Though these dates encompass the well known Rossini comedies, both L’inganno felice and La gazza ladra are not comedies but semi-serious operas. La gazzetta, beyond comedy, is just plain farce. Rossini then established himself firmly in Naples where he wrote his great tragedies (though few of today’s opera goers can name more than one or two). Once in Paris he did finally write one last comedy (Le conte Ory in 1828).

Many of us with serious Rossini addictions make an annual pilgrimage to Pesaro where at times we do achieve Rossini nirvana. Such was not the case this August, though there were hints of the great Rossini in L’inganno felice.

The leaky, forlorn Adriatic Arena (home of Pesaro’s famed basketball team) also serves each summer as one of the world’s most interesting and exciting opera houses. This summer the opera installed in this vast space was La gazza ladra or in English The Thieving Magpie, a remount of the 2007 Pesaro production by Damiano Michieletto of recent Covent Garden Guillaume Tell booing fame whose Sigismondo (2010) in Pesaro was soundly booed as well — of course there were vocal protestations at his bows on the opening night of this La gazza ladra.

Stage director Michieletto’s conceit is that Rossini’s opera is a dream fantasy of an adolescent girl. She arranges a few small white tubes on the floor, fashions a sort of swing from some hanging cloth, climbs on and swings about the stage for a while. While it is obvious she is going to be the magpie it is not obvious what the 15 tubes are — cigarettes or tampon cases were overheard intermission interpretations. The tubes were then scenically amplified to provide the huge and only scenic elements.

Principal Gazza ladra singers in ensemble scene, with magpie in center (in white shorts)

Principal Gazza ladra singers in ensemble scene, with magpie in center (in white shorts)

Whatever they might be (for Michieletto they are probably only white tubes) their geometrical arrangements on the stage were Michieletto’s idea of minimalism, as were the costumes, the heroine in a bright green dress the entire evening, the chorus women first in identical brilliant red dresses, then for the execution in identical taupe toned dresses as examples. The chorus was staged in geometric lines or blocks executing geometrically repetitive movements. Five storm troupers made a straight line tableau across the front of the stage displaying their Uzis horizontally over their heads for the execution of the simple peasant girl.

Michieletto is not a musical stage director, insisting that his adolescent magpie-girl intrude, clumsily choreographed, among the singers at the very moments it was possible that Rossini lyricism might take flight. La gazza ladra is mature Rossini, and that means that there is a big cast and abundant ensembles of magnificent musical architecture. This director is oblivious of these structures, placing his five, six or seven singers (and chorus) in arbitrary geometric patterns instead of allowing musical imperatives to determine how, when and where the components move. The famed crescendo of intensities of these fabulous ensembles were therefore intentionally thwarted.

The Rossini Festival has engaged Mr. Michieletto to stage a new La donna del lago for next summer. Go figure.

La gazza ladra is a semi-seria opera — a servant girl of a tenant farmer will marry the farmer’s son but not before it is determined who stole the silver spoon. Meanwhile the servant girl is assumed to have been the thief and has been condemned to death. It is absolute farce endowed with powerful emotional moments that require important musical involvement — its obvious dramaturgical and musical challenges are daunting.

The musical direction of this avowed Rossini masterpiece was entrusted to veteran conductor Donato Renzetti. Mo. Renzetti’s big Rossini period (in Pesaro and elsewhere) was in the early 1980’s. There has been much refinement in the musical understanding of Rossini in the last 30 years that has well surpassed the slow and heavy realization that this maestro imposes. It may well have comfortably accommodated the needs and expectations of the singers of previous generations but it does not support current musical practice. This was evidenced by repeated musical misunderstandings of the orchestra players and some of the singers, i.e. they felt and expected a celerity that was intentionally and forcefully squashed.

Alex Esposito as Fernando, Nino Machaidze as Ninetta

Alex Esposito as Fernando, Nino Machaidze as Ninetta

The role of the servant girl Ninetta was given to Georgian soprano Nino Machaidze. This artist, much beloved by Los Angeles audiences (Gounod’s Juliet as well as Traviata and Boheme) was the perfect, unrepentant Fiorella in L.A Opera’s production of Il turco in Italia, her hard-edged, brilliant coloratura dramatically convincing. Mme. Machaidze does not possess a sweet voice nor does she project a sweet personality that could embody the simple Ninetta. She is all diva business, and she does it very well, but these attributes do not make her a Rossini artist.

There was one fine Rossini artist in the cast, Alex Esposito who sang Ninetta’s father Fernando Villabella. This esteemed bass exudes character and executes thrilling coloratura. Pesaro audiences are famous for extended applause given well performed arias (or scenes). Mr. Esposito’s second act aria was the sole recipient of such appreciation for the entire four hour duration of the performance.

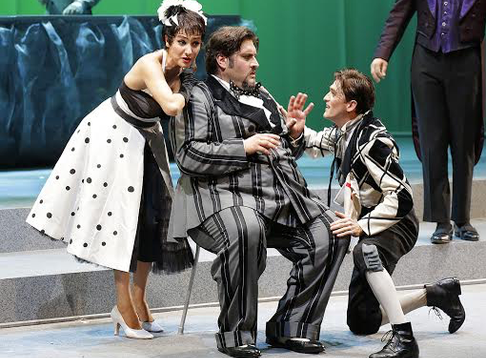

Principals singers of La gazzetta

Principals singers of La gazzetta

La gazzetta or in English The Newspaper was on stage at the 800 seat, horseshoe Teatro Rossini the second night (of the second cycle). This opera was a contractual obligation for Napoli’s Teatro dei Fiorentini (FYI it is now a bingo palace) where audiences loved to be entertained. Rossini lifted some of La gazzetta’s major pieces from his masterwork Il turco in Italia (1814), and composed fine new material as well that found its way a few months later into his masterwork La Cenerentola.

La gazzetta is not a masterwork. A simple enough story (albeit three pages of synopsis needed): a silly father places an ad in the Gazette of Paris offering his daughter in marriage. She however loves the innkeeper. It is a three hour mess that finally gets cleared up at a costume party. As the libretto is based on a play by famed 18th century playwright Carlo Goldoni there is a lot of lively repartee that leaves us non-Italians (there are a lot of us and we come from around the globe) at a disadvantage — plus the supertitles are way above the stage and in 18th century Italian.

None the less there was a lot to look at on the stage, too much, but the story was easy to follow. We just missed the Goldoni wit that we knew was there and way above us. Rossini is performance art, this piece dominated by an electric performance by dead ringer Rossini look-alike Nicola Alaimo (a Metropolitan Opera Falstaff as well as a famed Guillaume Tell) as Don Pomponio, the silly father.

JosÈ Maria lo Monaco as Madama La Rose, Nicola Alaimo as Don Pomponio, Ernesto Lama as Tommasino

JosÈ Maria lo Monaco as Madama La Rose, Nicola Alaimo as Don Pomponio, Ernesto Lama as Tommasino

Stage director Marco Carniti gave Don Pomponio a side-kick servant mime he named Tommasino who seconded Don Pomponio’s decisions, argued with them, insisted that Don Pomponio’s wishes be carried out, and suffered Don Pomponio’s frustrations by repeated beatings. Neopolitan actor Ernesta Lama however was not a mute mime as he could not help himself from speaking out from time to time. It was pure comic delight. Stage director Carniti gave this physical theater performer much activity, and it was thoroughly musical, his physical intrusions into the arias and ensembles fully consistent with Rossini’s musical architecture (unlike the arbitrary Magpie intrusions in La gazza ladra).

Marco Carniti and his designer Manuela Gasperoni created a stage box fully enclosed by translucent plastic strips that easily absorbed projected colored light when not serving as a silhouette surface. Much of the mise en scËne was in black and white, the costumes by Maria Filippi (a Franco Zeffirelli collaborator as well) were primarily in black and white but sometimes with bright color accents. This high design concept supported endless production numbers (like 1950’s American film musicals), including highly choreographed movement of the abstracted set pieces and much movement by four fine supernumeraries.

It was all too much for the simplistic wit of farce, and at the same time it was very well done and musically solid.

Hasmik Torosyan as Lisetta, Vito Priante as Filippo

Hasmik Torosyan as Lisetta, Vito Priante as Filippo

The singing was of good level, notably the silly father’s daughter Lisetta, sung by young Armenian soprano Hasmik Torosyan who last summer was a participant in the festival’s young artists program, the Accademia Rossiniana. The innkeeper Filippo was sung by Vito Priante who with Nicola Alaimo were the two fully accomplished performers of the evening, Mr. Priante offering delightful coloratura dressed as a Turkish suitor in the masquerade.

Conductor Enrique Mazzola provided an unobtrusive, fully idiomatic orchestral basis, but the wit and charm of Rossini’s orchestrations were overwhelmed by the production.

Principal singers of L’inganno felice

Principal singers of L’inganno felice

A Graham Vick production is always news, even moreso because this L’inganno felice was the revival of his 1994 Pesaro production for the Teatro Rossini, staged before he had become one of the world’s most admired and adventurous stage directors. In recent years he has reappeared at Pesaro with MosÈ in Egitto (2011) and Guillaume Tell (2013) — both mise en scËnes are masterpieces.

L’inganno felice is a simple, sentimental farce, the oft-used situation of a foundling baby, but here beautiful young woman, having been washed up on a shore. Here the shore was near a remote mine somewhere. A kindly old miner protects her and engineers a safe return to her beloved husband by tricking the very evil suitor she had rejected.

Vick and his designer Richard Hudson (most famous for The Lion King [1988], but on the other hand famous for this winter’s Graham Vick production of Gˆtterd‰mmerung at Palermo’s Teatro Massimo) imagined one grand diminution of light over the one and one half hours of the opera’s only act. The production’s original lighting designer Matthew Richardson returned to once again effect this spectacular light show — high noon becomes late afternoon then early evening, finally night falls to give cover for the deception. Meanwhile a miniature steamship traverses the far away, endless horizon for the duration of the action.

The set is an enormous curved white cyclorama with some Japanese looking gray splotches as clouds. There was a hole for the mine, a bench on the right indicating a house just offstage. When Nisa’s long lost husband, Bertrando happens to happen by he erects a tent on the other side of the stage. The stage floor is in cinematic detail, a realistic slope complete with struggling shrubs.

However Bertrando and his soldiers are straight out of nineteenth century operetta, Bertrando with grandiose epaulettes. Greek tenor Vassilis Kavayas, a recent Rossini Academician, brought ultimate snap and sparkle to his character as did his snappy soldiers to their marching entrances and exits.

Giulio Mastrototaro as Ormondo (blue uniform), Vassilis Kavayas as Bertrando, Mariangela Sicilia as Isabella, Carlo Lepore as Tarabotto, plus soldiers and supernumeraries

Giulio Mastrototaro as Ormondo (blue uniform), Vassilis Kavayas as Bertrando, Mariangela Sicilia as Isabella, Carlo Lepore as Tarabotto, plus soldiers and supernumeraries

The realistically costumed rustic miner Tarabotto was sung by veteran basso-buffo Carlo Lepore whose accomplished presence anchored the young cast. Also simply costumed in rags was Nisa, sung by ingenue soprano Mariangela Sicilia, a recent Rossini Academician as well. She began the evening with a splendidly sung contemplation of a tiny necklace pendent portrait of her long lost husband. Most of her remaining music required sustained singing but as the evening progressed her intonation seriously deteriorated.

Young Italian baritone Davide Luciano brought seriously snappy buffo to his role, Batone, an ardent, if not too bright sergeant. He had much to sing, and did a convincing and charmingly energetic performance that made you wish his coloratura was just a bit sharper. As it was the high point of the evening was the extended duet Batone sings with the miner Tarabotto where Tarabotto induces him into the deception. This duet and Alex Esposito’s aria “Eterni Dei, che sento!” in La gazza ladra were the two high points of all three operas of the festival)

With his eclectic set and his spotty cast Graham Vick’s palate had a bit of everything to work with. It was all masterfully laid out in low key, absolutely unpretentious terms, allowing us to enjoy all these wonderful performances without critical prejudice — though may we believe that back in 1994 perhaps the Vick production had considerable artistic prÈtention.

Great Rossini begins in the pit. The conductor was a thirty-four year old Russian, Denis Vlasenko, still another of the evening’s former Rossini Academicians. While Pesaro’s Orchestra Sinfonica G. Rossini lacks the finesse of the Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna (in the pit for La gazza ladra and La gazzetta) this young maestro still was able to create an estimable Rossini elation from time to time, the Rossini high that brings us back to Pesaro year after year.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information

La gazza ladra: Vingradito: Simone Alberghini; Lucia: Teresa Iervolino; Giannetto: RenÈ Barbera; Ninetta: Nino Machaidze; Fernando Villabella: Alex Esposito; Gottardo: Marko Mimica; Pippo: Lena Belkina; Isacco: Matteo Macchioni; Antonio: Alessandro Luciano; Giorgio: Riccardo Fioratti; Ernesto/Il Pretore: Claudio Levantino; Una Gazza (mute): Sandhya Nagaraja. Orchestra e Coro del Teatro Comunale di Bologna. Conductor: Donato Renzetti; Stage director: Damiano Michieletto; Scenery: Paolo Fantin; Costumes: Carla Teti; Lighting: Alessandro Carletti. Adriatic Arena, Pesaro, Italy, August 13, 2015.

La gazzetta: Don Pomponio Storione: Nicola Alaimo; Lisetta: Hasmik Torosyan; Filippo:†Vito Priante; Doralice: Raffaella Lupinacci; Anselmo:†Dario Shikhmiri; Alberto: Maxim Mironov; Madama La Rose: JosË Maria Lo Monaco; Mons˘ Traversen: Andrea Vincenzo Bonsignore; Tommasino (mute): Ernesto Lama. Orchestra e Coro del Teatro Comunale di Bologna. Conductor: Enrique Mazzola; Stage director: Marco Carniti; Scenery: Manuela Gasperoni; Costumes: Maria Filippi; Lighting: Fabio Rossi. Teatro Rossini, Pesaro, Italy, August 14, 2015.

L’ingannno felice: Mariangela Sicilia; Bertrando: Vassilis Kavayas; Ormondo: Giulio Mastrototaro; Tarabotto: Carlo Lepore; Batone: Davide Luciano. Orchestra Sinfonica G. Rossini. Conductor: Denis Vlasenko; Stage director: Graham Vick; Scenery and Costumes: Richard Hudson. Lighting: Matthew Richardson. Teatro Rossini, Pesaro, Italy, August 15, 2015.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Gazza_Pesaro1.png

product=yes

product_title=Rossini Opera Festival, 2015

product_by=A review by Michael Milenski

product_id=Above: Sandhya Nagaraja as the magpie, Teresa Herovlino as Lucia in La gazza Ladra

All photos copyright Studio Amati Bacciardi, courtesy of the Rossini Opera Festival.