“On this happy and auspicious day which marks the end of the amorous sufferings of our demi-god, let us sing, shepherds, such sweet melodies, that worthy of Orpheus may be our concerts.” So implores the Shepherd at the start of Act 1 of Monteverdi’s Orfeo, in an earnest appeal to celebrate the forthcoming nuptials of Orfeo and Eurydice – to which the nymphs and shepherds respond with a carefree canzonet in praise of Hymen, whose “flaming torch” brings to the lovers “cloudless days”.

Watching the opening of director Silvia Costa’s new production of Orfeo in Hannover one would never guess that joy and love infuse the pastoral dances which charm more than “the stars which dance in heaven”. Instead, and drawing on the patterning imagery of Striggio’s text, the ominous foreshadowing of the doubting Orfeo’s tragic backwards glance – as his vision of Euridice’s sweetest eyes succumbs to a shroud of darkness – dominates the overture and the opening scenes.

During the military flourishes of the Toccata – which at the first performance in the Gonzaga palace in Mantua, in 1607, would have accompanied the entrance of the Duke and his entourage – a hanging gauze curtain presents the audience with a projected image (video, Furio Ganz) of the face of Orfeo (Luvuyo Mbundu): the two eyes fracture into kaleidoscopic patterns, mingling then merging, a mosaic of refracting glances, anticipating tears and embodying suffering.

When the curtain rises we are in a world upon which the shadows of Hades weigh heavily, banishing pastoral brightness and colour, imposing a charcoal coldness. Even the song of La Musica (Nikki Treurniet – who also takes the role of Euridice) cannot lift the gloom. The Prologue is not a direct address to the audience, simultaneously asserting and beguiling them with the power of Music and drawing them into the drama to follow. Rather, La Musica’s verses are sung behind a curtain by a veiled figure. A puppet owl atop a small lyre – both propped up by a single stick, positioned centre-stage – serves as our conduit into Ovid’s mythical narrative.

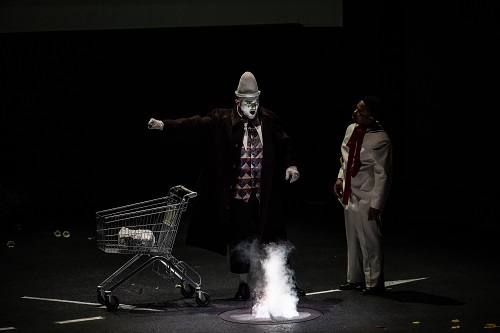

Costa’s designs seem intended to deny any possibility of joy and hope. Two grey, constructivist cubes stand in the centre of the stage, some palely blossoming foliage the only concession to the pastoral. When Charon is charmed to sleep by Orfeo’s mesmerising ‘Possente spirto’, one cube will recede inside the other and a silky grey shroud will be drawn over the hefty block, as we descend, through metal grids, to an anthracite Underworld. There’s scarcely any difference between the sunny world of mortal pleasures and Pluto’s dark domain. Costa ignores the distinct change in instrumental timbre that marks the shift to the Underworld, though the muted colours of the overcoats and umbrellas sported by the ‘nymphs and shepherds’ are replaced by body-painted women and statuesque Spirits in flapping black shorts who emerge and recede through the mists, more monstrous than magical.

So much seems to be presented as ‘ritual’ rather than lived experience. So, the dances of the opening acts are choreographed not as an expression of nuptial joy, but as a series of repeating physical gestures, creating an oddly static effect, as if the musical ritornelli that structure the work embody a time-loop. A team of Red Cross nurses, perched atop one of the cubes, tend to the stricken Eurydice, before dangling down a red sash (the serpent’s tongue?) which Orfeo ties around his own neck. When Orfeo learns of Euridice’s demise at the fangs of a snake, the response from the shepherds is a gesture of grief which suggested blindness, as they place their palms across their eyes, and their hands on each other’s shoulders, meandering in a mournful progress. Indeed, there is a ‘motionless’ quality about this production which is entirely at odds with the spirit of the dance that infuses Monteverdi’s score.

And, there are some strange ‘motifs’: this Euridice seems to be pregnant (and a pram is pushed across the stage at one point); in Act 5, when Orfeo vents his despair at having forever lost his Eurydice, he takes an ice sculpture in his arms, then dashes it to the floor, decapitating the cold figure. Perhaps he does not really want his love to return to him? Indeed, Costa’s emphasis on misery and stasis makes it difficult to discern any ‘love’ between Orfeo and Euridice.

The role of Orfeo is customarily taken by a tenor, or high baritone. Luvuyo Mbundu is neither. His darker baritonal timbre perfectly matches Costa’s conception but does little to bring the expressive litheness and richness of Orfeo’s ‘parlar cantando’ to life. He sang confidently but this Orfeo’s lyre conjured no magic. After the first act, Orfeo appeared to have gilded teeth, which only served to confirm that all that glitters is not gold.

Nikki Treurniet did what she could with the Prologue, singing with clarity and shapely phrasing, but this Euridice is condemned to darkness and has little opportunity to convey the qualities that have so enamoured Orfeo. Markus Suihkonen was an eloquent Charon; Richard Walshe evinced Pluto’s power and magnificence. Philipp Kapeller, Pawel Brozek and Woo-Jung Kim fulfilled their roles as Shepherds and Spirits with commitment. Countertenor Nils Wanderer displayed striking vocal character as the Messenger. Nina van Essen’s vibrant Prosperina cast much needed illumination into the Underworld.

I usually enjoy David Bates’ interpretations, in which scholarship and practice impressively cohere. On this occasion, though, I felt that he did not conjure the innate energy of Monteverdi’s score, nor its life-enhancing colours and timbres. Perhaps the darkness on stage weighed heavily on the Lower Saxony State Orchestra in the pit? The dances did not seem to me to spring and spin with a madrigalian spirit; and Bates encouraged some strange ‘surges’ in the strings which felt unidiomatic. Too frequently, the low organ seemed to dominate the texture. Some of the choral numbers were unaccompanied (chorus master, Lorenzo Da Rio) but they did not make the impact that they might have done.

Monteverdi’s original plan for the ending of Orfeo – the intervention of Apollo transporting Orfeo to the heavens – as evident in the published score of 1609, had to be eschewed two years earlier, owing to the restrictions of the small room in which the first performance was staged. In Costa’s production, there was never any likelihood of divine intervention bringing transfiguration. So, we were left with neither the dismemberment of Orfeo by the deranged Bacchantes nor an ascent to the heavens. Just a strange, grey, somewhat muted ambiguity.

Claire Seymour

Orfeo – Luvuyo Mbundu, La Musica/Euridice – Nikki Treurniet, Nymph – Petra Radulović, First Shephed/First Spirit – Philipp Kapeller, Second Shepherd/Second Spirit – Pawel Brozek, Third Shepherd/Messenger – Nils Wanderer, Another Shepherd – Woo-Jung Kim, Prosperina – Nina van Essen, Charon – Markus Suihkonen, Pluto – Richard Walshe, Apollo – Marco Lee, Dancers – Teodora Fornari, Chiara Viscido, Marianne Besser; Director and Designer – Silvia Costa, Conductor – David Bates, Costume designer – Laura Dondoli, Lighting designer – Bernd Purkrabek, Video designer – Furio Ganz, Chorus master – Lorenzo Da Rio, Dramaturg – Martin Mutschle, Chorus of Staatsoper Hannover, Lower Saxony State Orchestra.

Staatsoper Hannover, Germany; Friday 28th April 2023.

ABOVE: Luvuyo Mbundu (Orfeo) (c) Sandra Then