Among the most performed titles in the repertory, it was the 30th performance of Verdi’s Il trovatore in this 2016 production by Barcelona’s chic theater collective La Fura dels Baus, and the 57th performance of Bizet’s Carmen in this 2017 production by chic stage director, Calixto Bieito, originally of Barcelona’s Teatre Romea.

At the premiere of a production an opera company generally tries to assemble a cast that is integral to the production, and to itself, i.e. singers appropriate to the role as envisioned by the production, and singers of similar professional levels — though there are sometimes contretemps, and that’s a fun part of the opera game. Then come the revivals of productions when casting is less carefully curated, sometimes it is assembled around star singers, other times the casting may seem to be somewhat random in an opera company’s need to balance its programming with popular titles.

Thus our interests in a revival production may be in the singers who find themselves cast, in the musical values imposed by a particular conductor, and how singers and conductor fit into the original concept of a production.

Director Bieito has had Carmen productions in European theaters since 1999. His take on Carmen is rather tame compared to his Barcelona Wozzeck, or his Basel From the House of the Dead, though in his 2014 Bilbao Carmen there was fellatio, pissing, nudity, gang rape, child abuse and unbridled brutality. Mercedes was Lilas Pastia’s middle-aged wife, and yes, Don Jose was really annoyed by an insistent Micaëla who sang her pretty song and then gave Carmen the “up-yours.”

Mr. Bieito is now artistic director of the Bilbao opera.

The 2016 edition for San Francisco was sanitized in much the same way as this 2017 Paris edition as performed last week at the Opéra Bastille. There was none of the above. It can be noted as well that in Paris there were six older cars that pulled on stage to create the gritty Act III gypsy camp, in San Francisco there were three grand, vintage Mercedes, while in Bilbao there were eight delightfully dilapidated, grand old wrecks.

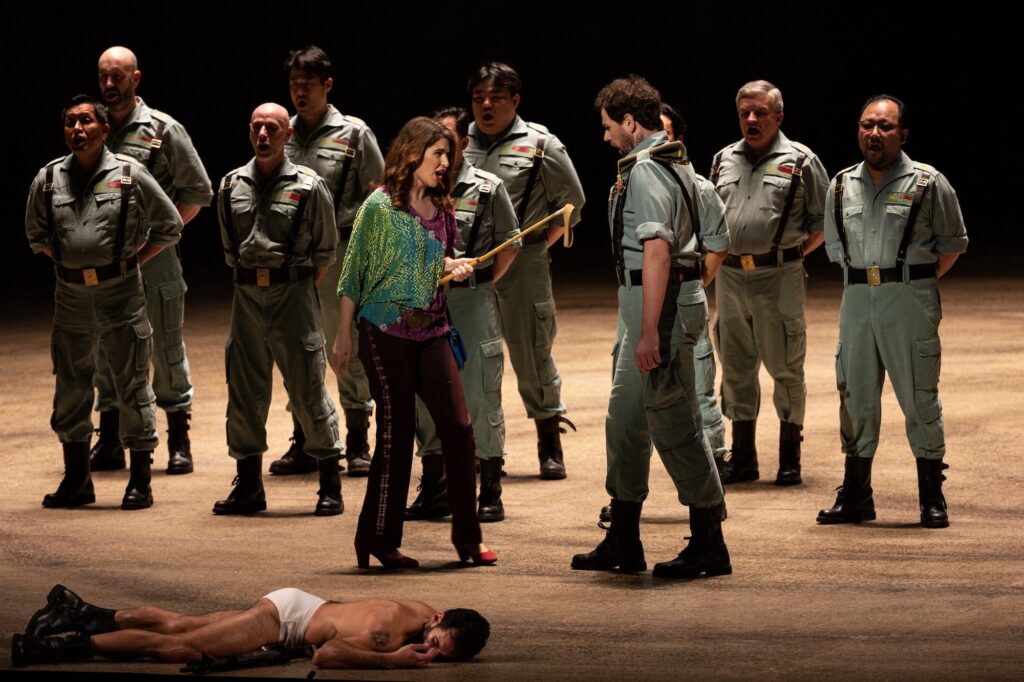

What all three editions did share, however, was the circle image made on an otherwise bare stage. In Act I a circle was delimited by a semi-nude soldier circling the stage for much of the act, jogging, punishingly, until he dropped from exhaustion. In Act IV Lilas Pastia laid a broad chalk circle that we knew was a bull ring. Thus, at the end, Jose drags the slain Carmen from this ring, as the dead bull is dragged out of the corrida. Note lead photo.

It was oh so brutal in Bilbao where there is real corrida, so much less so in San Francisco and Paris.

Given that the Bieito production is little more than a bare stage with some circles and a few old cars, its effect relies largely on its actors. Back in Bilbao the first Carmen withdrew because of illness, the second Carmen could do all the performances except the one I saw when Carmen was the understudy/cover, and distinctly not a Carmen. The Jose was plausible, The Escamillo was long past being able to jump onto the roof of a car for his knife fight with Jose, though he did anyway, somehow. The Micaela, and the gypsies were superbly cast as true characters who fortunately could sing fairly well. They made the show.

San Francisco Opera cast fresh voiced, innocent young singers, though more or less age appropriate to the characters of the Merimée tragedy on which Bizet’s opera is based. These excellent, upwardly mobile young artists had spent their formative years struggling in voice lessons and coaching sessions and not groveling in gypsy camps. It was indeed a great pleasure to see and hear such well-prepared young artists. The Bieito production however needed so much more.

Which brings us to Paris just now. Clearly none of the artists had passed much of their lives in gypsy camps, though the Carmen, French mezzo-soprano Clémentine Margaine, surely has spent some time on the streets getting from her Carmen debut in 2012 at the Detaches Open Berlin, to her celebrated Carmens at the Opéra de Paris and at the New York’s Met both in 2017. Endowed with a sizable, well-used, rich voice she exemplified just now nearly any adjective attributable to the Carmen ideal — sexy, dangerous, seductive, calculating, fiery, hot, cold, etc.

With this major Carmen figure a Jose of vocal stature was unavoidable. For this winter series of performances it has been veteran Maltese tenor Joseph Calleja. While able to negotiate the vocal treacheries of the role, Mr. Calleja does not have the temperament nor a freshness of voice to create a real Jose — though he did muster sufficient bravura to hold the stage with Mlle. Margin’s bonafide Bieito personage. Barely. He too was well past the point of gracefully jumping onto the hood of a car for his knife fight with Escamillo, though he did manage to get upon it, somehow.

Of artistic merit were the Micaela of Australian soprano Nicole Car and the Escamillo of Italian bass Ildebrando D’Arcangelo. Both artists are quintessentially Mozartian, neither with the histrionic range to confront a true Bieito personage. They gave us cleanly sung, exemplary vocal performances, and great pleasure indeed, Mlle. Car a model of virtue, purity and innocence, Mr. D’Arcangelo, agile, virile and smugly smooth.

True to expectations at a major theater this Carmen arrived at a musical perfection, conductor Fabien Gabel imposing strict and brisk tempos. That the excellent children’s chorus stayed exactly on the maestro’s quick beat during the staging complexities of the huge act one chorus scene was the triumph of the evening.

Opéra Bastille, Paris, France. January 28, 2023

Le Trouvère

Though the Opéra national de Paris billed Verdi’s Il trovatore as Le Trouvère just now, it was not Verdi’s French version of the opera at the Opéra Bastille — there was no ballet. It had been, however, Le Trouvère (in French) that debuted this Verdi opera at the Opéra de Paris back in 1857 — with ballet.

Il trovatore, with Rigoletto and La traviata are the stalwart pillars of the Verdi canon, and the foundation of any opera company’s repertory. Of this triumvirate, Trovatore is the most difficult to pull off. Given the absurd implausibility of its story and its flow of magnificent set piece after magnificent set piece, it demands major singers and a determined Verdi conductor. The production itself never seems to matter all that much though a bit of color is always welcome.

This Paris production is by the stage director Alex Ollé tied together with La Fura dels Baus though it is unclear what the Barcelona theater collective has had to do with it, other than that the set and costume designers both have tenuous ties to the collective according to their program bios.

La Fura dels Baus is famed for its staging of the opening of the 1998 Barcelona Olympic Games, for street theater, and operatically for the creation and use of unusual settings — in my experience there has been a huge, nude woman crouching on all fours for a 2008 production of Le Grand Macabre at English National Opera, and a massive wall of plastic water bottles for a 2014 production of Le Siège de Corinthe) at the Rossini Opera Festival in Pesaro.

In Paris (though first it was in Amsterdam) the set is a grid of massive brown square pillars multiplied by a mirrored backdrop. They rose and descended in and out of squares cut into the brown floor, like pistons, though these pillars were pulled, threateningly, way up into the stage void by steel cables from time to time. One can greatly admire the precision of the installation of such a stage machine. The pillars when submerged had crosses placed on them from time to time to indicate tombs of war dead, given the costumes recalled World War I, including gas masks. At other times those square holes in the floor became that war’s infamous, but now chorister inhabited, trenches.

Stage director Ollé’s apology in the program booklet likens the set to Berlin’s Holocaust Memorial in the grids of stelae they share, though he says that there is no intended correspondence, the connection only that war in general has innocent victims.

Be that as it may we were left with the singers, the generic, quite responsible conducting of Carlo Rizzi, and this indeed impressive, huge war machine on the stage.

The Ferrando was sung by Italian bel canto bass Roberto Tagliavini. He had the opera’s first blockbuster aria “Di due figli vivea padre beato.” He delivered it in true bel canto style, executing its florid lines with exciting precision, the hiccuping opening lines, then the repeated, descending scales, awakened our anticipation for Azucena’s equally florid, equally exotic song “Stride la vamps” that was soon to come. This famed gypsy was sung by Romanian mezzo Judit Kutasi, but she missed the dramatic punch of her opening aria — the horror of her mother’s death and the sacrifice of her child — not yet having found her voice. She did pull through her tense scene with Manrico with certain vocal aplomb, though she never embodied the tragic stature of this tormented woman.

Italian soprano Anna Pirozzi was the Leonora. While she once may have had fame as Lady Macbeth and Abagail (Nabucco) she brought neither resplendent voice to Leonora, nor a dramatic urgency to this innocent, love-smitten young woman. Her opening piece “Tacea la notte placida” was dry voiced, abandoning all possibility of displaying the raptures of love in its soaring lines. The villain of the opera, though his only crime is his infatuation with Leonora, is the Count de Luna, an early example of the Verdi baritone — a voice of heroic color, imposing volume and the stamina to traverse an upwardly extended register. This role was taken by Canadian baritone Étienne Dupuis who had no difficulty at all singing the role, missing however was the vocal heft and noble color to make this quintessential Verdi villain a dramatic force in Verdi’s opera.

The cast was dominated by Manrico — the trouvère, Leonora’s lover, the counts brother, and the adopted son of Azucena. The role was sung by Azerbaijan born, Italian formed tenor Yusif Eyvazov, the only true Verdian of the evening. Often paired with soprano Anna Netrebko in major dramatic roles around the world, it was revealing to encounter him solo, not part of this imposing team. A tenor voice of pleasurable heft if not distinct color he has assumed the persona of a primo tenore assoluto, and this alone added a needed excitement to his stylistically well-informed performance. Mr. Eyvazov’s third act “Ah sì, ben mio, coll’essere” was resplendent, the following magnificent cabaletta “Di quella pira l’orrendo foco” with its high C’s brought the house down. Mr. Eyvazov is a singer, not an actor.

The eighty singers of the mighty Opéra national de Paris chorus made a huge impression when all together. When in the smaller ensembles that occur throughout the opera they were amusingly manipulated by the reflective surround of the Fura dels Baus set, making it hard to know who and what was where when. Or why.

Michael Milenski

Opéra Bastille, Paris, France. January 27, 2023