hawkins moves aside, soprano Jenny Stafford emerges from the shadows, to perform Benjamin Britten’s song-cycle, The Poet’s Echo. Conway’s pairing is a pertinent one. Britten visited the Soviet Union six times between 1963 and 1971, and was respected there as a composer and performer. He formed close friendships with several Russian musicians, including Shostakovich and his second wife Irina, Sviatoslav Richter, and Mstislav Rostropovich and his wife, the soprano Galina Vishnevskaya for whom The Poet’s Echo was composed. Written while Britten was staying in the House of Composers in Dilizhan, Armenia, The Poet’s Echo was premiered by Vishnevskaya and Rostropovich (playing piano) in the Maly Zal (small hall) of the Moscow Conservatory on 2nd December 1965.

Conway’s direction is more understated in Britten’s cycle. When she enters, Stafford picks up the desk-lamp and tries to pierce the darkness. With Hawkins seated rear-stage-right, now himself in shadow, and Stafford occasionally gazing deeply into the folds of the misty mirror-screen in the centre of the Hackney Empire stage, it is as if Britten’s songs are themselves a light, momentarily illuminating memory. The songs seem, paradoxically, both immediate and ethereal, experienced strongly but issuing from ‘elsewhere’, and this otherness is enhanced by the gentility of Rybin’s delicate piano accompaniments, above which the vocal line soars and floats. Moreover, Stafford sings in the original Russian and while I can’t judge the authenticity of her diction, I do feel that her articulation softens the vividness or ‘edge’ of the language in a way which enhances the haunting quality of the settings. Thus, in the opening ‘Echo’ no sound or voice responds to the poet’s words. A warm assurance characterises the opening of ‘My heart, I fancied it was over’, which is propelled gently forward by the piano’s steady, repetitive step. Stafford’s soprano is gratifyingly full and even, and gleams when the poet-speaker remembers “That ancient rapture and its yearning … The dreams, the credulous desire”, before sinking low in more troubled reflections. When the “old wounds [start] burning/ Inflamed by beauty and her fire” Rybin injects a pained breathlessness that the voice is unable to resist.

Piano and voice are a wonderfully fused dramatic force in ‘Angel’, which ripples with restlessness and unease, the piano’s recurring rising motif counterpoised with strange stillness as the angel faces and defeats Satan with its humility and goodness. The fragile lamplight now extinguished, ‘The Nightingale and the Rose’ is compellingly enigmatic, the piano’s eloquence and insistence prompting an expansive outpouring of sorrow at the image of the disdainful rose that “dozes, nodding and swaying”, acknowledging not the nightingale’s “amorous hymn”, and then a retreat into impotent fragmentation and dissolution with the realisation that the poet, too, does not entrance his beloved with his art: “She is not listening, no poems can entrance her;/ You gaze; she only flowers; you call her; there’s no answer.”

The technical challenges of ‘Epigram’ are considerable, and Stafford is more than equal to them. During the final song, ‘Lines written during a sleepless night’, she lowers herself to the floor, the photographic portraits placed before her. Rybin’s circling torments and teases, as ceaseless as the midnight minutes that tick by, as “life slips by …” “What’s your purpose, tedious whispers?” the poet asks, “What is this you want to tell me?” There is no answer.

This filmed performance is available to watch, free of charge, until 29th January.

Claire Seymour

Shostakovich: Six Romances on Verses by British Poets

Edward Hawkins (bass), Sergey Rybin (piano), James Conway (director), Tim van Someren (film director)

Britten: The Poet’s Echo

Jenny Stafford (soprano), Sergey Rybin (piano), James Conway (director), Tim van Someren (film director)

English Touring Opera, filmed at the Hackney Empire; Friday 1st January 2021 (streamed on Marquee TV).

ABOVE: Jenny Stafford in The Poet’s Echo