The crowning jewel of Mozart’s operas has arrived at the War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco Opera now completing, finally, the Covid thwarted rollout of an integrated Mozart/DaPonte trilogy.

The trilogy has been staged by Canadian director Michael Cavanagh, mining American cultural histories first in the Jeffersonian world of black slaves and its pursuit of liberty, then in the genteel world of Southern comfort in the smug complacency of a repurposed Colonial mansion, now a country club. But in Don Giovanni, director Cavanagh creates American history by imagining the state of Virginia in the year 2080, a sort of deconstructed Monticello (a neoclassical abstraction thereof) as a post apocalyptic ruin, its façade draped in tattered strips of stars and stripes.

French conductor Bertrand de Billy obliged Mr. Cavanagh with a great big, sweeping, sometimes violent reading of Mozart’s overture that well supported the Armageddon action projected on the show scrim — though amidst the flames and smoke we really couldn’t know what was the good and what was the evil. A lot of things did come to mind, none seemed relevant.

What and who was left was Leporello’s shopping cart and a hand turned generator that could illuminate a small lamp (as well as project the mille tre names of Don Giovanni’s Spanish conquests onto the Monticello façade). And, besides the fashionably, late twenty-first-century-attired aristocrats, a rag tag group of Mozart’s peasants, some obviously homeless, others dressed like the festive vagabonds of San Francisco’s Haight Street (a remnant of its last century Flower Child culture).

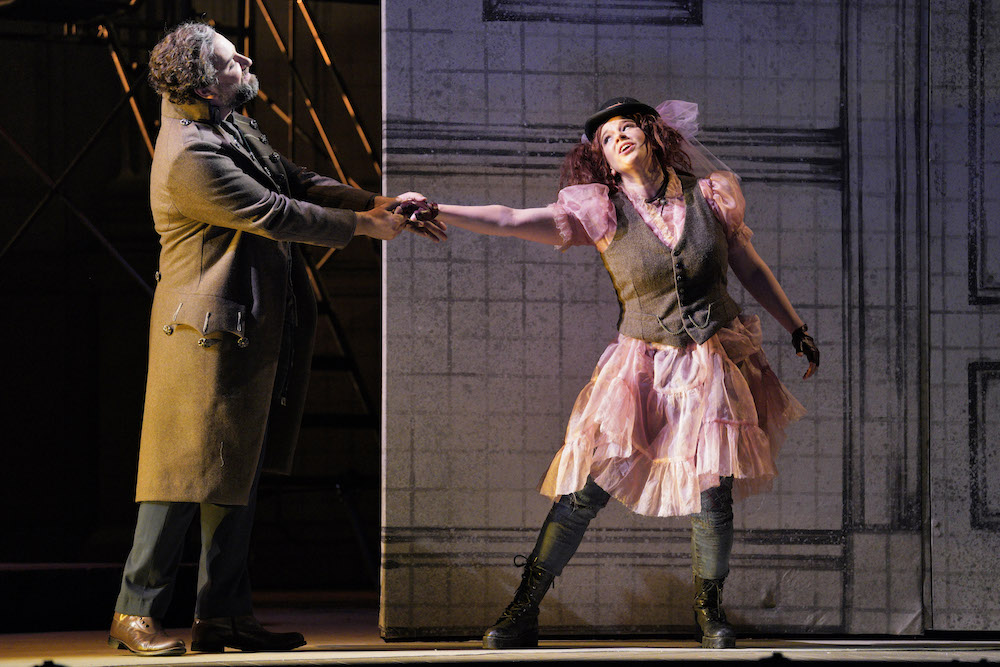

Present most of all was libido, pure and simple — the irrepressible libido of Don Giovanni, though there seemed no general shortage. [Lead photo is Don Giovanni with Donna Anna, soprano Adela Zaharia.]

The stage bathed in an apocalyptic yellow light, Don Giovanni slaughtered the Commendatore, bantered with Leporello, avoided the love-crazy Elvira as best he could, assuaged the orphaned Donna Anna as best he could, seduced Zerlina, — masterfully to say the least, manipulated Leporello ruthlessly, and grandly and heroically met his fate amidst the flames (quite real) of hell.

Though set in the rubble of annum 2080 it was an absolutely straight forward reading of the DaPonte libretto. Relaxed, easy and deeply thorough.

The action flowed seamlessly, maestro de Billy finding a sweep of sound that filled the 3000 seat opera house, encouraging a beauty of tone that complemented the beauty of voices on the stage (and they were indeed beautiful). The great second act prima donna arias, Donna Elvira’s “Mi tradi quell’alma ingrada” and Donna Anna’s “Non mi dir,” were notable for a graceful lyric flow that rendered them absolutely magical works of art — art that only unfettered libido could possibly engender.

The entire Michael Cavanagh’s trilogy was above all witty and charming. In the Don Giovanni however these myriad moments of wit and charm were but the cornerstones of Mozart’s classically structured arias and finales, forms that took on new, unexpected monumentality against this destroyed vision of America’s cultural neoclassicism.

A master of moving his actors around the stage, in Don Giovanni Cavanagh made much use of the stage’s fourth wall (the proscenium opening), Leporello sighting the Commendatore’s tomb first out there in our midst as example. But he used the fourth wall most of all when Mozart’s actors literally “hit the wall” — nothing to do but sing about what had happened. Thus they simply lined up across the front of the stage, faced the [transparent] wall and held forth in our faces.

This was the formation for Mozart’s encomium to the opera’s denouement. Giovanni dispatched into hell, his survivors line up across the stage in front of the scrim on which the apocalypse had been projected. Monticello, dimly behind, is somewhat reconstructed. But they in fact have nothing much to say other than memorialize the just desserts of he who does evil on earth — “quest è il fin di chi fa mal.” But what evil can it be (toxic masculinity?) that inspires such magnificent music?

In addition to this imposing house debut of conductor Bertrand de Billy, there were four cast debuts, Australian soprano Nicole Car as Donna Elvira, German soprano Adela Zaharia as Donna Anna, Canadian bass baritone Etienne Dupuis as Don Giovanni and American baritone Cody Quattlebaum as Masetto, formidable artists currently performing these and other roles in the great theaters of the western world.

These high octane performances were indeed equaled by Austrian bass baritone Luca Pisaroni (once a SFO Figaro) as an easy going, new age Leporello. Zerlina, was presented as a big, new forceful and very charming presence by Austrian mezzo Christina Gnash (once at SFO for Handel’s Orlando). The able presence of Adler alumnus Amitai Pati made the fine, hapless Don Ottavio. Excellent bass Soloman Howard sang Donna Anna’s father, the Commendatore.

Aspirational casting.

Michael Milenski

Production information:

Stage Director: Michael Cavanagh; Set and Projection Designer: Erhard Rom; Costume Designer: Constance Hoffman; Lighting Designer: Jane Cox. The San Francisco Opera Chorus and Orchestra. Conductor: Bertrand de Billy. War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, June 10, 2022.