Polish pianist and composer AndrÈ Tchaikowsky, born in November 1935, had

experienced the ghettos of Warsaw as a child; he was also a homosexual. One

imagines that the discriminatory divisions and brutal biases of The Merchant of Venice struck a personal chord; that,

paradoxically, he empathised with both the experience of the despised

Jewish moneylender, Shylock, and with the latter’s nemesis, the refined

Venetian, Antonio, whose melancholy has oft been accredited to his

frustrated homosexual love for Bassanio – a love which other Venetians in

the play mock: ‘You look not well, signor Antonio’, smirks the garrulous

Gratiano.

Martin Wˆlfel (Antonio) and Mark Le Brocq (Bassiano). Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Martin Wˆlfel (Antonio) and Mark Le Brocq (Bassiano). Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Tchaikowsky’s opera was completed in 1978. He offered it to ENO, when the

company was under Lord Harewood’s directorship and David Pountney was

artistic director, but in 1982 it was rejected and Tchaikowsky, seriously

ill with cancer, died shortly afterwards at the age of 46. It remained

unperformed until Pountney, by then artistic director of the Bregenz

Festival in Austria, commissioned performances, directed by Keith Warner,

for the 2013 festival. WNO’s performances of this production in Cardiff in

September last year brought the opera to the UK for the first time.

In Shakespeare’s day, Venice was considered an eclectic model of democratic

republicanism, international trade, maritime prowess, Renaissance art and,

as in Ben Jonson’s Volpone, corruption and vice. But, Shakespeare

largely ignores these stereotypes and focuses on the city’s cultural

divisions and conflicts (a pattern repeated in Othello). The ‘City

of Love’, he suggests, is intoxicated by hatred.

WNO cast. Photo credit: Johan Persson.

WNO cast. Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Keith Warner’s production emphasises not just the prevailing persecution

and prejudice but also the motives which fuel them: in this case,

mercantile ruthlessness and envy. Ashley Martin-Davis’ handsome designs

take us to the underbelly of Venice’s leisured glamour: its bank vaults.

There are none of the magnificent ‘argosies with portly sail’ – emblems of

the trading wealth that paid for the city’s opulent piazzas, buildings and

art – that dominate the conversation at the start of Shakespeare’s play.

Venice’s commerce depended upon the finance made available by Jewish

usurers, and so the Jews were ‘tolerated’ not out of humanitarianism but

because of mercantile necessity.

Warner and Martin-Davis take us directly into the city’s counting houses:

sturdy strong-boxes form the very fabric of Shylock’s house. The set’s

mobile walls rotate slickly, spinning us through a world of ceaseless

commercial transaction. The action is updated to the Edwardian era – a

period during which the cosmopolitan Jewish elite, from the highest

echelons of the likes of the Rothschilds to the middle-class financiers,

seemed largely integrated into London society, until the start of WW1

released previously repressed hostility. Warner and Martin-Davis thus

ignore the gondoliers and visual riches of the Rialto, just as

Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice ignores the local colour and

opulence, to focus on the Venetians’ self-justifying persecution of the

stereotyped ‘alien’.

John O’Brien’s libretto largely follows Shakespeare’s plot and imports much

text – too much? – verbatim. There are some unexpected omissions, though.

The absence of Bassanio’s description of Portia – ‘a lady richly left;/ And

she is fair, and, fairer than that word,/ Of wondrous virtues: sometimes

from her eyes/ I did receive fair speechless messages’ – with its

alliterative dreaminess, deprives the spendthrift’s request for a loan of

its romantic validation: after all, he is asking his homosexual admirer for

money that the latter does not have so that he can pursue his female

beloved. Then, when Shylock commands Jessica to lock the doors of his house

in his absence, the usurer’s detestation of music – of the ‘vile squealing

pf the wry-necked fife’, the ‘shallow foppery’ that shall not enter his

‘sober house’ – is excised; it seems strange to omit an opportunity to exploit the text for

characterisation, given the operatic context – after all, Shakespeare’s

villains are never lovers of music. But, then, I suppose something has to

go.

Tchaikowsky employs a lyrical vocal idiom which often has much grace – as

in Portia’s ‘quality of mercy’ monologue – and rhetorical impact, as in

Shylock’s vociferous self-vindication, ‘I am a Jew. Hath not a Jew eyes?’,

which is moved, with dramatic effectiveness, from the Act 3 street scene in

which Shylock spits his exculpation at Solanio and Salarino to the

court-room denouement, where his audience is the Venetian state itself.

But, the arioso lines often drift and overall the opera feels too

wordy. One wishes that O’Brien had been more adventurous, re-ordering and

revising in order to create ‘anew’, in the manner of a Boito, as there is a

danger that the music becomes simply illustration – an enabling medium for

the presentation of the play, rather than a work in its own right. Even

Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream – which was similarly faithful

to the original, adding just one line of ‘explanatory’ text (‘compelling thee to marry with Demetrius’) and

in which the lovers’ music can suffer from the same plaint – has the

unsettling eeriness of Oberon’s countertenor magic, the elevation of

‘Bottom’s Dream’ and, not least, the wonders of Britten’s score to suggest

new meanings.

Musically, here, there is a predominant debt to Berg and, while not

particularly memorable, the score serves the tenser dramatic moments

adequately. However, the languorous lyricism of Belmont evades Tchaikowsky.

Both Lorenzo’s final-act eulogy to music and the entire second Act – which

feels like an extended scherzo, in which the divertissements are

supplemented by an on-stage (here, side-box) Renaissance consort of two

recorders, oboe d’amore, oboe da caccia, two bassoons, lute, tabor and

harpsichord – lack the requisite ‘poetry’.

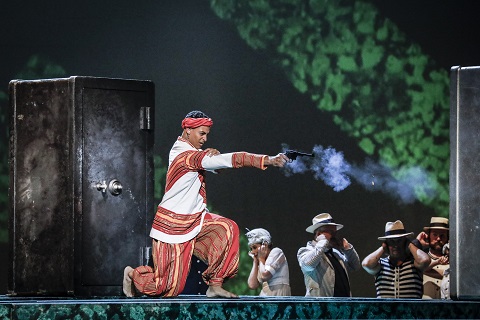

Wade Lewin (Prince of Morocco). Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Wade Lewin (Prince of Morocco). Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Warner offers a contrast to the dark Venetian drama of the opening act and

stages the Act 2 Belmont scenes within a box-hedge maze, a bird’s-eye view

of which is artfully relayed on a video back-drop. The easy luxury, sense

of sexual freedom (at one point Portia pins Nerissa down in what seems a

lesbian embrace), frequent interpolation of musical allusion and set-piece

(‘Tell Me Where Is Fancy Bred?’ is delivered by a Dietrich-style diva in

white top hat and tails) and the maze itself, put me in mind of Kenneth

Branagh’s 1993 film of Much Ado About Nothing. But, the flippancy

feels excessive: the caskets are held in three cumbersome safes, reminding

us of the ugly, mercenary motivation behind the suitors’ quests, but the

riddle scenes are hyperbolic – the gun-toting Moroccan prince leaps

acrobatically and resorts to an outsize detonator to gain entry into the

gold casket – and disproportionate, disrupting the dramatic flow.

Lionel Friend conducts with attentiveness to the details of the score – the

orchestra is large – and does a good job at keeping stage and pit in

balance and coordination. The instrumental interlude following the

court-room scene was beautifully played, a poignant representation of

Shylock’s defeat and, Warner suggests, death: for Shylock seems to succumb

fatally to his shame and humiliation, his ghost rising during the moonlit

meeting of Lorenzo and Jessica, to haunt his daughter’s betrothment and

betrayal.

African American baritone Lester Lynch is cast as Shylock, his race adding

to the alienation signalled by his gabardine and skull-cap amid the

prevailing Edwardian urbanity. Lynch’s voice glows with pride and hatred,

while the contortions of the tuba, bass clarinet and counter-bassoon convey

his self-destructive bitterness. There seems little to redeem him: in the

trial scene, he pulls on his rubber gloves like an amateur surgeon, eager

for his ‘pound of flesh’, deaf to the warnings of the Duke of Venice –

nobly sung by MiklÛs SebestyÈn – that ‘victory’ will bring Shylock only

vilification.

Lauren Michelle’s Jessica may toss her father’s treasure chests through the

casements with overly enthusiastic gusto into the sheets held below by

Lorenzo’s Christian friends, but she must fight her own battles to overcome

prejudice. Michelle coped well with the high melismatic lines which,

crystalline, rose above the scornful reception she meets at Belmont and

deepened our sympathy still further.

Sarah Castle was superb as Portia. Her strong diction allowed Portia’s

words to penetrate to the back of the stalls, giving the feisty

proto-feminist further stature, while her phrasing was stylish. Its

elegance was equalled by Mark Le Brocq whose high-lying lines conveyed all

of Bassanio’s levity and heedlessness. Verena Gunz’s animated Nerissa and

David Stout’s tactless Gratiano made a well-matched pair. Only Martin

Wˆlffel disappointed: Tchaikowsky’s decision to cast Antonio as a

counter-tenor (presumably to emphasise his homosexuality – Antonio

surprises Bassanio with an impetuous kiss when the latter embarks for

Belmont to woo Portia) may be questionable, but by any measure Wˆlffel

lacked power and definition, and the English text was indistinguishable.

Verena Gunz (Nerissa), David Stout (Gratiano), Bruce Sledge (Lorenzo) and Sarah Castle (Portia). Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Verena Gunz (Nerissa), David Stout (Gratiano), Bruce Sledge (Lorenzo) and Sarah Castle (Portia). Photo credit: Johan Persson.

Warner’s production opens and closes with an image of Antonio on the

psychiatrist’s couch. The final gesture – Antonio hurls an object at

Shylock’s ghost, silhouetted against the moon – is presumably designed to

suggest that the therapy isn’t working, unable to overcome the depth and perpetuation of

hatred, but if so it seems redundant. More importantly, it subverts or at

least alters the balance of the ending of Shakespeare’s romantic comedy, in

which love and loyalty defeat malice and cruelty. That said, Warner does

consistently emphasise the darker aspects of Shakespeare’s tale and at the

close of this production the scales of justice are still crookedly weighted

with intolerance and bigotry.

Claire Seymour

AndrÈ Tchaikowsky:

The Merchant of Venice

Co-production of the Bregenzer Festspiele, Austria, the Adam Mickiewicz

Institute as part of the Polska Music programme & Teatr Wielki, Warsaw/

Shylock – Lester Lynch, Antonio – Martin Wˆlfel, Lorenzo – Bruce Sledge,

The Duke of Venice – MiklÛs SebestyÈn, Bassanio – Mark Le Brocq, Solanio –

Gary Griffiths, Salerio – Simon Thorpe, Gratiano – David Stout, Jessica –

Lauren Michelle, Portia – Sarah Castle, Nerissa – Verena Gunz, Prince of

Aragon/Freud – Juliusz Kubiak, Prince of Morocco – Wade Lewin, A Boy –

Fiona Harrison-Wolfe, Woman one – Amanda Baldwin, Woman two – Helen

Jarmany; Director – Keith Warner, Conductor – Lionel Friend, Designer –

Ashley Martin-Davis, Original Lighting Designer – Davy Cunningham (realised

by Ian Jones), Movement Director – Michael Barry, Associate Director – Amy

Lane, WNO Orchestra and Chorus (Chorus Master – Robert Pagett).

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Wednesday 19th July

2017.

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Martin%20Wolfel%20%28Antonio%29%20and%20Lester%20Lynch%20%28Shylock%29-%20WNO%27s%20the%20Merchant%20of%20Venice-%20photo%20credit%20Johan%20Persson-%202708.jpg

image_description=The Merchant of Venice, WNO at the Royal Opera House

product=yes

product_title=The Merchant of Venice, WNO at the Royal Opera House

product_by=A review by Claire Seymour

product_id=Above: Martin Wˆlfel (Antonio) and Lester Lynch (Shylock)

Photo credit: Johan Persson