Ruddigore has always had a problematic status in the G&S canon. Following hot on the heels of The Mikado, its premiere in 1887 was met with catcalls and jeers. Some rejigging saw the piece run for 288 performances – Gilbert quipped that he wouldn’t mind having a few more such ‘failures’ – but the opera wasn’t revived until D’Oyly Carte’s 1921-22 season (with further cuts to Act 2 and a new overture).

Ruddigore is unusual in that it lampoons not the British politics, institutions and class system that were the usual target of W.S. Gilbert’s satirical pen, but the Victorian theatre itself – specifically the melodramas that were the favoured fare in theatres on the south side of the Thames.

There is a curse upon the Murgatroyd family: the bearer of the baronetcy has to commit at least one crime a day or else die in agony. The latest heir to that title, Sir Ruthven, has ducked his destiny by faking his own death and living incognito as a humble farmer, Robin Oakapple. And, he’s fallen in love with the local beauty and do-gooder, Rose Maybud. His younger brother, Sir Despard, has thus been forced to assume his fated role, and it’s no wonder he’s delighted to be enlightened by Richard Dauntless, a returning sailor – supposedly ‘Robin’s’ buddy, but really his romantic rival – and vengefully interrupts Ruthven’s wedding to Rose. Thus, ends Act 1. Act 2 bring the All Souls’ Night release of the ghosts of the formerly cursed, physically afflicted, Murgatroyd barons. Needless to say, it all ends happily, tragedy flipped to comedy by some last-minute legal niceties.

Ruddigore thus ventures into self-parody. Gilbert, who had done something similar before, in his pre-Sullivan 1871 musical play A Sensation Novel, recognises the shallowness of those Victorian stereotypes – the virtuous heroine, the wicked villain, the Jolly Jack Tar, the giggly girl choruses – that are the staple of his own libretti, and he turns them on their head. So, the heroine of Ruddigore is both a prig, blinded by etiquette manuals, and romantically flighty; the patriotic sailor is a snake-in-the-grass; the goodies and baddies swap places; the supernatural revenants are as benign as those pirates of Penzance. Thus, Victorian moral absolutes are upended, shown to be worthless. Gilbert is not mocking the mocked – those plain, menopausal spinsters that frequently populate his libretti, for example – but those who do such mocking. And, his Topsy-Turvy world is topsy-turvyed, so to speak.

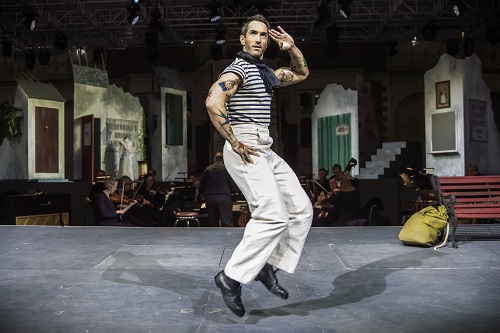

Will a twenty-first-century audience recognise such theatrical conventions and their parodic subversion? Does it matter if they don’t? At Opera Holland Park, John Savournin and Charles Court Opera pushed such questions aside. Savournin, here both directing and performing – as he did, brilliantly, in The Pirates of Penzance in 2021 and last year’s H.M.S. Pinafore – is a modern-day master of this repertoire. He must have been born with G&S in his blood. And, Gilbert’s inverted universe seems to be his natural demesne. The librettist was working both within and against Victorian theatrical genres, and Savournin knows how and when to play it straight and when to waggle the handle-bar moustache or flourish the scarlet cape.

He also knows how to make a theatrical space ‘work’. The wide stage which always presents challenges at Holland Park has been further problematised by taki’s brilliant solution to pandemic-related performance issues – the narrow fore-strip that encircles the orchestral pit, pushing the audience further from that expansive stage. This season, both Cecilia Stinton (Rigoletto) and Natascha Metherell (La bohème) have struggled to make the most of that front-strip, but Savournin brought the characters into the audience’s embrace, siting all the action within their grasp and using the main stage for sweeping entrances and exits, tightly choreographed ensembles, and panoramic vistas of the Edwardian village of Rederring – economically sketched by designer Madeleine Boyd with no-frills efficiency and oudles of charm.

The first-night performance of the run was choreographed to perfection by Merry Holden (chorus master, Richard Harker). Those candy-flossed bridesmaids and bowler-hatted gents didn’t waste a bar of Sullivan’s jauntiness or a single bounce of Gilbert’s beat. The animated corpses, supposedly emerging from a gallery of portraits but here flowing through the audience from the rear, were posed with polish – doorways, balconies and windows making perfect ‘frames’. The head of one headless ghost even had a cameo.

Gilbert supplies a fantastic array of insanely over-the-top characters, too. And, the Charles Court cast relished every ounce of the lunacy. If there were to be accusations of ‘over-acting’, then one would riposte that this was entirely fitting to the mock-melodrama. My only quibble might be that the spoken dialogue didn’t always come across clearly (and the text seems to be even more crucial than usual in Ruddigore) despite – or perhaps because of – the tendency to shout. A different venue might have prompted a different approach and outcome.

As ‘Robin’, Matthew Kellett’s lovely baritone made one yearn that his romantic endeavours would have a happy outcome, even while – through his singing-acting prowess – he captured the disguised baron’s gaucheness. Rose’s prissiness isn’t easy to make attractive, but Llio Evans made ‘If somebody there chanced to be’ amiable rather than irritating. Heather Lowe’s ‘Mad Margaret’ was brilliantly deranged – full-on Lucia di Lammermoor at times (I’m sure I heard a flute curlicue). What a masterstroke to have Meg and her regained betrothed, Sir Despard, appear in tweeds and horn-rims – as if this pair could ever conform to middle-class mediocracy! And, of course, Savournin nailed all the nails that needed hammering and hamming.

David Webb was a frisky Richard Dauntless, though his accent wasn’t entirely convincing, and Steven Gadd, as the recently deceased Sir Roderic, hurled out ‘When the night wind howls’ with theatrical aplomb – though at such moments one felt the lack of orchestral oomph (where were the hair-raising brass surges?). David Eaton conducted the pared-down City of London Sinfonia vigorously, and made the most of his small resources – stepping in to tinkle the ivories, melodrama-style, at times – but he couldn’t entirely overcome the economy of means.

Towards the close, Gadd’s Sir Roderic and Heather Shipp’s Dame Hannah (Rose’s aunt) share a lovely duet, ‘There grew a little flower’, unexpectedly reunited (and made more poignant by Gilbert, as the Dame would conventionally have been a cross-dressing role). This was a wonderful moment of tenderness. Forget the youngsters’ superficial romances; here was true love. If you weren’t moved by that, then you have no heart.

So, Savournin played it straight – droll not splashy – but didn’t read Gilbert straight. Perhaps one might have liked a more corrosive bite at times. But, Savournin’s G&S hovers on the cusp of turning into something else while being allowed to be just what it is – utterly brilliant!

Claire Seymour

Sir Ruthven Murgatroyd – Matthew Kellett, Sir Despard Murgatroyd – John Savournin, Sir Roderic Murgatroyd – Stephen Gadd, Richard Dauntless – David Webb, Old Adam Goodheart – Richard Suart, Rose Maybud – Llio Evans, Mad Margaret – Heather Lowe, Dame Hannah – Heather Shipp, Zorah – Natasha Agarwal, Ruth – Caroline Carragher; Director – John Savournin, Conductor – David Eaton, Designer – Madeleine Boyd, Lighting designer – Mark Jonathan, Choreographer – Merry Holden, City of London Sinfonia and the Opera Holland Park Chorus (Chorus Master – Richard Harker)

Opera Holland Park, London; Wednesday 9th August 2023.

ABOVE: Cast & Chorus of Opera Holland Park’s co-production of Ruddigore with Charles Court Opera © Craig Fuller