A John Adams premiere is about the biggest news event the opera world can generate. Here’s the news from San Francisco.

Antony and Cleopatra is the first opera John Adams has created without the input of stage director Peter Sellars. The libretto is now the work of composer Adams himself who, like Richard Wagner, has thus assured its compatibility to his very own, particular animus. Like the seventy-four year old Giuseppe Verdi for his Otello, seventy-five year old Adams renders a Shakespeare play into opera. And like Falstaff (and Pelleas et Melisandre), Adams’ Anthony and Cleopatra is text driven — a play set to music.

It is the text of Antony and Cleopatra largely comprised of old Shakespearean language and rhythms (though some Dryden Virgil as well) that is the John Adams muse, his music from its first sounds capturing the richness of verse, the atmospheres of poetry and the urgencies of drama. Far from the minimalist sobriquet associated with Adams the score exploded in infinite details that beguiled us for a more than three hour duration. The conducting of San Francisco Opera music director Eun Sun Kim surcharged the Adams score to art song on steroids.

The Adams opera tells the Plutarch tale in bold strokes. The powerful warrior Anthony, smitten by the wily, seductive Cleopatra, rebels against the wily, ambitious Octavian, but loses a huge naval battle when he follows the unexplained retreat of Cleopatra’s ships. Forced to beg Octavian’s (soon to become Caesar Augustus, the first Roman emperor) mercy, Anthony and Cleopatra are torn apart in their responses to Caesar’s (Octavian) deceits. To regain Anthony’s love Cleopatra feigns death, Anthony, who seems none too swift, believes it, so he tries to kill himself. They come together, Anthony dies, Cleopatra summons the asp.

If only it were that simple. Shakespeare weaves his story with 40 named roles in 42 scenes. Adams pulls it down to twelve roles in nine scenes, though the scenes are quite complex indeed — Adams wishing to incorporate as many of the Shakespearean complexities as he possibly can. Thus we have nine more personalities who both enact and embellish the story in many, many added words (tough for us to process), though offering composer Adams myriad opportunities to create very magnificent music.

The Antony and Cleopatra music is awesome in and of itself, dwarfing the personalities and actions of his protagonists and their acolytes.

Adams worked with stage director Elkhanah Pulitzer [yes, of the famed St. Louis Pulitzer family], and her dramaturg Lucia Scheckner to imagine and realize the opera. They consider it a study of power, of nations and individuals. It is, according to Adams, quite modern because of its focus on the seizure of power (Octavian), the empowerment of women (Cleopatra), and the vanity of masculine strength (Anthony). Adams believes it therefore to be a worthy successor to his famed earlier collaborations with Peter Sellars — Nixon in China, Klinghoffer and Dr. Atomic.

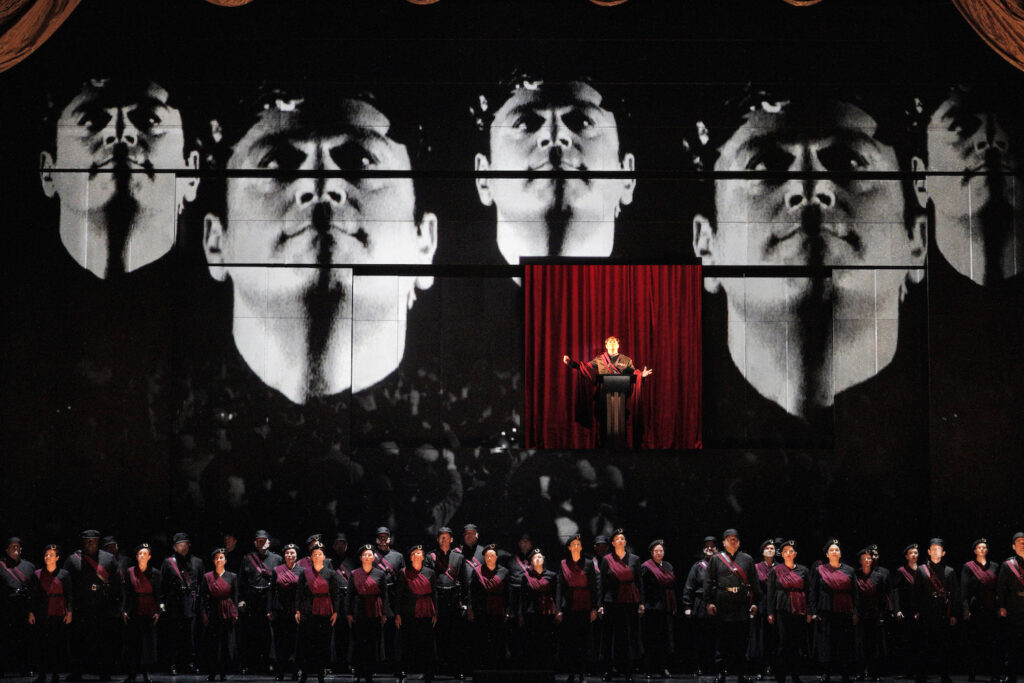

The setting is both an abstracted ancient Egypt and a (the) Hollywood golden era that idolized the doomed couple. Much effective use of video projection was made, the work of designer Bill Morrison. Specifically there were two 1930 black and white newsreels from Italy — the marriage of Mussolini’s daughter, and the marriage of Umberto II, the last king of Italy. The staging is highly abstracted, the great naval battle has choristers holding poles topped by a tiny, square sail shape, Octavian’s huge Trump/Hitler-like rally has the red sashed chorus in a line across the front of the stage, Octavian’s face in caught in huge, repeating, black and white video images.

The stage set by Broadway and theatre designer Mimi Lien (a former MacArthur Fellow) is spectacular. A black, huge full stage camera lens covers the stage, magically opening and closing, revealing ever new, techni-colorful staging pictures on the floor and at random elevations. Designer Lien traversed the opera’s three continents with great ease and restraint, the actors themselves declaiming location on a mostly barren stage, supported by the costumes, spectacular as well, by Constance Hoffman, — white or light for Anthony and company, dark or colored for Caesar and company, simmering metallic colors for Cleopatra and company.

San Francisco Opera assembled a prestigious support staff for the production, a joint venture with the Metropolitan and Barcelona operas, that included lighting designer David Finn. And there was a surprising credit for an “intimacy director!”

Always noteworthy is composer Adams’ addition of voice amplification. The sound design and mixing was undertaken Mark Grey, a technician of great experience. Conductor Kim’s orchestra was very present — too present, quite loud, skewing a possible, plausible relationship between pit and stage, the voices finding a too low relief.

Anthony was sung by baritone Gerald Finley, a veteran of Dr. Atomic in San Francisco and at the Met, a voice and presence well known to Mr. Adams, that well suited the middle aged, besot, not too bright warrior created by Adams and Shakespeare — though Mr. Finley is often cast as Scarpia on the world’s major stages.

The Cleopatra role was created for soprano Julia Bullock, who withdrew. San Francisco Opera had its own, real Egyptian princess in the wings, soprano Amina Edris (lead photo) who made the role her own in shimmering, golden tone. The melodic flow is determined by intervallic colors rather than a succession of tones, exploring the full reaches of the soprano range. It is a big, long role, obviously quite difficult to master. It was well executed indeed by Mlle. Edris.

Tenor Paul Appleby was the Caesar Augustus/Octavian, this estimable artist well acquainted with the repertory’s more interesting roles (Tom Rakewell, Pelleas, etc.). He found the sound and presence for a rising, young, ambitious tyrant, his big rally diatribe was terrifyingly familiar (magnified by its spectacular staging), and all too believable.

Noteworthy were the roles of Caesar’s lieutenant Agrippa, sung by baritone Harleigh Adams (no relation) and Anthony’s aide Eros, sung by tenor Brenton Ryan, both artists finding the complex, internal rhythms of composer Adams’ texts, and making their lines incisive and musically real. Agrippa suffered his beating by Anthony’s thugs with great aplomb. Eros’ suicide was one of the few felt moments of the performance I attended, text and music coming together in sublime, momentary solemnity.

Performance dates in New York and Barcelona have not been announced. It will be interesting to see what changes may be effected. This San Francisco premiere is but the initial exposition of a potential masterpiece.

Michael Milenski

Cast and Production Staff

Cleopatra: Amina Edris; Anthony: Gerald Finley; Chairman: Taylor Raven; Eros: Brenton Ryan; Enobarbus: Alfred Walker; Caesar/Octovian: Paul Appleby; Agrippa: Hadleigh Adams; Lepidus: Philip Skinner; Octavia: Elizabeth DeShong; Scarus: Timothy Murray; Iras: Gabrielle Beteag; Maccenas: Patrick Blackwell. San Francisco Opera Orchestra and Chorus. Conductor: Eun Sun Kim; Stage Director: Elkhannah Pulitzer; Set Design: Mimi Lien; Costume Designer: Constance Hoffman; Lighting Design: David Finn; Projection Designer: Bill Morrison; Sound Design: Mark Grey. War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, September 23, 2022.

Above image: Amina Edris as Cleopatra. All photos copyright Cory Weaver, courtesy of San Francisco Opera