The late, justly mourned Pierre Audi, general director of the Aix Festival for these last seven festivals, matched renowned conductors and stage directors to create monumental stagings of the gamut of the repertory.

None have been more monumental than this staging of Mozart’s Don Giovanni.

Simon Rattle, once principal guest conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, more recently music director of the Berlin Philharmonic, now music director of the London Symphony was brought together with Robert Icke, famed in the London theater world for his adaptations of the classics, and known to New Yorkers for Hamlet, Uncle Vanya, Oresteia (et al) at Pierre Audi’s Park Avenue Armory. This Aix Don Giovanni marks Mr. Icke’s opera debut.

Add to these impressive credentials the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra — one of Europe’s most prestigious orchestras — and a cast of eight mighty singers to embody the production’s musical and dramatic conception. This ensemble of forces worked in perfect synergy.

Of huge complexity.

Much as Robert Icke’s Covid-era, Park Avenue Armory adaptation of Ibsen’s The Enemy of the People was a monologue meditation by a single actress, this Don Giovanni was a meditation on the force and weakness of the human condition by conductor Rattle and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra.

Simon Rattle offers some explanation to the production in an interview in the program booklet, “We live in an imperfect world, and this opera is a sort of mirror of this divine imperfection.” The musical conception was heroic, and brutal, of classical perfection, and of human frailty. It was of purely symphonic scope, Mozart’s usual symphonic resources of double winds (though three trombones for the infernal scenes), strings and percussion enacting an enormous, abstract panorama of human life.

Robert Icke plays with big philosophic ideas, hardly the dissolute nature of a single man. Mr. Icke’s Don Giovanni is a discussion of the overwhelming force of love, be it carnal or spiritual or simply convivial. It is this love that dominates and destroys mankind, but it is this same love that is the salvation of the human spirit. Don Giovanni, in the end, becomes a Christ-like figure who sacrifices himself to salvage the soul of man. Donna Elvira, a Mary Madeline figure, in the final image ascends to embrace the condemning, now dead Commendatore, the ultimate incarnation of Don Giovanni.

It is a hugely complicated dénouement. It was a wrenching experience, of gigantic philosophic proportion and expansive, explosive contemporary imagery.

Or something like the above.

Don Giovanni was played by Italian (South Tyrol), Salzburg-finished baritone Andrè Schuen. Mr. Schuen is of incisive voice with a brilliant golden sheen, capable of seemingly infinite modulation, notable in his second act serenade of Donna Elivira’s servant girl, here an 11 year-old girl with a coloring book. She appears from time to time throughout the opera. At first you suspect that she is a pederasty victim, though in the serenade you understand that she is but Cupid himself — though without the blindfold nor Cupid’s wounding arrow (you will have already seen some blood, you will see more). In his serenade Mr. Schuen’s Don Giovanni became the enraptured victim of this child.

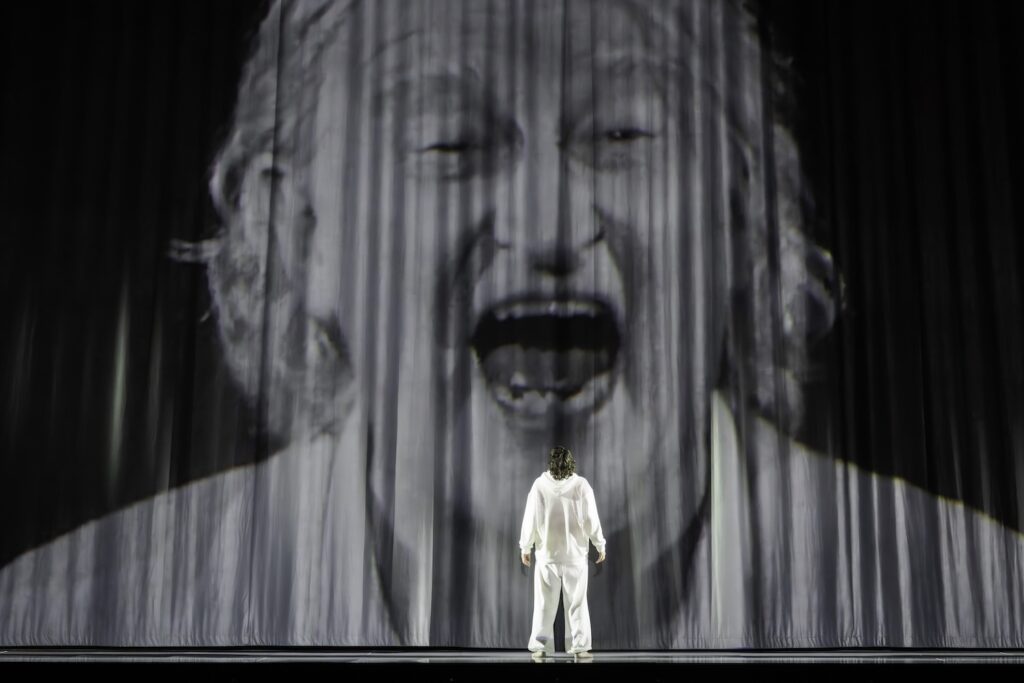

A very physical performer in loose fitting hospital patient whites, Mr. Schuen leapt upon the Zerlina seduction couch, tiptoed across its back, then brutally rolled down twenty or so steps into a ruined heap at the end of Act I (or was it a stuntman double?). He hobbled around the stage for much of Act II attached to stand with drip bag.

Donna Elvira was played by Czech soprano Magdalena Koźená, who was in fact blind-folded in the second act as she is fooled by the caresses of Leporello. With consummate musicianship she effected her “Mi tradi” in complex phrasing that challenged and renewed our understanding of the piece, bridging its meanings to the broader emotional premise that she, like Giovanni, suffers from love, but is not crippled by it. Her voice is of great tensile strength, and means solid emotional business in its combination of copper and zinc like colors. Mme. Kožená’a “Mi tradi” burned the stage.

Polish bass Krzysztof Baczyk (lead photo, with Don GiovannI) played Leporello. Dressed in dark pants and a white blazer for the duration, at first you think he may be the only adult in the room. Though in the second act he too succumbs, if only playfully to the easy caresses of Donna Elvira. He remained typically nonplussed, if terrified at the truly explosive battle taking place at Giovanni’s supper with the Commendatore.

Though Mozart’s title is Don Giovanni, Mr. Icke’s take on Mozart’s opera was really about the Commendatore — who is actually Don Giovanni! The Commendatore appeared during the overture — paused while he listened to a screechy old recording of Mozart’s battle music, then died in a video of intense hospital activity once the real orchestra again took over. Played by veteran British bass Clive Bayley (last season’s nude Mad King), the Commendatore personified life itself, culminating in the huge, mythical battle of Dionysos versus Apollo (Giovanni versus the Commendatore). Mr. Bayley was surely not miked during the battle — though maybe he was — given the apocalyptic volume inflicted by the maestro.

We the audience had been warned that there were amplified sound effects, and begged for our understanding — to the scratchy recording add the occasional eerie sounds of feelings, feelings felt by the protagonists that could not be suppressed (these occurred fairly frequently), plus amplified, throbbing heart beats, and a few loud booms, and maybe even some hidden acoustical help for the final battle. Given the extreme theatrical nature of the evening these sounds added to the Mozart score were easily accepted.

Zerlina was played by New Zealand, London-finished soprano Madison Nonoa who boasts a bright, young voice of considerable size. She was the first to be bloodied by Cupid’s invisible arrow — in her rush of hormones her arms became belted above her head onto the scenic structure. Masetto was played by Polish, Munich-finished bass Pawel Horodyski, a voice and persona of virile importance, who succumbed to his beatings, then to embrace the comforting Zerlina with delicate grace.

Donna Anna was played by South African, Juilliard-finished soprano Golda Schultz. Mlle. Schultz’s voice has an exciting play of overtones that render it both beautiful and innocent, bringing these attributes to roles like Liu, Micaela, the Countess, and now Donna Anna. She remains an innocent spirit in Mr. Icke’s Don Giovanni, while gaining some perspective into the plight of humanity, joined in her “Non mi dir” by the bevy of swimsuit beauties who first paraded onstage during Leporello’s Catalogue Aria. Her intended, the bespectacled Don Ottavio was played by New Zealand, San Francisco-finished tenor Amitai Pati, his two lovely, beautifully sung arias kept well in the background, his quiet domestic life with Donna Anna questionably assured.

It was splendid casting.

Robert Icke’s high-theater-art team included scenographer Hildegard Bechtler, costumer Annemarie Woods, videographer Tai Garden, lighting designer James Farncombe, sound designer Mathis Nitschke and dramaturg Klaus Bertisch.

Michael Milenski

Grand Théätre de Provence, Aix-en-Provence, France. July 6, 2025

All photos © Monika Rittershaus, courtesy of the Aix Festival