A few weeks ago it was one act per night in Los Angeles, in Paris just now it is all three acts at once, as it had been back in 2005, the original year of this awesome production in Paris (its premiere in Los Angeles was in 2004). The production has since been seen also in Toronto and Madrid

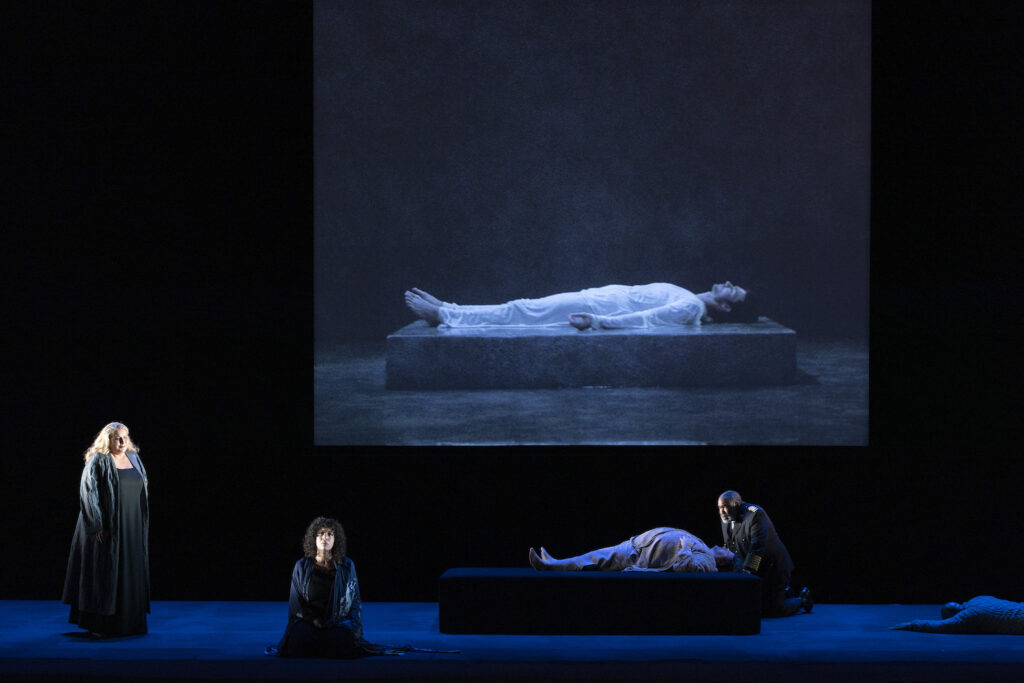

It is nothing more than a blank stage, an ottoman, a massive screen for video projection, plus a huge orchestra that was on the Disney Hall stage in LA, but in the Opéra Bastille pit in Paris.

The creation of by-now legendary artistic forces, stage director Peter Sellars and video artist Bill Viola, plus the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s super star conductor Gustavo Dudamel (back in 2005 the conductor was the LA Phil’s Esa-Pekka Salonen), it was an integration of diverse forces that achieved a balanced perfection — costumed actors in few but decisive movements and positions, a video stream comprised of few, always transforming images, and the score of Wagner’s great masterpiece held in the sway of its few, dominant moods.

The opera’s overture, left un-staged, was performed as a concert piece, conductor Dudamel provoking a static tension that resolved into the overture’s shattering climaxes. This process began again in Act I, though it grew into a cataclysmic confrontation of the opera’s philosophic forces. The Act II prelude established a primal, relentless minimalist beat that endured through the negotiations of light and night, the aspirational coupling, and then through the agonized outpourings of the deceived patriarch. Act III’s monologue was again in stasis, with sudden, nervous eruptions that Dudamel magically transformed into the opera’s ultimate, magnificent transfiguration, a musical feat that dwarfed Isolde’s Liebestod prayer.

Say what you may about the Opéra Bastille [seating is only slightly more comfortable than Bayreuth’s benches], its acoustic is superb. The wide stage offers a wide pit, it’s ample depth easily accommodated the 92 players of the production’s excellent orchestra. This full scale Wagnerian ensemble achieved a breath of tone that enveloped the theater’s 2745 spectators in sonic grandeur.

Stage director Peter Sellars exploited this acoustical immediacy by positioning the back stage Act I sailors chorus somewhere in a nearby public area so that they would fill the theater with loud, immediate and threatening sound. At the act’s conclusion Sellars illuminated the auditorium itself where we soon discovered King Marke standing in an aisle among us. We were indeed smack in the midst of the complexities confronting Tristan and Isolde. It was compounded in Act II with the hunting horns (fourteen brass players) again in a public area summoning us to return to our seats (à la Bayreuth), and then Brangäne’s lovely prayer was sung from the high balconies. Act III’s shepherd’s voice and horn, again arose from the far reaches of the balconies, fully enveloping us in the darkness of Tristan’s delirium.

Sellars staged his actors in formal, often frozen positions, sometimes in an area defined by a square of color, notably Kurwenal’s Act III entreaties. Movement was formalistic, notably Isolde’s Act I sharp-armed, feigned assassination of Tristan. It was wrenching to witness Marke, supine on the floor at Tristan’s feet, recount the complexities of the Tristan betrayal.

Sellars’ specific storytelling was at floor level, beneath a very large but not overwhelming screen on which appeared the ever evolving video images created by Bill Viola, based on his reading of Wagner’s poem. This visual storytelling interfaced loosely both with Sellars own storytelling, and with Dudamel’s exposition of Wagner’s musical flow, completing the elements of this canny, savvy post modern take on Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk (unifying all forms of art via theater).

The Bill Viola œuvre in general explores nature’s basic elements — fire, water, wilderness (candles, oceans, forests) — in both threatening and restorative guises, in rhythms and transformations that slow, stop and sometimes reverse time. These are brought to bear, easily and quite naturally, onto the Wagner masterpiece. As well Bill Viola contemplates the human form in his video art, reveling in the motions of a sculptural plasticity. In Act II, notably, heroic figures appear as surrogates of Tristan and Isolde, though here there was not the idealization of form as in classical sculpture, instead the male and female forms were shown in a photographic detail that revealed them as a man and a woman (note lead photo).

This humanity manifested itself in the very specific casting, especially in choosing a raw voiced Isolde, a voice that would not/could not adapt itself to that of an idealized, mythological Irish princess, though possessed of a basic musicality that made her a very special post modern Wagnerian heroine. In Isolde’s most triumphant moment, her Liebestod, this simply clad singer stood beneath the huge screen and sang her prayer with convincing sincerity. On the screen a female form in white diaphanous drapery rose magically and majestically through oceans of water to disappear, finally, into the maestro’s eternity of love.

At the Act I bows (the surprising act bows recalled the production’s original three night format in LA), the Isolde, Mary Elizabeth Williams, was met with loud booing. As the evening progressed we did come to understand that Mlle. Williams was quite possessed by Isolde, that she was in fact Isolde. A very determined Isolde. At the final bows — and she had the final solo bow! — she was greeted with a huge ovation.

Tristan was beautifully rendered in fully heroic operatic terms by Swedish heldentenor Michael Weinius, fulfilling as well the broad humanity of director Sellars’ casting ethos. The same may be said of the beautifully voiced, heroic Brangäne of German dramatic soprano Okka von der Damerau. Of heroic physique and voice was the Kurwenal of American bass baritone Ryan Speedo Green (Jake in the Metropolitan Opera’s Porgy and Bess), whose urgings to Tristan took on, in the new-age humanity of this production, the unlikely tone of berating him. American bass Eric Owen (Porgy in the Met’s Porgy and Bess) was a King Marke of remarkably beautiful voice. Wounded by Tristan’s actions his soliloquy poured out as a heartbreaking lament.

The cast was completed by the Melot of British tenor Neal Cooper, a facilitator of the story rather than one of its actors, and the fine voices of its helmsman sung by Tomasz Kumiega and shepherd sung by Maciej Kwaśnikowski.

Costumes were designed by Martin Pakledinax, the lighting design was by James F. Ingalls, a longtime Sellars collaborator.

Michael Milenski

All photos copyright Elisa Harberer, courtesy of the Opéra de Paris.