This new production by Roland Schwab, conducted by Markus Poschner was given an ecstatic welcome by the acolytes of Wagner’s revered Festspielhaus. There were, in fact, occasional, very occasional moments of sublimity.

Stage director Schwab undertook the daunting task of creating two simultaneous worlds, one of primal human desires (love, i.e. yearning, and destruction, i.e. death — transcendental realities), the other world surrounds us, it is the life we see and feel as we exist day to day.

Director Schwab chose to place Wagner’s treatise on love and death on a cruise ship, or maybe it was a spacecraft, either vessel though might be confused with a nickelodeon (a machine that lights up when you put a coin in).

But then, all mostly said and done, Isolde having begun her “Liebestod,” a decrepit ancient couple (modern dress) entered and separated, circling slowly to then reunite at the final moment of Isolde’s ecstasy of separation. Hearsay has it that during the ecstasies of the Act II love duet there was a contemporary dress teenage couple making-out on the upper deck of the ship, though not in my sight lines. At the final bows these two couples were joined by a couple of children who evidently had been strategically deployed somewhere at some point.

But mostly, obviously, the staging was of Wagner’s transcendental world as musically revised by conductor Markus Poschner. The staging dialectic imagined by Herr Schwab evidently encouraged the maestro to introduce a dialectical discussion of his own, contrasting the metaphysical magic of Wagner’s musical flow to the nuts and bolts of its construction, evidencing the colors of its smaller motives and inner lines, slowing the flow so that every rhythmic complexity was apparent, that every individual word was distinctly formed, every musical comment was clearly understood.

Such plodding had its ups and downs. If the Act III Tristan monologue sometimes assumed an illuminating clarity, its emotional climaxes were compromised, dissolving into a conglomeration of over-loud sounds. Isolde’s Act I discourses descended into angry exclamations, exacerbated by her childishly slapping the wall and stamping her feet from time to time. Most damaging, this musical dialectic resulted in clumsy singing that came from the outsized voices of the Tristan and Isolde, particularly troublesome in the Act II duets.

The setting, the work of Herr Schwab’s usual design collaborator Piero Vinciguerra, was a spectacular ship of some sort. There was a virtual body of water in the center of this full stage vessel, placed below an upper deck that had an ocular opening through which a sky was apparent. Both the pool and sky were sentient, i.e. the enthusiasms of Tristan and Isolde were visually manifest by means of digitally formed images apparent within its confines, shapes and colors that got hyper from time to time. Plus the several circles that comprised the donut shaped spaceship were outlined with hidden lights that went berserk at appropriate moments.

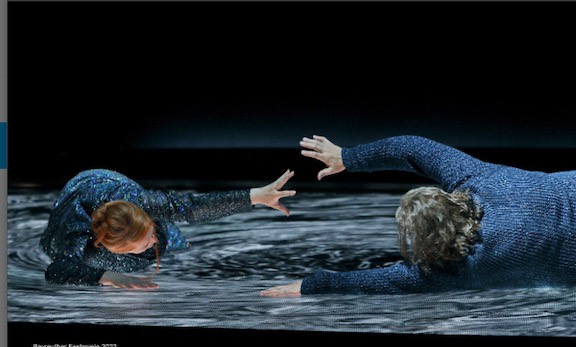

In the first act the pool was a swimming pool, blue until it turned boiling red. After the love potion was drunk the lovers walked onto the surface of the pool, now a magical space where they remained over/within the virtual pool’s various, quite remarkable manifestations to come. In fact there were moments of visual sublimity, the lovers pulled into a vortex, the lovers lost in a galaxy of stars, the dying Tristan in a sea of candles. All this spectacle was Herr Schwab’s representation of Wagner’s transcendental world.

Near the end, when Isolde arrives at Tristan’s castle on Brittany’s rocky coast, the spell has been somehow broken, the world is no longer transcendent, it is an every day world. Thus Isolde cannot walk across the pool, now a pond or maybe an ocean, that separates her from Tristan. It is a real life barrier. She sings her “Liebestod” (and it was beautifully sung) to Wagner’s world of dream and destruction. Life goes on.

This magical world created by Messieurs Schwab and Vinciguerra was indeed magical, requiring its inhabitants to move in magical ways, i.e. with some balletic grace at the very least. Unfortunately neither British soprano Catherine Foster nor American tenor Stephen Gould are or could have been dancers, resulting in clumsy movements that ran counter to the expressive intentions of the production. Both singers are formidable artists, of formidable voice who were not suited to this difficult to realize, high concept production.

The King Marke of German bass Georg Zeppenfeld was well sung indeed, and well acted within the framework of the production. Kurvenal, well sung by German baritone Markus Eiche, had the onerous task to circle Tristan’s death pond for the entire duration of the soliloquies, a task accomplished with patient aplomb. Brangäne was sung in very beautiful voice by Russian mezzzo Ekaterina Gubanova, and gracefully enacted as well.

Tristan’s friend Melot was strangely cast. Icelandic baritone Olafur Sigurdarson had the age one expects for King Marke (Mr, Zeppenfeld did not). Melot wielded an onstage lighting instrument (of which there were always a few — reminding us that Wagner’s opera is theater and not reality) that he focused on Tristan for the duration of the Act II King Marke soliloquy. He then stood aside as a huge chandelier of abstract blades slowly descended through the ocular opening to wound, symbolically, Tristan (see lead photo).

It was a long and difficult evening at the Wagner shrine.

Michael Milenski

Tristan und Isolde, Festspielhaus, Bayreuth, August 12, 2022. All photos copyright Enrico Nawrath courtesy of the Bayreuth Festival