San Francisco has fielded, masterfully, a giganticized miniaturized version of Gioachino Rossini’s iconic masterwork Il barbiere di Siviglia in a parking lot for hundreds of socially distanced cars.

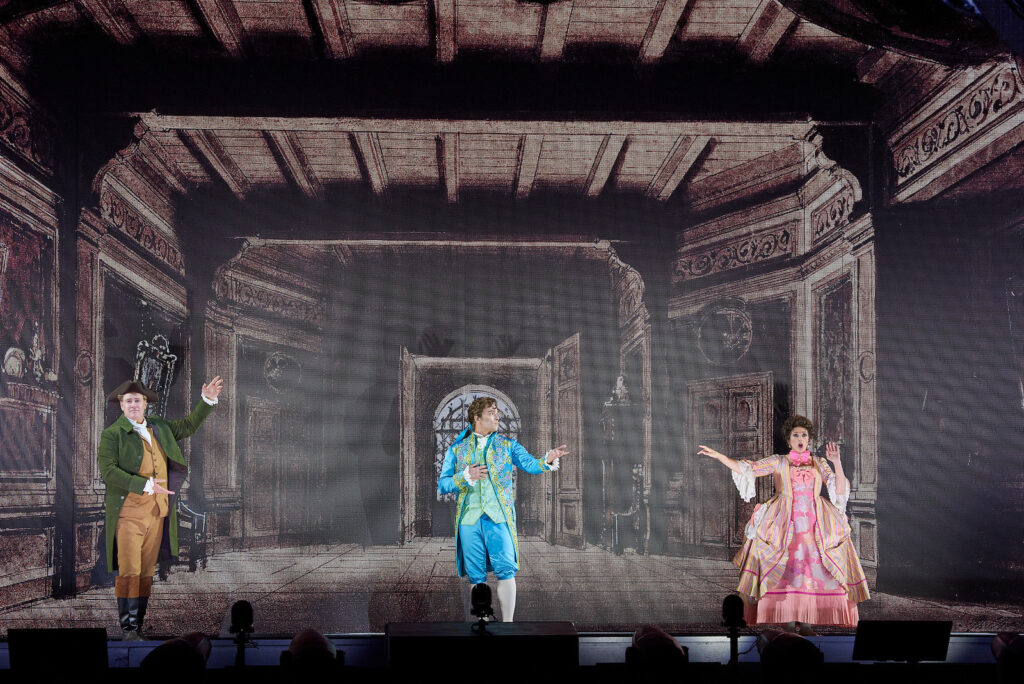

It is jaw-dropping grand opera by all standards, notably the erection of a mammoth steel stage (120 feet wide, 55 feet high — a replica of that erected at the Coachella Festival) and the sheer audacity of concept. Which is to destruct opera buffa (a genre that evolved into its Rossinian perfection from classical Roman comedy over about 1800 years) onto a rock festival landscape, or maybe into a Burning Man operatic wet dream.

The classic Roman comedy plot (youthful innocence prevails over age and greed) was wittily destructed as well. To wit: Rosina was already robustly pregnant with Lindoro’s baby at the get go, thus Bartolo did indeed have a lot to rage about, though he pretended not to notice, or maybe it didn’t matter anyway. Meanwhile Basilio obviously was stricken with Covid, a suspicion we had from the Act I finale where he was distantly placed, un-costumed, on the very edge of the carefully socially distanced principals lined up across the stage (Figaro and Lindoro had earlier marked out a careful six feet with a measuring tape).

With all the superimposed antics (it was a play within a play) not much was left of Rossini’s carefully crafted comic masterpiece. Operatically it was reduced to a ninety minute or so exposition of Barber’s hit tunes and crazed ensembles taken out of order (absolutely no recitative). The show began with “Largo al factotum.” “La calunnia,” sung from Basilio’s obvious quarantine, came near the end. The act II storm and finale were severely curtailed and things came to abrupt conclusion, first in a quite abstracted, formal concert performance of the trio of resolution, “Ah qual colpo”, then in a chorus-less celebration.

At last, the conceptually cacophonized Barbiere spent, came a huge cacophony of automobile horns [motorcycles were not admitted, nor were convertibles] that blasted the huge pleasure had by these hundreds of cars, and the joy of their occupants at the rebirth of a vibrant, alive San Francisco Opera!

But these were not all the glories. Musically and vocally the evening was of accomplishment and interest. The orchestra (seen on the side screens from time to time) was 18 players from the San Francisco Opera Orchestra — single winds and just enough strings to blend their sounds — seated socially distanced [what else] in a tent behind the stage. The lightness and transparency of sound allowed conductor Roderick Cox an alacrity that approached from time to time the famed, elusive Rossini delirium (a huge accomplishment), and always underscored the wit of the production with tempos suited exactly to his singers.

The sound was broadcast into our cars by FM radio. A triumph of the evening was the mixing of the sound, each voice clearly heard in the huge ensembles (simply not possible in an opera house), the superimposition of words was distinct adding a novel dimension to the musicality of these monumental structures. Parked close to the stage I could not see the supertitles projected hugely [too hugely] above the stage, but there was no need, as the quality of the sound transmission and engineered balance with the orchestra allowed the singers’ crystal clear English diction to prevail.

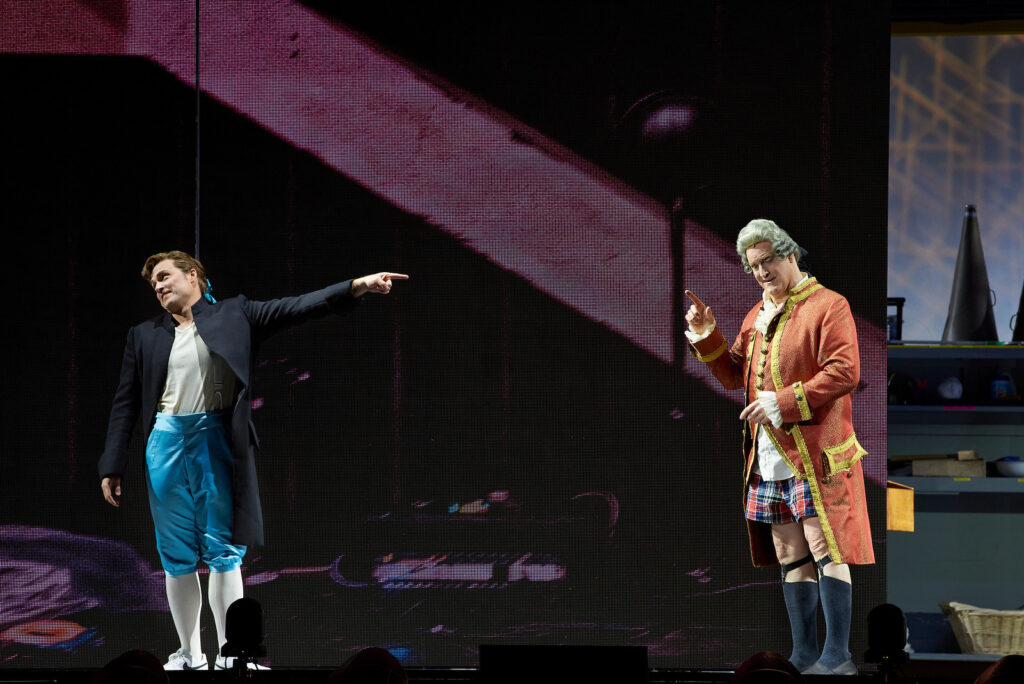

The revised story (putting on an opera mostly) allowed the singers to move from dressing room and rehearsal informality to performance formality. This was most pleasurable in the performances of Daniela Mack (Rosina) and her real-life husband Alek Shrader (Lindoro). Mme. Mack exhibited vocal fireworks aplenty, disguising “una voce poco fa” into an almost unrecognizably new virtuoso aria (it is said that pregnancy enhances vocal production). Mr. Shrader displayed a charming elegance of tone and delivery throughout the considerable acting antics required by the role.

It was easy to appreciate bass Philip Skinner as a brash, brusque Bartolo in the context of this production. He sold his aria “a un doctor della mia sorte” with fine conviction, hitting the wall however when it came to the patter where true Rossinian elegance is required. Bass baritone Lucas Meachem brought his well known, often seen at San Francisco Opera swagger to his well sung Figaro, as did mezzo Catherine Cook in her usual SFO stage persona. Of special note was the Basilio of bass Kenneth Kellogg who delivered his sequestered “la calunnia” in beautiful voice.

The production was masterminded by American stage director Matthew Ozawa, a former assistant director at San Francisco Opera. Unlike most of us, perhaps Mr. Ozawa has been to the Coachella Festival and Burning Man, making his considerable accomplishment with this production maybe explicable. Set and projection designer Alexander V. Nichols conceived an amazing, always evolving visual structure made of two levels divided into multiple rooms, and four huge sliding panels that moved back and forth to provide the screens for a panoply of projected images. Colored asymmetric graphic lines were sometimes used to outline the tiny (by comparison) live performances from their huge video projections that could seen by cars in distant fields (see lead photo, Lucas Meachem as Figaro in his War Memorial Opera House dressing room}.

It is impossible to fathom the myriad of technical requirements of such a production. Whatever challenges there may have been, they were well met. The production was impressively polished on every level.

Michael Milenski

Gioachino Rossini: The Barber of Seville

Figaro: Lucas Meachem; Rosina: Daniela Mack; Almaviva: Alek Shrader; Doctor Bartolo: Philip Skinner; Don Basilio: Kenneth Kellogg; Berta: Catherine Cook; Officer: Will Bryan. Members of the San Francisco Opera Orchestra. Conductor: Roderick Cox; Production: Matthew Ozawa; Set and Projection Designer: Alexander V. Nichols; Costume Designer: Jessica Jahn; Lighting Designer: JAX Messenger. San Francisco Opera at the Marin Civic Center, April 27, 2021.