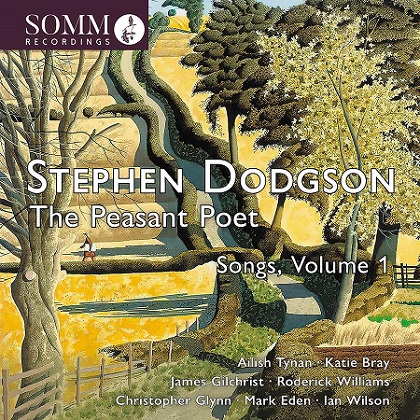

There were many things that drew me to The Peasant Poet, a disc of songs by Stephen Dodgson (1924-2013) – which was released by SOMM Recordings last year, marking the 10th anniversary of the composer’s death – not least the fact that I know embarrassingly little about his life and music, and that the songs are performed by a reassuringly accomplished team of ‘SOMM regulars’. But, one particular thing that caught my eye was the eclectic nature of the texts set by Dodgson – discussed by John Warrack in his booklet article which is complemented by Robert Matthew-Walker’s thoughtful comments on Dodgson’s life and career – which range from poems by John Clare, Ezra Pound and Walter de la Mare, to the work of lesser-known English poets, from the folk verse of his native London to Australian ‘bush ballads’.

This is the first disc in a planned three-volume series devoted to Dodgson’s songs, of which there are more than 100. His role as a BBC radio broadcaster from 1957 onwards made him a familiar voice on the airwaves, but as a composer it was his music for the guitar that was, and is, best known. His friendship with Julian Bream resulted in his First Concerto for the instrument, in 1956; at that time Dodgson was teaching at the Royal College of Music where one of his harmony student was John Williams, who also performed the work. A Second Guitar Concerto followed in 1972, and altogether he composed more than 40 works for the instrument.

In the 1990s, he was asked to compose a guitar duo for two students at the Royal Academy of Music, Mark Eden and Christopher Stell, who subsequently, as the professional Eden/Stell Duo, commissioned a Concertino for two guitars and strings, Les Dentelles. The Duo gave the work its London première at the Purcell Room in October 2001. It seems fitting, then, that the first cycle on the disc is Dodgson’s Four Poems of John Clare, in which the tenor James Gilchrist is accompanied by Eden. Three of the poems are concerned with depictions of birds and animals; the second of the set – which gives the disc its title – expresses Clare’s profound attachment to his rural locality, positioning within the scene, ‘A peasant in his daily cares,/ A poet in his joy’.

In ‘The Peasant Poet’, Gilchrist shapes the arioso line discerningly, negotiating its angularity and taxing peaks with precision and care. Eden complements the meditative mood at the start and end of the poem, conjuring nature’s soft sounds, but the duo effectively heighten the central episode, when the ‘dismal storm’ seems to the transfixed onlooker evidence of Nature’s divinity and power, ‘The very voice of God’.

Eden’s nimble accompaniment captures the ‘tittering, tottering’ sideways stumbles of the ‘Trotty Wagtail’, as well as the brightness of the words in this merry song, which Gilchrist enunciates with characteristic clarity. The humorous musical imagery – the waggle of the bird’s tail elicits a melodramatic melisma, while his chirruping gets stuck on repeat – has a lovely childish quality, though in the slower final stanza there’s a respect and sincerity in Gilchrist’s farewell address to ‘little Master Wagtail’.

Clare returned frequently to scenes depicting the human intrusion on animal life, and we have two such episodes here. In ‘Turkeys’, the waddling, gobbling birds defend their eggs from intruders, human and animal – ‘the old dog snaps and grins’ but does not ‘venture nigh’. Eden’s jangles have a confident, dismissive air, and Dodgson’s rhythmic asymmetries evoke the strutting of the indifferent birds who ‘sprunt’ their tails and ‘nauntle’ at passers-bye. The fox, too, evades his pursuers – the shepherd, ploughman, old dog, and the woodman, eventually finding refuge in a badger-hole: ‘He lived to chase hounds another day’. But, if there’s cunning and defiance at the close, the song has a darker quality, the varied repetitions of the guitar’s motifs creating a restlessness beneath Gilchrist’s persuasive storytelling. Human cruelty is recorded with a dispassionate eye – the ploughman beats the fox ‘till his ribs would crack’ – but the vocal line becomes imbued with intensity here, enhanced by the harmonic twists and turns.

Gilchrist also sings ‘Inversnade’, a setting of Gerald Manley Hopkins (‘Inversnaid’) in which the poet envisions the deleterious impact of human life on the scarred environment, juxtaposing ‘wilderness’ and ‘wildness’. I’m not convinced that Dodgson evokes the tenor of this poem; his song is rather ‘chirpy’, with a repeating curlicue motif in the piano accompaniment (which Christopher Glynn sculpts with lovely variation of emphasis and colour). With immaculate diction, Gilchrist conveys the imagery with clarity, though, making something of the rather unpropitious vocal melody. And, the harmony of the closing lines at times has a Finzi-esque quality, which, together with the unaccompanied vocal motifs, does imbue the imploration, ‘Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet’, a poignant urgency.

‘Slow, Slow Fresh Fount’ is sung by Echo upon the death of Narcissus, in Act 1 of Ben Jonson’s play, Cynthia’s Revels (1600). Dodgson sets Jonson’s madrigalian poem in the manner of an Elizabethan lute song, with pictorial word-painting – underpinned by some harmonic nuances which recall the expressive affect of Renaissance false relations. It’s beautifully sung by Gilchrist, capturing the grief of Echo as she mourns not just the loss of her beloved but also the languor and moral decay of Cynthia’s court, and its sensitively enhanced by Glynn’s transparent traceries.

The short poems of Ezra Pound’s 1926 collection, Personae, might not seem likely candidates for musical setting, with their irregularity of rhyme and metre and general impression of intellectualism and ‘artifice’. But, there are moments of lyric beauty as well as rhetorical weight, which Dodgson explores in the four songs which form Tideways. In ‘The Needle’, Gilchrist and Glynn convey the significance of the moment, as the speaker stands, figuratively, at the turning of the tide. The sparseness and low accompaniment create a momentous quality, while the vocal line has some Britten-esque nuances. ‘The Gypsy’ canters along, propelled by trotting unisons in the piano and vocal melismas, and if it’s not a setting that really does justice to Pound’s epiphanic representation of himself as a poet-gypsy, a Wanderer, or clarifies the dense allusiveness of a text which looks back to a mythic past and folk traditions, then Gilchrist and Glynn perform it with authority and commitment.

Soprano Ailish Tynan sings the first and last song of the Pound set. ‘Psyche’ has a gentle lilting quality. Tynan soars delicately but freely above Glynn’s rocking patterns, and momentarily heightens the closing image with discernment. Here, and in ‘Doria’, Tynan could do more with the words, though: tone quality, which is beautiful, is prioritised over consonants. Her diction is better when the soprano takes us from the cerebral artfulness of Pound to the folky grit of Joseph Campbell, ‘The Mountainy Singer’ from Belfast, who was also known as Seosamh Mac Cathmhaoil, a republican poet interned by the Irish Free State in 1922-23, and the author of Irishry.

The four poems set by Dodgson confirm Campbell’s pithy poetic economy and ability to create telling drama within small means – and, also, Dodgson’s inventive humour. We have ‘Tinkers’ whose souls are ‘free from walls’, a filthy rag-and-bone man who rattles round and round the street, and musings on life – ‘Boys grow to men and marry, and till their bit of ground:/ And women bear them children, and so the world goes round.’ – as a midwife rushes through the night to attend a woman in labour. Glynn’s accompaniments vividly evoke the contrasting characters, situations and moods: robust interpolations suggest the trials of a travelling life but also the tinkers’ inner strength; the teetering to-ing and fro-ing of the ragman is conjured by the trotting rhythm and circling vocal line. Tynan sings with unaffected line and clean tone in ‘The Mill Girl’, a poignant portrait of the effect of life’s trials on a once beautiful young girl who now passes by, ‘Hiding her travail/ In a shawl’. The extended final note of the song impresses upon the listener the affecting image conjured by Campbell.

In Dodgson’s setting of an ancient Irish poem, ‘The Monk and his Cat’ (which was also set by Samuel Barber in his Hermit Songs),Tynan paints an affectionate portrait of a monk who lives a solitary life alongside Pangur, his white mouse-hunting cat, each intent on their own pursuits: ‘Though we are thus at all times,/ Neither one of the two every hinders the other.’ Ian Wilson’s recorder unfurls some deliciously contented flutter-tongued ‘purrs’, and perhaps, too, a few squeaks from the mouse who feels the pointed precision of Pangur’s sharp claws, while Glynn’s jumpy chords evoke the flash of the cat’s eyes and the tension of the chase.

The nursery rhyme ‘Mrs Hen’ has a similarly ironic bent, and mezzo-soprano Katie Bray is a spirited teller of the story of childhood impatience – why is the hen so slow to lay three eggs for supper? – and disillusionment: punished and ‘eaten to the bone’, she’ll lay no eggs no more. Bray’s account, in ‘Five Eyes’, of the nocturnal hunting of the miller Hans’s three black cats with five bright, ‘smouldering’ green eyes between them is no less entertaining and crisply delivered. Glynn delights in the musical wit and word-painting, and delivers a resoundingly brisk scamper and pounce in the postlude.

The highlight of the disc is the series of six songs which comprise Dodgson’s Bush Ballads (Second Series), which are sung by baritone Rodney Williams. The composer explained that his three series of Bush Ballads, which were written over a period of nearly three decades, had been inspired by a ‘happy encounter’ with the Penguin Book of Australian Ballads. The texts conjure a host of characters in situations both humorous and grim, and Williams brings them to life with characteristically engaging artistry and warmth. We feel the wry grievance of the convict, transported to Botany Bay just for ‘meeting a cove in an alley/ And stealing his ticker away’, whose carefree refrain, ‘Singing too-ra-lie, too-ra-lie, addity’ – which trips lightly off Williams’s tongue – is juxtaposed by a touching outburst of yearning and love as he dreams of soaring ‘Slap bang to the arms of my Polly-love’. Williams softens and lightens his baritone, and sings with wonderfully natural phrasing, to embody the ‘Sick Stockrider’ who asks the old, loyal Ned to lift him down from his horse and lay him in the shade. The tender portrait ends with a poignant image of eternal repose which Williams sings with melting tenderness.

When ‘Holy Dan’ finds that his supplications are insufficient to stop the Lord taking his bullocks during a Queensland drought, his change from righteous calm to blasphemous fury is brilliantly enacted by Williams who fairly spits out Dan’s cursing diatribe. The latter unleashes the riotous laughter of his previously patronised fellow drivers which in turn triggers a thunderstorm, in which ‘Holy Dan was drowned’. The final word is a veritable growl of divine retribution! ‘The Style in Which It’s Done’ is an ironic glance at the ‘link’ between crime and punishment, to which Glynn’s accompaniment adds a grimly black tone. ‘Old Harry’ has a contemplative lyricism, and Williams makes the narrator’s memory of Old Harry Pearce pushing his bullocks on through the heat of noon, seemingly ‘walking on the air’, both strange and reassuring. There’s an almost Chaucerian drollness about ‘The Parson and the Prelate’ which takes a sharp look at the priesthood, power and pomposity.

‘Heaven-Haven’, a setting of Gerald Manley Hopkins, offers a very different portrait of religious vocation. The poet-speaker, a nun, has already embraced the afterlife, and her calm embrace of eternity is presented with refinement by Williams. Glynn also contributes two of Dodgson’s Eight Fanciful Pieces, ‘A Leaf in the River’, which shimmers with Debussy-like delicacy and gleam, and ‘Shrovetide Process’, in which the pianist balances stateliness and elegance.

This is an incredibly interesting and engaging disc. Dodgson may not be the strongest melodist, but his settings make one think about the texts and their concerns. He is done excellent service by all the performers. I look forward greatly to the next instalment of his songs.

Claire Seymour

Ailish Tynan (soprano), Katie Bray (mezzo-soprano), James Gilchrist (tenor), Roderick Williams (baritone), Ian Wilson (recorder), Mark Eden (guitar), Christopher Glynn (piano)

Stephen Dodgson, The Peasant Poet: Four Poems of John Clare, ‘Mrs Hen’, ‘Heaven-Haven’, ‘Five Eyes’, ‘The Monk and his Cat’, Bush Ballads (Second Series), ‘A Leaf in the River’ & ‘Shrovetide Procession’ (from Eight Fanciful Pieces), Irishy, Tideways, ‘Inversnade’, ‘Slow, Slow Fresh Fount’

SOMMCD 0659 [64:02]