A third staging of French stage director Benjamin Lazar’s poetic and sophisticated production (Malmö in 2017 and Karlsruhe in 2019), highly refined in Montpellier by an early music tenor as Pelléas and an actress who sings as Mélisande.

Each of these two singers brought specific vocal tonalities that created lost mystical beings who wander Maeterlinck’s darkly forested world, much like the three starving (mute) beggars and his silent serving women, thus separating the protagonists from the men who inhabit a decaying castle. These men are richly voiced, but men who are blind — Mélisande’s husband Golaud who cannot see truth, and his great grandfather Arkel who is blind but sees, finally, hopelessness.

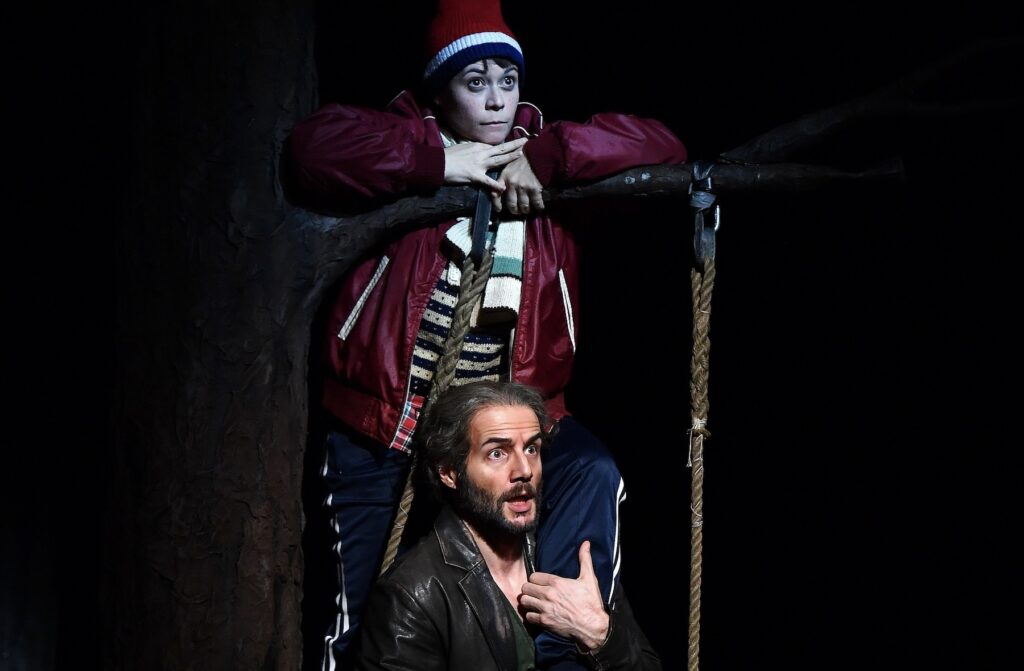

Director Benjamin Lazar creates a further world, that of Golaud’s son Yniold, rich in innocence and intuition, and this world is present from the first orchestral interlude as Yniold dashes about like a sprite. It is into this innocent world that Pelléas and Mélisande slide. In the opera’s emblematic moment, Mélisdande’s tresses falling from the tower, Mélisande stands on Yniold’s swing as a delighted Pelléas wears the crown Mélisande lost when Golaud came upon her, picked up in the woods by Yniold.

The scene is famously dismissed by Golaud as child’s play. Child’s play as well was Yniold’s wrenching intuition that his toy sheep have no home.

Director Lazar makes Pelléas et Mélisande far more than a tawdry love triangle. His stage is in fact not a home, it is a dark forest. As Debussy’s piles on Maeterlinck’s symbols in his orchestra, Lazar piles on images of light that penetrate into this forest, the first are the headlights of Golaud’s ATV and his flashlight discovering the lost Mélisande. The castle appears only in vague outlines. Therein hang sometimes three electrically lighted chandeliers. At the moment of disaster five carefully placed spotlights blasted vivid light directly into our eyes. We too were blind.

The scenes of the opera are changed in the dark, with careful light revealing a small bridges, a pier, Arkel’s chair, Yniold’s tree, the castle, a fallen tree — the tree that later is where Golaud slays Pelléas, and finally it becomes a headboard against which Mélisande dies, arms extended not as a crucifix image but in abject vulnerability.

As the symbols pile on from the libretto, from Debussy’s orchestra and from Lazar’s staging, we lost track of the love triangle as we were overwhelmed by the individual philosophic plights of Pelléas and Mélisande, of Golaud, of Arkel and of Yniold.

Thank the stage machinery of the Opera Comique at the opera’s 1902 premiere (it couldn’t handle the quick scene changes the opera requires) for the interludes that Debussy created to make time for changes. In the Lazar staging the scene transitions were in the dark, sometimes peopled, the later ones were in black, shattering orchestral statements of despair.

It was a spellbinding evening. From the first timid sounds of Debussy’s dark world from the Orchestre Nationale de Montpellier we felt the presence of this musical world vibrating in the wooden floor of the venerable old (1888) Opéra Comédie. Ukrainian conductor Kirill Karabits (music director of the Bournemouth and Weimar orchestras) later brought this fine French orchestra to shattering volumes in Act IV as Arkel imagined a new, lighted world, a world quickly destroyed by the angered Golaud. The maestro held Debussy’s musical spell through the almost silent ending of the opera. The theater was totally enthralled.

Pelléas was sung by baritenor Marc Mauillon whose usual repertoire is Baroque opera and Offenbach. As a Pelléas he was of lighter voice and presence than the Pelléas we have come to expect. Mr. Mauillon however totally owned the role in this production, his Pelléas was a vulnerable creature lost in a complex web of conflicting loyalties. He was vocally convincing both in his delighted play with Mélisande and in the ultimate, highly emotional distress and confusion of his love for Mélisande.

Mélisande was sung by actress Judith Chemla, known to director Lazar through his 2016 production of Traviata, vous méritez un avenue meilleur at Paris’ Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord. Mme. Chemla is not an opera singer, rather she is a chanteuse with an amazing capability to accomplish this Mélisande, a Mélisande fraught with a vocal vulnerability that supported her emotional and philosophic vulnerability. This quite unusual, indeed quite wonderful Mélisande was a Mélisande for the theater, not a recording studio.

Golaud was sung by American bass baritone Allan Boxer, whose finishing preparation was at the Dresden Opera. Though at the initial stages of a promising career he created a fully formed, powerful Golaud who evinced our enormous sympathy by a handsome presence and his quite beautiful voice. He was gentle in his initial encounter with Mélisande, brutal in his denouncement of her, and at the end quite moving in his desperate pleas for truth.

Arkel was sung by veteran French bass Vincent Le Texier who, though seeming to embody a personage of extreme age, sang with a warmth of tone that anchored the philosophical underpinnings of the production. He was Maeterlinck and Debussy’s continuum, motivated by hope, and finally resigned to despair. With conductor Karabits he rose to powerful persuasion in his lust for a better world placing his kiss on the forehead of Mélisande.

Yniold, a huge presence in this production, was sung by French soprano Julie Mathevet, a carryover from the original Malmö cast. Within the scope of this production her vocal confidence was necessary (she sings Queen of the Night elsewhere), as were her histrionic gifts, rendering director Lazar’s Yniold as an additional protagonist in this philosophical treatise. The opera’s final image was Yniold holding, rocking Mélisande’s child.

Geneviève was sung by Élodie Méchain and the Doctor was sung by Laurent Sérou.

Production information:

Orchestre et Choeur Opéra national Montpellier Occitanie. Conductor: Kirill Karabits; Stage director: Benjamin Lazar; Scenery: Adeline Caron; Costumes: Alain Blanchot; Lighting: Mael Iger. Opéra Comédie, Montpellier, March 13, 2022.

All photos copyright Marc Ginot, courtesy of the Opéra national Montpellier Occitanie.