After an eighteen-month absence, at least at the Coliseum, English National Opera is back on home turf and marking its return to live performance with a reboot of Philip Glass’s Satyagraha. It’s the second of his three portrait operas (there’s also Einstein on the Beach and Akhnaten) and examines Mahatma Gandhi’s rise from struggling lawyer in South Africa to international spiritual leader. Now in its fourth revival, Satyagraha (meaning ‘truth force’) may still confound expectations or generate apoplexy amongst commentators who consider the work an anti-opera, but its message of non-violent protest in the light of recent events is as relevant today as it was when the work first appeared in 1980 in Rotterdam. As ENO’s new artistic director, Annilese Miskimmon, announced before the show began, ‘This opera is about how ordinary people coming together can change the world’.

For a work in Sanskrit using Constance de Jong’s untranslated libretto drawn from the ancient Bhagavad Gita, and without a conventional and chronological narrative (or even the absence of anything that might resemble an aria, or a plot with character development), Glass is unconcerned with any sense of operatic tradition. Yet Robert Maycock, in his book Glass A Portrait (2002), suggests the composer is ‘credited with rescuing the art form from stagnation’. Certainly, Satyagraha is one of Glass’s most successful of his forty-odd stage works, and is still one of the ENO’s most profitable productions.

A handful of critics still hark on about the music’s monotony. Yet Satyagraha’s obsessively repetitive musical patterns (not unlike the perpetual motion of Bridget Riley’s artwork) and their restless instability perfectly counterbalance the long-breathed melodic lines given to the singers. The music’s circling motions neatly reflects a narrative that circles around its subject. That Glass seems to harness the tensions between turmoil and unruffled poise is surely one of the work’s strengths.

Phelim McDermott’s staging, a collaborative venture with the theatre company Improbable, continuously dazzles the eye. Sight and sound are utterly compelling, but while visual clues abound in this staging the audience are required to join up the dots of disconnected events related to Gandhi’s non-violent protests between 1893 and 1914. As a series of tableaux, Satyagraha is very much a show, not tell, opera.

Looming over each of the three acts (and providing their titles) is the silent presence of Leo Tolstoy, Rabindranath Tagore, Martin Luther King, three figures, perched in an alcove above the stage, who inspired or drew inspiration from Gandhi’s evangelising. Then there is designer Julian Crouch’s extraordinary vision of Gandhi’s years in South Africa, where events are largely projected through allusion. Reams of newspapers (ingeniously point to the radical publication Indian Opinion), giant papier-mâché puppets suggest Gods and yards of cellotape serve to symbolise the march of striking miners in Newcastle (former British colony of Natal) in defiance of the 1913 Immigrants Regulation Act. Much of the stage action is magically shaped by a cast of stilt walkers and puppeteers. But the singers also play their part, literally so in their shoe removal scene, symbolising Gandhi’s decision to wear only a loincloth, and the ritual burning of identity cards signifying the protest at the South African government’s decision not to revoke its anti-Indian discrimination.

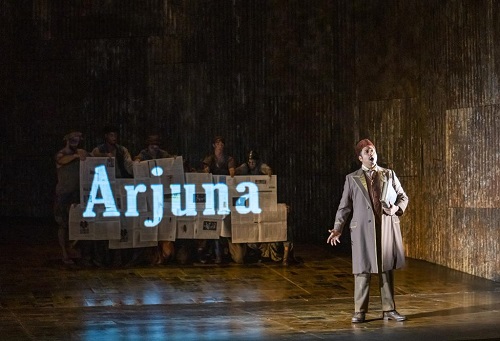

The singing is beyond praise not least for the cast’s fierce commitment to a memory-defying score with its endless repetitions for both the chorus (sung with absolute certainty and masterly in the Act Two laughing scene) and soloists. Chief amongst these is the Asian-American tenor Sean Panikkar – critically acclaimed for his central role with Los Angeles Opera in 2018 – whose dignified presence commands attention, as does the ease with which he soars over the orchestral fabric. Mrs Alexander is powerfully sung by Sarah Pring and there is stalwart support from Gabriela Cassidy as Miss Schlesen and well-defined contributions from Musa Ngqungwana (Lord Krishna), James Cleverton (Mr Kallenbach) and Ross Ramgobin (Prince Arjuna). In the pit, Korean conductor Carolyn Kuan produces miracles of precision, drawing meticulous, detailed playing that registers every shift in colour and metre. Whether you call this opera or music theatre, ENO has fashioned a wonderful production, its success related not just to the sum of its parts, but the tireless dedication of its staff and cast clearly revitalised with its return to performances.

David Truslove

Philip Glass: Satyagraha

M. K. Gandhi – Sean Panikkar, Lord Krishna – Musa Ngqungwana, Miss Schlesen – Gabriella Cassidy, Mrs Alexander – Sarah Pring, Parsi Rustomji – William Thomas, Mrs Naidoo – Verity Wingate, Kasturbai – Felicity Buckland, Mr Kallenbach – James Cleverton, Prince Arjuna – Ross Ramgobin, Skills Ensemble; Director – Phelim McDermott, Conductor – Carolyn Kuan, Associate Director & Set Designer – Julian Crouch, Revival Director – Peter Relton, Costumes – Kevin Pollard, Lighting – Paule Constable, Video Designer – Leo Warner & Mark Grimmer, English National Opera Chorus & Orchestra.

Coliseum, London; Thursday 14th October 2021.

ABOVE: ENO Chorus and Sean Panikkar © Tristram Kenton