And how the work suits such an approach; in many respects, the

deconstruction has already been done. Probably Jan·?ek’s greatest

opera, indeed his greatest work of all, it is no accident that it is

the one Pierre Boulez chose to conduct, towards the end of his life.

Alas I never heard that live, although in 2014, I would see

Patrice ChÈreau’s production

in Berlin. That was, of course, a fine piece of theatre, as indeed was

Krzysztof Warlikowski’s Covent Garden staging

, seen earlier this year. Castorf, however, revelling in its

fragmentary nature – for it is in many respects his own – triumphantly,

I should say dialectically, offers the strongest sense of a whole I

have seen or could imagine. By taking it as it is, Castorf’s team and a

magnificent cast, aided greatly by Bavarian State Opera forces under

Simone Young in the finest performance I have heard from her, alert

both to the needs of the minute and of the greater architecture,

present and represent the opera as it is and might be. Quite without

sentimentality, they write and rewrite, igniting and reigniting that

Dostoevskian redemptive spark that is both present and absent

throughout, depending when and where one looks and listens, how and

with what one pieces together one’s own narrative, musical and

dramatic.

Photo credit: Wilfried Hˆsl.

Photo credit: Wilfried Hˆsl.

We are in Russia – no doubt of that. It is Russia at a dark time –

again no doubt of that. (When, however, was that not the case, save for

a few years under Lenin, and even then…?) But is it a ‘real’ Russia?

And what indeed could so impossibly naÔve a formulation mean? Live

camerawork performs all manner of tasks, questioning our ability to

comprehend, to view, to narrate, whilst making it all the more

necessary that we try to do so. There is little doubt concerning the

realism – until, that is, a true Carnival of the Dead comes amongst the

prisoners and the prison. Magic realism? Perhaps, but if so, it is the

blackest of magic to follow, perhaps even to sublate, the blackest of

comedy and (non-)redemption. Whereas, in his

Siegfried

and

Gˆtterd‰mmerung

, Castorf took us to an alternative historical path for the GDR, an

alternative that turned out not to be so very alternative at all,

(Al)Exander Platz still a commercial, post-socialist wasteland, Wall

Street still failing to burn, here we seem perhaps to have joined the

USSR for an alternative 1930s.

Or have we? Trotskyist hints abound: the rabbit hutch (many thanks to

my friend Sam Goodyear for having pointed out the connection), Mexico

too (‘Partido liberal’, we read on one of many historical and/or

imaginary signs), a film advertisement (in Spanish), starring Alain

Delon. (Hang on, if we are in 1972…?) Even a carnival bird Aljeja,

splendidly sung by Evgeniya Sotnikova, seems both to suggest and to

disavow that possibility. Or are we, was I, confusing him/her – here

most definitely ‘her’ – with the Prisoner with the Eagle, or his eagle?

What might that mean here, whether the confusion or the eagle? Russia

or the USSR, however, it certainly remains, even down to the affinity –

which seems to have been overstated by some – with Aleksandar Deni?’s

Walk¸re set (Azerbaijan, 1942)

. What does a sign for Pepsi Cola in English and Russian tell us? And

what, at the end, does the English poster invitation to travel to the

USSR as a holiday destination mean, not least in such appalling

circumstances? Is it a joke, as is perhaps suggested by the presence of

a Ring crocodile? Stop trying to ascribe meaning to

everything: is that not what, as an imprisoned intellectual, one is

compelled to do? Are we to see the future and will it to work, or

perhaps indict it? Who knows? We shall never make the journey, just

like so many of those prisoners, yet unlike, perhaps, Gorjan?ikov, who

thinks he has something written in his head. Like Dostoevsky, like

Trotsky, like Castorf, like our writer, Alexandr Petrovi? Gorjan?ikov,

we write and rewrite. So too does the action all around, on stage, on

film, seen and unseen; so too, of course, does the orchestra.

Photo credit: Wilfried Hˆsl.

Photo credit: Wilfried Hˆsl.

It is complicated, yes; how can a fragmentary drama with so many

‘characters’ or at least people not be? But it is also visceral,

direct. Violence we see, we feel, whether we like it or not, be it in

the Guard’s sadistic flagellation (a truly nasty Long Long, almost a

match for the still nastier Governor of Christian Rieger) or in the

metal of the steppes’ orchestra. Opera too, even in this most

inhospitable of circumstances, is reborn. If the Wanderer seemed to

have been an inspiration for our noble prisoner’s initial journey to

this camp, Peter Mikul·ö capturing both intelligence and a certain

camouflaged nobility, then it is the Wotan of the second-act Walk¸re monologue who comes to mind in that of äiökov. That is

partly a matter of Bo Skovhus’s searing portrayal, quite the most

powerful performance I have seen and heard from him in a long time. But

everyone involved has played a role in putting these pieces together,

in constructing something from these musico-dramatic shards. ‘A mother

gave birth even to Filka,’ after all – and we know it, because, like

äiökov, he sings, not least in this devilish incarnation from Aleö

Briscein. So too, earlier, do Don Juan (an outstanding Callum Thorpe)

and his pseudo-Leporello (another excellent performance, this time from

Matthew Grills), in a play-within-a-play. That, thanks to Castorf’s

lengthy experience with and rejuvenation of post-dramatic commentary,

seems more of a play-in-itself than I can recall – until, once again,

it does not.

Evgeniya Sotnikova as Aljeja. Photo credit: Wilfried Hˆsl.

Evgeniya Sotnikova as Aljeja. Photo credit: Wilfried Hˆsl.

For, like Don Giovanni, this is redemptive within and

without, or seems to be: as I said, it takes life and drama as they

are. A (post-)religious consciousness is at work here. It also,

perhaps, suggests what they might be, or at least what one day, when

the revolution comes again, the revolution to which we cling no matter

what, we might hope it to be. The noble prisoner leaves, though, so

most likely not. He has used, learned from his experience; so, we

imagine, have we. The carnival of (Russian) death continues. There is a

chink of something uncertain. In the blackest of comedies, we might

even think it light. Humanity even – though are we not all now

post-human(ist) as well as post-dramatic? Who knows, who cares? This

human comedy and tragedy of which we are part rolls on, just as it did

for those CalderÛn-like figures of a reimagined Salzburg World Theatre

in the celebrated post-war Furtw‰ngler Don Giovanni. The final

scene alienates – like Mozart’s. And yet, like that too, it moves (us).

We have experienced something, even if we have not a hope in our living

hell of learning what it may have been. We have, like this Gorjan?ikov,

written a work of sorts in our head. No one will read it or even

remember it, perhaps it would be impossible for anyone to make sense of

its difficult, even nonsensical fragments; yet that spark of

creativity, of art, of that which Marx just as much as Schiller

considered made us human, has flickered. At least we think it did.

Perhaps. Or at least we thought it did. Once. Perhaps. We return, like

Gorjan?ikov, like Trotsky, to watch the post/non-human (non-)drama of

the rabbits in their hutch, caged like us and yet (to the sentimental?)

more free. Perhaps.

Mark Berry

Leoö Jan·?ek: From the House of the Dead

Alexandr Petrovi? Gorjan?ikov: Peter Mikul·ö; Aljeja: Evgeniya

Sotnikova; Luka Kuzmi? (Filka Morozov): Aleö Briscein; Skuratov:

Charles Workman; äiökov: Bo Skovhus; Big Prisoner, Prisoner with the

Eagle: Manuel G¸nther; Little Prisoner, Bitter Prisoner: Tim Kuypers;

Governor: Christian Rieger; Old Prisoner: Ulrich Refl; ?ekunov: Johannes

Kammler; Drunk Prisoner: Galeano Salas; Cook: Boris Pr˝gl; Smith:

Alexander Milev; Pope: Peter Lobert; Prostitute: Niamh O’Sullivan; Don

Juan (Brahmin): Callum Thorpe; Kedrill, Young Prisoner: Matthew Grills;

äapkin, Happy Prisoner: Kevin Conners; ?erevin, Voice from the

Kirghizian Steppes: Dean Power; Guard: Long Long. Director: Frank

Castorf; Set Designs: Aleksandar Deni?; Costumes: Adriana Braga

Peretski; Lighting: Rainer Casper; Video: Andreas Deinert, Jens Crull;

Live Cameras: Andreas Deinert, Stefaniue Katja Nirschl; Live Editing:

Jens Crull; Dramaturgy: Miron Hakenbeck; Revival Director: Martha

M¸nder. Bavarian State Opera Chorus (chorus master: Sˆren

Eckhoff)/Bavarian State Orchestra/Simone Young (conductor).

Nationaltheater, Munich, Monday 30 July 2018.

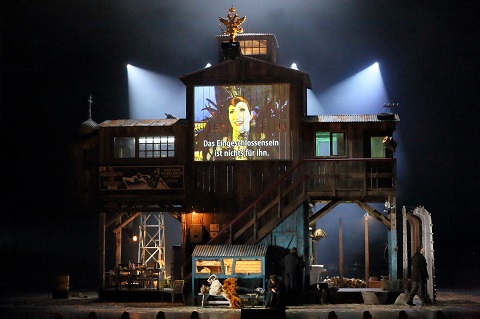

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Munich%20Hofd%20title.jpg

image_description=From the House of the Dead: Munich Opera Festival

product=yes

product_title=From the House of the Dead: Munich Opera Festival

product_by=A review by Mark Berry

product_id=

Photo credit: Wilfried Hˆsl